Groovy gibbons! Hilarious video reveals how apes dance just like humans – with moves ‘like a cross between robot and vogueing’

A hilarious video reminiscent of a cross between Peter Crouch and Michael Jackson: the moment a cheeky gibbon performs a dance for a captivated audience.

The female, filmed at a shelter in Ninh Binh, Vietnam, stands with her back turned as she falls and moves in a dramatic manner described as a “cross between a robot dance and vogueing.”

Scientists watched seven gibbons perform the intricate dance, consisting of jerky sideways and upward movements that wouldn’t look out of place in a 1970s New York nightclub.

Not only does the dance resemble that of humans, but the gibbons also perform it for humans – probably to get attention when they are hungry.

It is already known that primates, besides humans, can dance – some even while listening to music – but few are as remarkably stylized as this one.

With their backs to humans, the Nomascus gibbon performs an intricate dance consisting of jerky sideways and upward movements that would not be out of place in a 1970s New York nightclub.

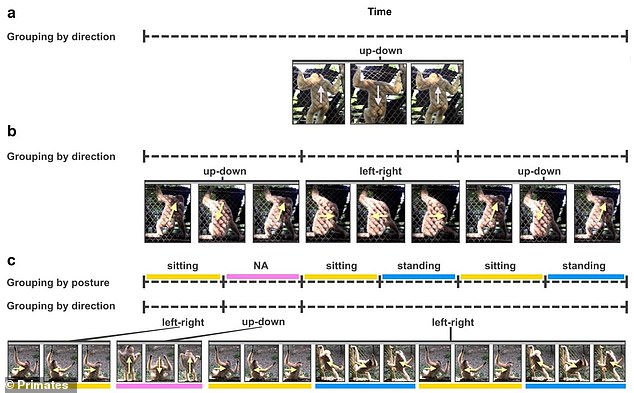

This image illustrates the various movements in the Nomascus dances, from up-and-down movements and left-right movements nestling in alternating sitting and standing postures

According to the study’s author, Professor Pritty Patel-Grosz from the University of Oslo, it “looks like a cross between robot dancing and vogueing.”

‘The general structure of the dance was the same across species, in that it always consisted of a temporary stiffening of the body accompanied by jerking movements of the limbs, which superficially resembled a human ‘robot dance’,’ she told MailOnline.

‘However, the complexity and duration of the dances varied greatly between individuals.’

The scientists observed seven gibbons from four species dancing: the northern buff-cheeked gibbon, the northern white-cheeked gibbon, the southern white-cheeked gibbon and the yellow-cheeked gibbon.

All four species are found in Vietnam and Laos in Southeast Asia – although these particular creatures have been filmed in European and Australian zoos and the Endangered Primate Rescue Centre in Vietnam.

Researchers define the dance as “a sudden, temporary stiffening of the body accompanied by rhythmic, often repetitive, trembling bodily movements,” although the dance was performed without music.

Interestingly, only adult females of this species performed the dance, not males.

In the wild, the dance is thought to be a sexually suggestive signal to attract a male – a “predictive signal to elicit copulation,” as the researchers call it.

The team says: ‘Our results show that dances in Nomascus represent a common and intentional form of visual communication restricted to sexually mature females’

The scientists observed four species performing the dance: the northern buff-cheeked gibbon, the northern white-cheeked gibbon, the southern white-cheeked gibbon and the yellow-cheeked gibbon.

But in captivity – as is the case with these gibbons – the dance has a wider range of applications.

The researchers noted that the females also performed the dance toward humans, usually with their backs to the viewer.

So they think the dance takes place in preparation for mealtime, or simply as part of social interaction with other people.

These observations are unusual, as animal dances are usually performed for mating.

According to experts, these gibbons are officially dancing because their movements are “deliberate, rhythmic, and non-mechanically effective,” meaning they serve no practical function.

For example, walking is a ‘mechanically effective’ movement because it has a practical function: getting from one place to another.

The photo shows a female of the white-cheeked gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys). This species is mainly found in Laos, Vietnam and southern China (archive photo)

“We propose that the gibbons’ dances likely evolved from less elaborate rhythmic, predictive signals,” the team concludes.

The observations are further detailed in a preprint article which will soon be published in the journal Primates.

Of course, there are many other animals that dance, including many birds, but they usually do it to impress their partner.

Grebes (elegant water birds native to Britain) perform a ‘water ballet’ – a serene dance where the birds synchronize their heads and move up and down in unison.

In Central and South America, red-capped manakins perform a so-called ‘moon walk’ along branches during their mating ritual.

And male mudskippers – fish that can survive out of water – make high jumps, twist their tails and arch their bodies in an attempt to blind a female.

Researchers at Kyoto University in Japan have recorded captive primate chips that moved their bodies and heads back and forth and even clapped when they listened to piano music.