Smallpox warning: Vaccines may not protect against deadly new virus strain that is spreading rapidly, experts say

Scientists are warning that vaccines seen as the main hope for stopping a global outbreak of a new, deadlier MPOX variant may not even work.

Professor Marion Koopmans, director of the Pandemic and Disaster Centre at the Erasmus Medical Centre in the Netherlands, said experts simply do not know how the new clade 1b mpox virus will respond to current jabs.

“The honest answer is we don’t know yet,” she said.

The current MPOX vaccines were used against the milder variant of the virus, known as clade 2, during the global outbreak in 2022.

However, they have yet to be tested on the more powerful version that is sweeping across Africa and has now also been spotted in Europe and Asia.

And experts aren’t even sure how much protection they provided against the 2022 outbreak.

The shot is actually the vaccine given to prevent smallpox, a close relative of smallpox.

Because of the similarity between the two viruses, experts believed it would be effective, which is known as cross-protection.

But because it was deployed during a real outbreak, it was difficult to determine exactly what its benefit was, says Professor Koopermans.

Gay and bisexual men – the group most affected by mpox – are believed to have taken other measures to reduce their risk during the 2022 outbreak, such as limiting the number of new sexual partners.

“There is some evidence for clinical effectiveness of vaccinations given during an evolving outbreak while people are also doing other things to reduce transmission,” Professor Koopmans told journalists.

‘It is not so easy to say whether this offers complete protection.

‘The hope is that there will also be sufficient cross-protection for clade 1b, but that is an area where urgent research is needed.’

Professor Dimie Ogoina, an infectious diseases expert at the University of the Niger Delta, who also spoke at the event, added that another factor that could pose a challenge to a possible rollout of the mpox vaccine in Africa is who gets it first.

“Any vaccination strategy should be based on your knowledge of the epidemiology of the disease in your region,” he said.

‘I’m not sure we fully understand the transmission dynamics and risk factors for mpox in many parts of Africa.’

Like Professor Koopmans, he emphasized the uncertainties about the effectiveness of the current MPOX vaccines.

“The vaccine effectiveness studies were conducted in the Global North for clade 2b and among gay and bisexual men,” he said.

‘You cannot (guarantee) that the effectiveness rests entirely on the vaccine alone.

‘Some studies have shown that behavioural change was responsible for the decline in mpox cases in parts of Europe and America, while vaccines also helped.’

Professor Ogoina added that there were also uncertainties, such as how long the vaccines provided protection and how effective they were in children who appear to be particularly at risk in the new outbreak.

“We have not been able to replicate these studies in children and that is a major challenge, especially in the DRC (Democratic Republic of Congo), where the majority of people severely affected by this are children,” he said.

“We need to take a risk-benefit approach, particularly in the event of an outbreak, when deciding whether to vaccinate children.”

The smallpox vaccine is known to help prevent mpox because the two viruses are closely related. But experts said there was not yet enough evidence to suggest a vaccine would be effective against the new clade 1b strain

However, Professor Placide Mbala Kingebeni, an expert in epidemiology at the Clinical Research Centre of the National Institute of Biomedical Research in the DRC, the country worst hit by the ongoing outbreak, said jabs were “the best tool we have”.

“Even though we don’t have all the efficacy data, this is something we need to do,” he said.

The new variant of mpox, previously called monkeypox, is much deadlier than the mild strain that spread to more than a dozen countries, including the United Kingdom, in 2022.

The virus is designed for clade 1b mpox and kills about one in twenty adults it infects. In children, however, the death rate is one in ten.

The virus is mainly spread through skin-to-skin contact, for example through sex, or through direct care, for example from mother to child.

Clade 1b is sweeping through Central Africa, claiming hundreds of lives since the outbreak began.

In recent weeks, cases of the new variant have been discovered in Sweden and Thailand, meaning the virus has now reached both Europe and Asia.

Although no cases have been confirmed in the UK, experts suspect the new variant is already in Britain, as it can take more than two weeks for symptoms such as the classic skin lesions to develop.

However, experts say that death rates for clade 1b in Central Africa are likely unmatched in developed countries, due to greater access to higher-quality health care.

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) has already warned that it is “already planning” for cases of the new variant in the UK.

This comes as the World Health Organization has said more than £66 million ($87 million) is needed over six months to stop the current mpox outbreak.

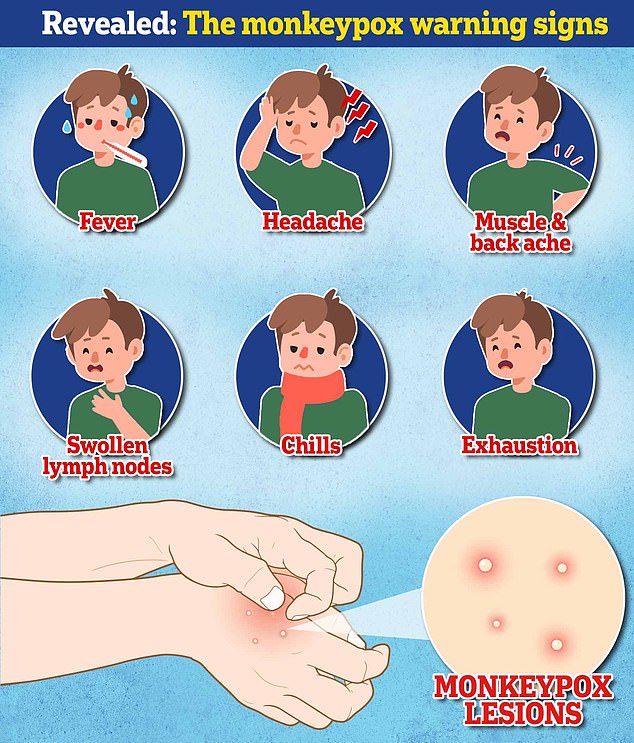

Mpox is usually ccauses characteristic lumpy lesions, as well as fever, aches and fatigue.

In a small number of cases it can spread to the blood and lungs, but also to other parts of the body, such as the brain, where it can become life-threatening.