Revealed: How Boeing’s faulty Starliner could crash into the ISS in worst case scenario

Boeing’s failed Starliner spacecraft finally begins its journey home today after three months docked at the International Space Station (ISS).

However, experts are concerned about the small chance that Starliner could malfunction again and possibly end up in the ISS.

“The chances that the Starliner could hit the ISS if all the thrusters failed are extremely small,” former US space system commander Rudy Ridolfi told DailyMail.com.

“This is like NASCAR for NASA, some people just look at the crash,” Ridolfi added.

Due to technical problems with the Starliner, including failure of the thrusters, the crew has been stuck on the ISS for the past three months.

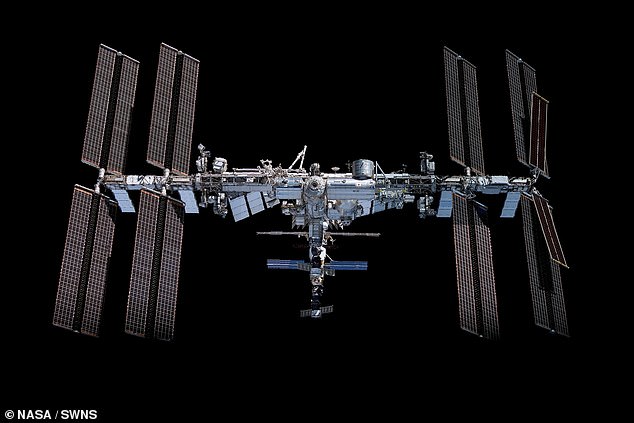

Starliner will attempt to autonomously undock from the ISS today. Experts say there is a small chance that problems with the thruster could cause the craft to crash into the space station.

NASA officials decided it was too risky to bring astronauts Sunita Williams and Barry Wilmore home in the disabled spacecraft. They will remain on the ISS until next year, so Starliner is returning to Earth unmanned today.

Shortly after 6:00 p.m. ET today, Starliner will autonomously undock from the ISS and begin a six-hour flight back to Earth.

The spacecraft launched on June 5, carrying Williams and Wilmore to the ISS.

By the time the spacecraft reached the ISS, five of the reaction control system’s 28 thrusters had failed.

As a result, Starliner’s first attempt to dock with the space station was aborted. However, the spacecraft eventually docked successfully, and Williams and Wilmore safely boarded the ISS.

When asked if the propulsion issues have been resolved, “I would say no,” Harvard University astronomer and astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell told DailyMail.com.

Although NASA and Boeing have identified overheating as a likely cause of the problems, “they still don’t fully understand why the boosters are behaving the way they are. That means they can’t say for sure that they won’t behave erratically again,” he said.

“That said, I expect things to go well tonight,” he continued. But in a very unlikely worst-case scenario, thruster problems during undocking could cause Starliner to collide with the ISS.

For example, if one of the thrusters doesn’t stop firing when commanded to do so, “it could cause the Starliner to collide with another part of the space station,” he said.

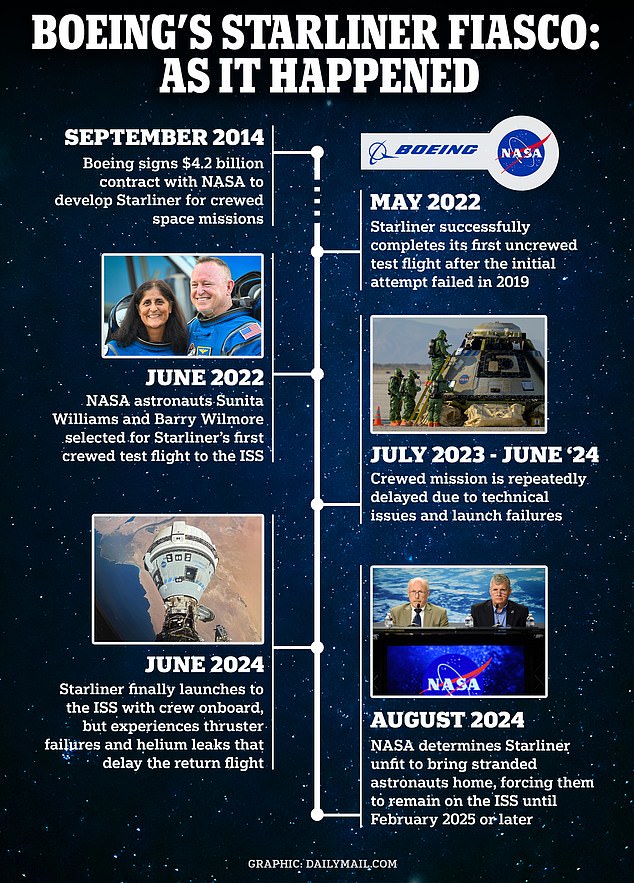

A complete timeline of Boeing’s Starliner program, from the singing of their giant contact to the incident that left two astronauts stranded aboard the ISS.

Crashes like this have happened before. In 1997, a Russian space station was damaged when a cargo spacecraft missed its docking port and crashed into one of the station’s modules.

The collision left a hole in the space station “and the astronauts had to quickly close the hatches on the module before all the air was removed from the entire space station,” McDowell said.

“That was very, very scary. So that’s what you want to avoid,” he added.

Additionally, there is a chance that the Starliner could become stuck on the way to the ISS and eventually crash if more than a certain number of its thrusters fail, McDowell previously told Company Insider.

“That could happen, but it would have to be very specific solutions that fail,” Ridolfi wrote in a statement to DailyMail.com.

“There are five sets of thrusters and if they can still run the spacecraft, the sets of thrusters can take over from the sets that are no longer working,” he continued.

If the booster fails and the Starliner comes on a collision course with the ISS, a crash will not happen immediately, Ridolfi said.

That’s because although the two objects will be close to each other, they will be in slightly different orbits, he explained.

“The US Space Force (USSF) is going to do what it calls a ‘conjunction analysis’ to determine when the two objects might collide,” he said, adding that this could be a problem about every 90 minutes, as both objects have completed an orbit around the sun.

But the ISS also has its own thrusters that it can use to avoid a collision, which happens several times a year, Ridolfi said.

However, “it is difficult to move the ISS, especially because it is a pig and moves very slowly,” he added.

The ISS is equipped with its own thrusters, which it can use to avoid a collision. This happens several times a year.

In addition, mission control “keeps a finger on the pulse. If one of the thrusters behaves erratically, the rocket is shut down and control is taken over by a backup thruster,” McDowell said.

But even if Starliner manages to successfully undock from the ISS, it is not completely out of the danger zone. After undocking, the spacecraft must re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere.

“At that point, the thrusters really have to be working well because they’re steering the ship while the main engines are running. It’s important to have the main engines running in the right direction,” McDowell said.

“For example, the worst-case scenario is that you lose the propulsion system completely and you can’t control the spacecraft as it leaves Earth orbit and burns up,” he added.

In that case, the Starliner capsule would return to Earth at the wrong angle and speed, causing it to burn up or temporarily stall in orbit and then return uncontrolled some time later, he explained.

The problem with an uncontrolled de-orbit burn is that Starliner has heat shields to help it survive re-entry. Therefore, “you can imagine pieces of this thing surviving all the way to the surface,” McDowell said.

Problems with Starliner’s booster likely played a role in NASA’s decision not to take astronauts Sunita Williams (front left) and Barry Wilmore (front right) home on the spacecraft.

“And if you were really unlucky, it could happen in a place where a lot of people live. And then you could have a repeat of the incident we had earlier this year where a poor man saw pieces of spacecraft go through the roof of his house,” he continued.

But that scenario is highly unlikely. McDowell thinks it’s more likely that problems with the booster could cause Starliner to burn up over the Pacific Ocean instead of landing at White Sands Space Harbor, New Mexico, as intended.

If the Starliner’s thrusters fail during re-entry, there is little mission control can do to fix the problem, McDowell said.

If problems arise from the start, mission control can shut everything down, keep Starliner in space for another day and try again the next day, he explained.

“But once you get going, and things go wrong there, you’re already on a trajectory where you’re going to hit the atmosphere one way or another. So you just have to hope that everything stays good,” he said.

The risks associated with possible problems with the booster during Starliner separation and re-entry likely played a role in NASA’s decision not to bring Williams and Wilmore home with the spacecraft.

The space agency announced its decision at a press conference on August 24.

Williams and Wilmore will remain on the ISS until at least February 2025, when SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft will return them to Earth.

During another press conference on Wednesday, NASA officials said they have been working to mitigate any risk to the ISS during Starliner’s undocking and that tests of the spacecraft’s thrusters have shown that they are working properly.