Rudi Vata Interview: The streets where I lived and played were made of dirt. This is where I had to learn to become a winner…

The voice is measured, but there can be no doubt about its power.

‘The streets where I lived and played were dirt. There were no cars, only bicycles. We were boys from five to ten years old.

Here I had to learn to be a winner. I had to build my mentality against bigger guys. The competition for me starts when you learn to walk.

‘I wanted to win. I lost so many times. I cried with anger when that happened. But losing is also a part of life.

We played barefoot. I had cuts and bruises, wounds in my leg, but I don’t remember ever complaining. I broke my leg when I was six and then I broke my arm. But I always wanted to play football in the streets.’

Rudi Vata (left) is praised by Celtic team-mate Paul McStay

Vata celebrates Celtic’s victory in the 1994-95 Scottish Cup Final at Airdrie

This was the reality of Shkoder, Albania, in the 1970s. The speaker is Rudi Vata, now 55, once a footballer in France, Japan, Germany and, most pertinently, Celtic.

The voice has the resonance of someone who has not only survived but triumphed. Vata was once accused of treason, was a fugitive and became a nomad on the world football stage.

He chooses gratitude over resentment over past insults. “The worst emotion you can experience is fear,” he says. “That fear can create panic, it can create illness, it can create disbelief.”

But Vata, a child in Albania’s repressive communist regime, chose hope. He still does. ‘I live in hope and that’s what kept me going then.

Without hope, you have no purpose in living. When fear overcomes hope, you are lost.’ Vata found a new life after trials in his homeland.

His father, Pjeter, was wrongly suspected of treason. Vata was also investigated. Both were acquitted. Vata, the son, walked away to freedom on 30 March 1991, after playing against France at the Parc des Princes against Eric Cantona, Laurent Blanc and Basile Boli, among others.

He walked from the dressing room to the subway. He found a police station and asked for political asylum. He was 21 years old.

His career took him to France, Cyprus, Germany and Japan, but crucially to Scotland where he signed for Celtic in 1992, found his wife and made a home.

What would he be now if he had never left his homeland?

“I would have been ignorant and poorly educated,” he says.

Instead, he speaks several languages, has many business interests including a football agency, and has watched one of his sons, Ruan, grow into an astute businessman and another son, Rocco, leave Celtic to pursue his career with Watford in England.

“I’ve lived two lives,” he says. The first was under a totalitarian regime. The second has caused unrest.

But the Vata mantra is that change is not only good, but necessary. He writes in his autobiography: ‘It was not your fault if you were born in a country under a dictatorship, but if you chose to accept it.

It wasn’t your fault if you were born into poverty, but it was your fault if you chose to do nothing about it.’

So that night in 1991, he packed his bag and walked through the streets of Paris, heading into the unknown.

It is 3am and a lone jogger is running along a two-lane road, passing lorries that throw mud in his face. It is April 1991 and the scene is a road outside a refugee centre near Nantes. Vata is running towards his future.

The defender is shadowed by PSG star Patrice Loko during a UEFA Cup match

Vata played over 50 games during his time at the Parkhead club

“I trained like a beast,” he says. “Every morning I would wake up really early and go for a 10k, 15k run. I was determined to be really fit, because how else was I going to do my challenges?

I didn’t know how long it would take to arrange a trial training for me at a club.

“It’s much easier to stay in bed and wait for that call. The body says, ‘Don’t worry, just leave it.’ But my head knew it was wrong to stay in bed.

I had hunger and determination. It’s easier to give up, to lose touch with fitness, with your passion, you lose your future. I fought not to lose all those things.

I had no one to motivate me. But I had to hope because I had a goal to play in a professional football league in Europe and I was willing to do anything to achieve that.’

After brief spells in France and a return to Dinamo Tirana when the dictatorship fell, he moved to Celtic.

He joined the club when it was in a state of underperformance, winning a Scottish Cup in 1995. His time there gave him a love for Celtic and the culture he found there.

‘The most important thing I learned in Scotland is that the people are so friendly, especially the people from Glasgow. I didn’t expect that.

So kind, so helpful. I was a young man coming to a country I had no information about and they were immediately willing to help.

That was so important in my phase of life.’

He also met his wife Annefrances. Together they embarked on a football journey that included a spell in Germany, promotion to the Bundesliga with Energie Cottbus and playing in Japan.

“Life is about educating yourself and improving yourself,” he says. “When I went to Japan, I learned that children spend the first four or five years of their lives learning about morality.

I was very happy to see that.

This is a country that teaches their children to be good people from early childhood. Japan faces great difficulties — tsunami, tornado, earthquake — and they never give up, never complain. They rebuild their lives.’

It is not difficult to see a similarity with the Vata philosophy.

“I like challenges,” he says. “It’s much easier if you settle in one country and build a good life and you’re in that comfort zone.

For me it means knowing more, experiencing more.’

His son Rocco now plays for Watford, having recently joined from Celtic

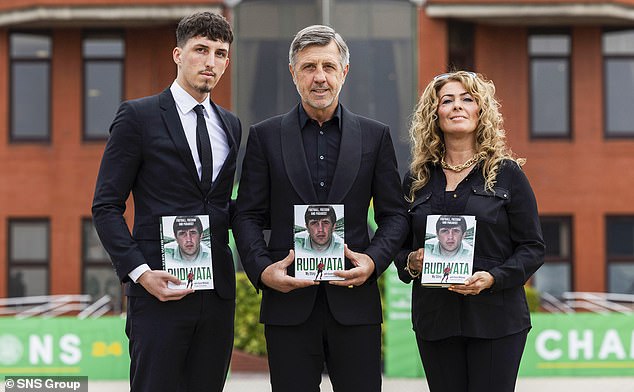

Vata is joined at the launch of his new book by his son Ruan and his wife Anne France

This was passed on to his sons.

THE view from his villa in Montenegro takes in lush trees and the sea. It also includes scenes from the past.

Vata’s mother is from Montenegro and he bought a piece of land when he was playing and built a house on it. Rocco and Ruan spent their summers there. “They played barefoot, climbed trees,” their father says. Rocco was a precocious football talent.

“He was very active, very unique,” says Vata of his 19-year-old son, who left Celtic this summer to sign for Watford. Other holidaymakers watched the young Vata shine in kickabouts. His progression has been seamless.

At the age of seven he was already in the Celtic squad and represented the Republic of Ireland (he qualified through his mother’s side) at youth level.

Yet this summer he continued.

“Leaving Celtic was painful for him,” his father says. But Vata cites the benefits of leaving a comfort zone. “It’s the best thing for any child if they want to become independent, become a strong man, become free.

“It’s good not to have to rely on your mother to do the washing and put food on the table,” he says.

But he adds: ‘It was sad when we left Celtic.

I felt empty. Rocco felt sad and in the first two or three weeks in Watford he wasn’t himself.

He’s settling in now, he’s becoming an adult. That comfort zone can destroy you. It’s a killer. Some boys don’t want to leave their environment.

They’re not willing to leave, to fight and endure pain and sacrifice. They don’t want to leave friends, girlfriends, takeaways… It’s much easier to stay.’

He knows his experience with both Rocco and Ruan has taught him lessons. “Being a father is a very difficult job,” he says. “I don’t spoil my children.

I like to show them the hard way. I want them to become strong men. Strong men create good times. Good times create weak men.’

About Rocco he says: ‘Football is a game of challenges. You have to win battles. Rocco has to develop the lion mentality if he wants to play in the Premier League eventually.

There will be elephants there. Big guys, physical.

The elephant is 10 times bigger, but the lion can eat the elephant. He will face great challenges, but I hope he has the mentality to become a lion.

“He has so much potential, I want him to make sure he doesn’t waste it. God gave him something special and he shouldn’t settle for average.”

God plays a big role in Vata’s life.

His faith is not ceremonial or tied to traditional church attendance. It is visceral. “I never complain about what God decides,” he says. “Good or bad, it’s God’s decision.

It’s what God asks us to go through. Complaining is for losers.’

He has been through a lot in the past year: his father died of an illness after a brave battle and his mother now needs support.

Rocco’s transition was also emotionally difficult.

“God plans things for you,” he says. “Things you don’t expect. You have to go through certain things.”

Vata chose freedom. He has always been willing to pay the price for it.

* Rudi Vata: My Story is published by Pitch (£25)