Forget BMI. Doctors want to use new BRI system to measure how ’round’ you are – here’s how it works

Experts recommend a new way to determine your health risks based on your body size — and it has nothing to do with weight.

The measurement, called the body roundness index (BRI), is calculated based on a person’s height and waist circumference.

Researchers have found that people with the curviest body types are a whopping 163 percent more likely to develop heart disease than their peers with slimmer waists.

They say BRI may be a more accurate predictor of heart disease and death than using body mass index (BMI).

The body roundness index calculates a person’s body size by including waist circumference and height, unlike the body mass index which uses height and weight. This could give researchers a better idea of fat distribution in the body, and could be more useful in doctors’ offices, experts say.

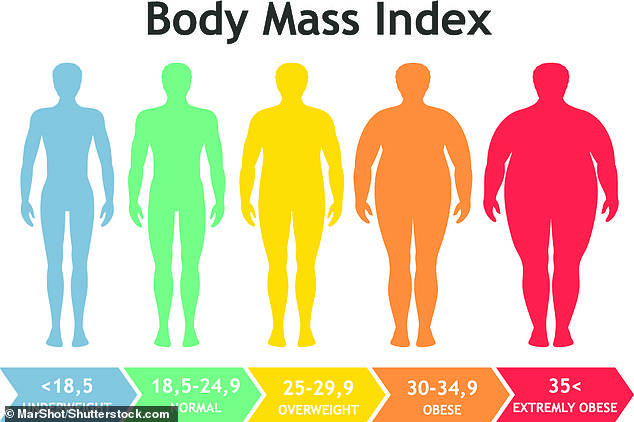

BMI is a commonly used, but recently controversial, measurement that uses a person’s height and weight to determine whether this is the case underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese or extremely obese.

There has been a lot of criticism of BMI as a metric, especially because it was developed by studying wealthy white men, who have a different average mass than other demographic groups.

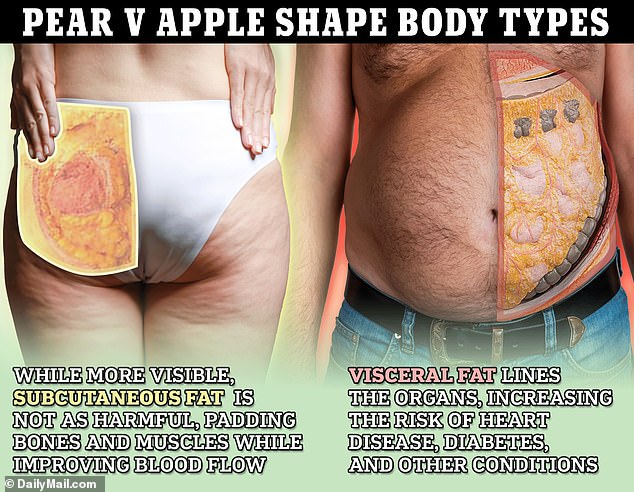

Additionally, studies have shown that where your fat is located on your body can have a greater impact on your health than the total amount of fat you carry.

BMI cannot take into account where fat is located on the body.

Fat located around your abdomen and vital organs has been linked to an increased risk of diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease.

But fat stored just under the skin, in areas such as the legs and buttocks, has not been linked to any health risks.

Dr. Wenquan Niu, a BRI researcher at the Capital Institute of Pediatrics in Beijing, said The New York TimesBelly fat is “like a silent killer that lurks in our bodies and can sneak up on a person over the years with few noticeable symptoms, especially among apparently thin people:”

The research of Dr. Niu and his colleague were placed in the Journal of the American Medical Association and it evaluated how well BRI predicted mortality by looking at data from more than 320,900 U.S. adults over 20 years.

They divided the participants into five groups based on their height, weight and waist circumference. Group five had the roundest bodies, group three was average and group one had the leanest bodies.

They excluded the influence of other factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, income, tobacco and alcohol use, family history and diabetes.

Even after this was taken into account, and looking at the number of deaths in each group, they found that those in the roundest group were 49 percent more likely to have died than those in the average group.

Subcutaneous fat is more visible outside the body, fills the outer muscle layers just beneath the skin, and is not associated with certain health conditions. Visceral fat, which lies deep between the organs, is more dangerous but less noticeable.

Interestingly, people in groups one and four were 25 percent more likely to die than the average group.

Similarly, a study from Nanjing Medical University published in the newspaper shows Journal of the American Heart Association found that having a consistently high BRI over a six-year period increased the risk of cardiovascular disease – such as heart attack and stroke – by as much as 163 percent.

Study author Dr Yun Qian said this could be because obesity and high belly fat have been linked to a number of conditions that make a person more likely to develop heart disease, such as high blood pressure.

Dr. Qian added, “BRI measurements could potentially be used as a predictive factor for the incidence of cardiovascular disease.”

Body Mass Index (BMI) places people into one of five categories based solely on their height and weight. Critics say this metric is inaccurate and can’t take into account things like fat distribution and muscle mass – suggesting BRI might be better

In recent years, the tide has started to turn against BMI.

In 2023, the American Medical Association recommended against its widespread use in doctors’ offices.

The organization said there are “problems with using BMI as a measure because of its historical harms, its use for racial exclusion, and because BMI is primarily based on data collected from previous generations of non-Hispanic white populations.”

Critics say this is because the tool was built solely using data from wealthy white men. Yet it is applied to measure people of all demographics, which critics say makes it inaccurate.

Carrie Dennett, a registered dietitian nutritionist with a clinic in the Pacific Northwest, wrote for the Seattle Times: ‘As a measure of individual health, BMI has always been nonsense.’

They point out that BMI also cannot distinguish between weight, muscle and fat. That’s why you get misleading results, such as highly muscular athletes being classified as obese, Ms. Dennett said.

Still, BRI isn’t perfect, she said: “BRI is “better” than BMI, but it still perpetuates weight-focused health care.”