Scientists discover a lost continent hidden between Canada and Greenland that formed 60 million years ago

Scientists have discovered a lost continent deep in the southern arm of the Arctic Ocean, which formed 60 million years ago.

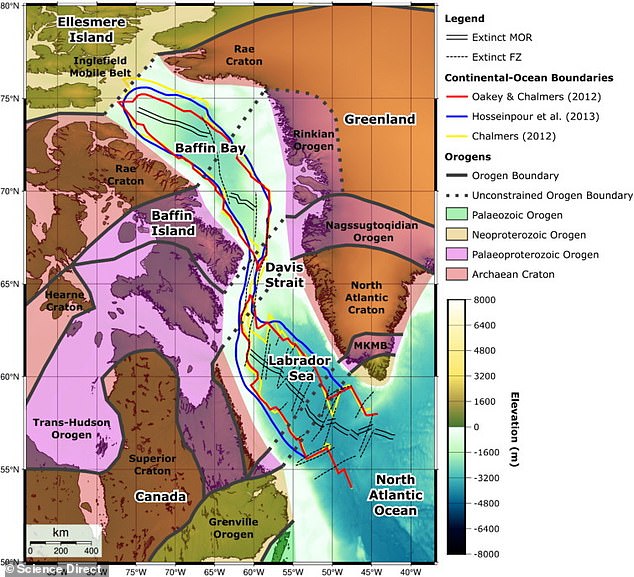

Researchers from the University of Derby in the United Kingdom accidentally discovered the 400-kilometre-long landmass beneath the Davis Strait, between Canada and Greenland, while studying plate tectonic movements in the area.

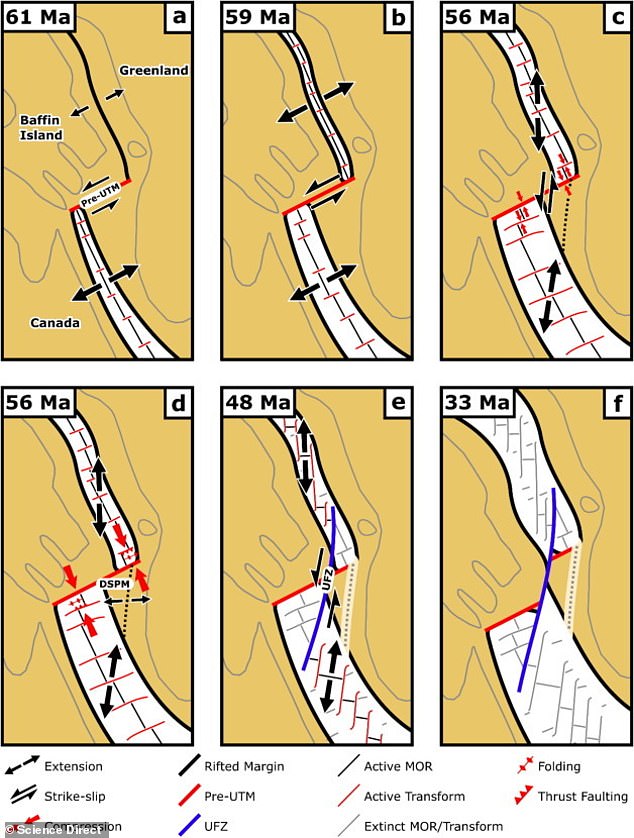

The newly discovered proto-microcontinent in the Davis Strait, a tectonic block that broke away from a continent, was formed by “a prolonged period of seafloor faulting and spreading between Greenland and North America,” researchers explain.

The team suspected that the proto-microcontinent broke away from Greenland after tectonics between the country and Canada tore it in two about 118 million years ago.

Scientists discovered a submerged microcontinent between Canada and Greenland that formed 60 million years ago. Pictured: Davis Strait where the microcontinent was discovered

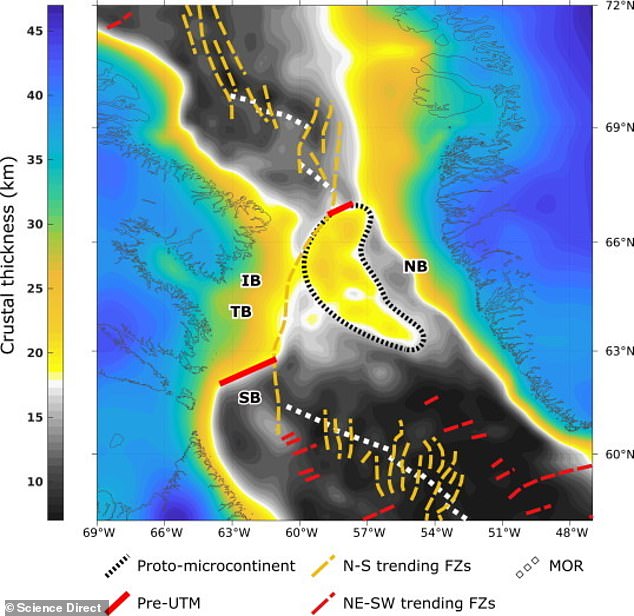

Researchers from the University of Derby were reconstructing plate tectonics in the area when they discovered a thick crust extending for almost 250 miles beneath the Davis Strait. Pictured: The Davis Strait Proto-microcontinent lies beneath the water in the Davis Strait

“Rifting and microcontinent formation are absolutely ongoing phenomena – with every earthquake we are potentially working towards the next microcontinent separation,” said Dr Jordan Phethean Physical.org.

“The goal of our work is to understand their origins so well that we can predict their future evolution.”

Researchers identified the new microcontinent using a combination of crustal thickness data from gravity maps, seismic reflection data and plate tectonics modeling.

Gravity maps contain information about the density of rocks and the depth and distribution of the source rocks of the anomalies.

The team focused on how the crustal anomaly formed by reconstructing tectonic movements that lasted about 30 million years.

They described the protomicrocontinent as larger than other microcontinents, with a thickness of 18 to 22 kilometers. According to them, it is of great importance for today’s science to understand how it formed.

The average microcontinent is between five and twenty kilometers thick.

The mapping techniques tracked how seafloor movements had changed over millions of years and identified “an isolated area of relatively thick continental crust that had separated from Greenland during a newly recognized phase of (east-west) extension along West Greenland,” the study.

According to researchers, the Davis Strait is one of the largest concentrations of known fault structures with well-defined changes in plate movement. These changes can help us understand how microcontinents form.

Protomicrocontinents are part of the continental lithosphere. This is a part of the Earth’s outer crust that is divided into several tectonic plates (rock plates).

About 50 to 120 miles (80 to 190 kilometers) below the Earth’s surface is a semi-liquid layer of rock that heats and then melts, causing the rock to flow.

The movement pushes the tectonic plates together, causing them to grind against each other for millions of years, which can lead to earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

When this happens, the landmass will break away from the major continents and create its own proto-microcontinent.

Protomicrocontinents are part of the continental lithosphere, a portion of Earth’s outer crust that is divided into several tectonic plates – slabs of rock. Pictured: Tectonic plates shifting over millions of years

The research team used maps created from gravity and seismic reflection data, which depict images of the Earth’s subsurface using sound waves, to determine the age and location of the fault lines. Pictured: An overview of the tectonic plates in the Davis Strait

The first rift between Canada and Greenland began about 118 million years ago, but the seafloor did not begin to spread until 61 million years ago, creating what we now know as Davis Strait.

After about three million years, scientists reported that the seafloor spreading shifted from northeast-southwest to north-south, causing the proto-microcontinent Davis Straight to break off.

The shift lasted about 33 million years and only stopped when Greenland collided with Ellesmere Island, which lies to its north.

The researchers hope their findings can be used to understand how other proto-microcontinents form around the world, including the microcontinent Jan Mayen northeast of Iceland and the Gulden Draak Knoll off the coast of Western Australia.

“Rifting and microcontinent formation are absolutely ongoing phenomena. With each earthquake, we are potentially working toward the next microcontinent separation,” Phethean said. Physical.org.

“The goal of our work is to understand their origins so well that we can predict their future evolution.”