Archaeologists unlock 3,000-year-old secrets about creation of universe and monsters after deciphering oldest known map of the world

Researchers have finally deciphered a Babylonian tablet believed to be the world’s oldest map.

Created between 2,600 and 2,900 years ago, the Imago Mundi has offered researchers a unique insight into the beliefs and practices of this ancient civilization.

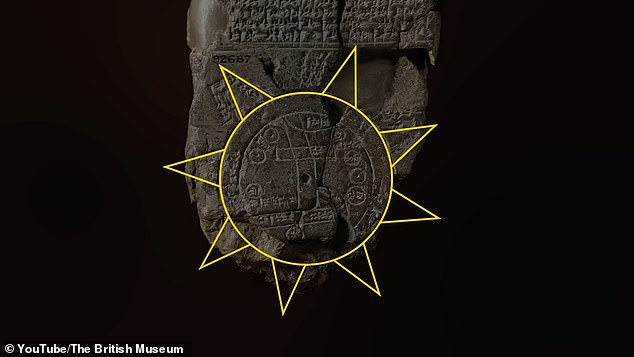

The Babylonian tablet contains a circular map with text fragments in cuneiform, an ancient writing system that used wedge-shaped symbols. This text describes the early creation of the world.

The map depicted Mesopotamia, or the land ‘between the rivers’, a historical region in the Middle East that was thought at the time to comprise the entire ‘known world’.

The map on the tablet also confirmed their belief in the mighty God of Creation, Marduk, and in mythical creatures and monsters such as the scorpion-man and Anzu, the lion-headed bird.

The Imago Mundi, also called the Babylonian world map, (pictured) was discovered in 1882 by the famous archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam in Sippar, an ancient Babylonian city in present-day Iraq.

Dr. Irving Finkel (pictured) revealed the cuneiform writing on the back of the Babylonian map, revealing the ancient people’s belief in a higher power

The Imago Mundi was created at a time when the Babylonian Empire was a world leader in architecture, culture, mathematics, and early scientific achievements.

They were known for developing an advanced number system for mathematics and were the first to create a functional theory of the planets, using geometry, among other things, to track Jupiter.

The map was originally discovered in 1882 by the famous archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam in Sippar, an ancient Babylonian city in present-day Iraq.

Although Rassam discovered the tablet nearly 150 years ago, the Imago Mundi remained in a box of finds from his excavations until it was rediscovered in Iraq 29 years ago.

It is currently on display at the British Museum in London.

Since the discovery of the tablet, researchers at the British Museum have gained greater insight into the Neo-Babylonian Empire’s belief in mystical beings and its dominance over the region.

At the bottom center of the map lies Mesopotamia, but what is especially special are the two circles that enclose the city.

“The double ring is very important because it has cuneiform writing in it that says ‘bitter river’ and this water was believed to surround the known world,” Dr Irving Finkel, an expert at the British Museum, said in an interview with The British Museum. YouTube video.

Researchers confirmed that the circle on the stone surrounding Mesopotamia supported the Babylonians’ belief that this region was the center of the world. However, they understood that Mesopotamia was part of a larger area.

Two circles surrounded Mesopotamia on the map and were designated the Bitter River to indicate that the Babylonians believed they were the only nation in the world

Various regions and areas were marked in cuneiform on the map, which Finkel explained in a YouTube video

There was another river, the Euphrates, which crossed ancient Mesopotamia from north to south and which on the tablet connected to the Bitter River.

“This is a very important water ring,” Finkel said, “because it meant to the Babylonians that by the sixth century they had a sense of the boundaries of the world in which they lived.”

The map contains cuneiform inscriptions with the name of the city or tribe that lived there, including Assyria, Der, and Urartu.

“So this circular diagram encapsulates the entire known world in which people lived, thrived, and died,” Finkel said.

But the map contains more than just the location of Mesopotamian territories: triangles in the right corner of the tablet formed a magical and mysterious element for the Babylonians.

Some people suspect the triangles are islands, but Finkel said in the video that they are “almost certainly mountains.”

In the cuneiform text, the area is described as a place ‘where the sun is not seen’. This makes sense, since the mountains hid the sun from view.

“Their location, combined with the cuneiform above them, gave further support to the theory. The idea is that if you go across the water, you see these protruding, pointy things above the horizon. These are remote areas, far beyond the boundaries of the known world.”

The triangles at the edge of the circle represented mountains and the Babylonian belief that the sun disappeared there

Part of the cuneiform text also refers to the Babylonians’ belief that mythical creatures lived in various regions of the country, including a winged horse, a sea serpent, a scorpion-man, and a bull-man.

The British Museum reported that the text on the tablet ‘seems to be a description of the inhabitants, divine, human, animal, or monstrous, of the regions beyond the earth, whether the eight ‘regions’ or the ‘Bitter River’ or perhaps the underworld or the waters of the underworld.’

Because the tablet is fragmented in places, the full text could not be deciphered. According to the British Museum, it does mention ‘ruined cities … which Marduk keeps an eye on.’

According to Mesopotamian mythology, Marduk was the god of creation and the patron god of Babylon. He was also worshipped as the god of justice, compassion, healing, and magic.

According to Finkel, the ancient Babylonian map “has given us tremendous insight into many aspects of Mesopotamian thought.”

He added that ‘it’s also a triumphant demonstration of what happens when you have a very small, totally uninformative and useless fragment of deadly dull text that no one can understand and you merge it with something in the collection that’s much larger, and a whole new adventure begins again!’