Is there life on Venus? Scientists detect traces of phosphine and ammonia in the planet’s clouds – and say they could be coming from microbes

With its high temperatures and acidic clouds, it is one of the most impressive planets in our solar system.

But exciting new findings suggest that life may exist on Venus, the second planet from the sun.

Researchers have found traces of ammonia and phosphine in the planet’s clouds – two potential ‘biomarkers’ of life.

On Earth, both compounds are formed during the decomposition of organic material, such as plants and animals.

Since there are currently no other known natural processes for its production on Venus, it could be produced by something scientists are unaware of.

Today, Venus is the hottest planet in the solar system, with a surface hot enough to melt lead and a thick atmosphere filled with toxic clouds of sulfuric acid

It follows the original discovery of phosphine in the clouds of Venus in 2020, although the findings were quickly dismissed by skeptics.

The new findings were presented on Wednesday at the National Astronomy Meeting 2024 at the University of Hull.

Professor Jane Greaves, an astronomer at Cardiff University and author of the findings, said ammonia had been detected in the solar system before, but near the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn.

‘That’s quite natural because the gas is mostly hydrogen,’ she told MailOnline.

‘On rocky planets like Earth or Venus this is much rarer.’

Ammonia is a colourless, poisonous gas that occurs in nature and is mainly produced during the anaerobic decomposition of plant and animal material.

Professor Greaves and colleagues discovered the gas in Venus’ clouds using the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia.

The gigantic 2.3-hectare dish detects weak radio waves that reach us from objects in space.

“Simply put, the Green Bank telescope captures a rainbow of light, but in radio light,” said Professor Greaves.

“If there is light missing, it is because a molecule has absorbed it. We use the exact wavelength to identify the molecule.”

The ammonia was found in the upper parts of the planet’s clouds, where it is too cold for life.

However, it is also possible that the ammonia is located in the deeper, warmer part of the clouds and then rises to the higher parts.

That is what the researchers will now try to determine.

Professor Greaves and colleagues discovered ammonia there using the Green Bank telescope in West Virginia (pictured)

Thanks to its dense atmosphere, Venus is even hotter than the planet Mercury, even though the latter orbits closer to the Sun

Meanwhile, phosphine was discovered by a team led by Professor Greaves and Dr Dave Clements from the Department of Physics at Imperial College London, by studying data from the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii.

Phosphine is a colorless gas that smells like garlic or rotting fish. It is produced naturally on Earth by certain microorganisms in the absence of oxygen.

It can also be released in small quantities during the decomposition of organic material, or synthesized industrially in chemical plants.

Dr. Clements stressed that the detection of both gases on Venus is not evidence of life and that it is unknown what processes emit these gases.

‘It’s most likely a chemical process that we don’t understand at the moment and don’t know about yet,’ he told MailOnline.

But phosphine has been proposed as a biomarker for exoplanets [planets outside our solar system]and on Earth it is only found in association with life, so life is also a possibility.

“We don’t know yet. More observations and more laboratory and theoretical work are needed to understand what’s going on. Maybe future missions to Venus can help as well.”

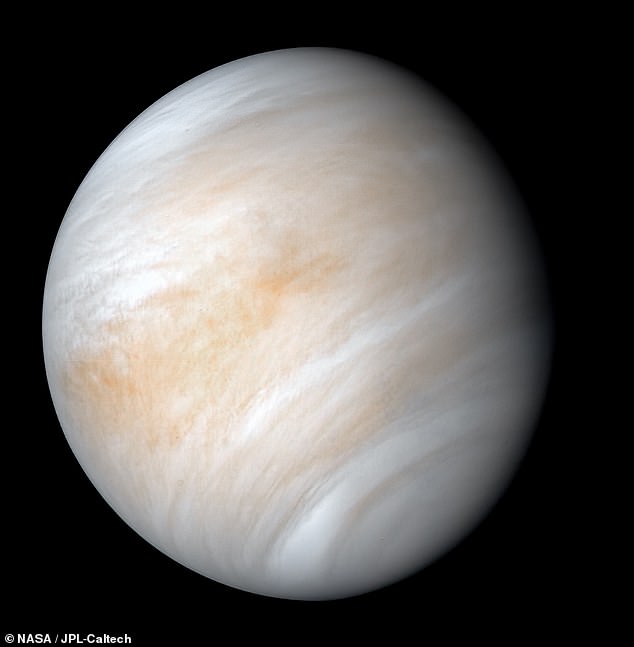

Traces of phosphine gas found in the clouds above Venus (seen here in an image taken by NASA’s Mariner 10 spacecraft) could indicate that the planet supports microbial life

Venus is known as Earth’s “evil twin” because it’s also rocky and about the same size. However, its average surface temperature is a sweltering 465°C (870°F).

Thanks to its dense atmosphere, Venus is even hotter than the planet Mercury, even though the latter orbits closer to the Sun.

The rocky orb is not only inhospitable, but also sterile – with a surface hot enough to melt lead and toxic clouds of sulfuric acid.

Because the clouds are so acidic, the phosphine would break down very quickly and therefore must be constantly replenished.

However, there is a general belief within the astronomical community that the planet was not always such an unfriendly place.

Perhaps as recently as 700 million years ago, Venus had oceans similar to those on Earth, so life as we know it could have existed there.

But these oceans evaporated when our neighboring planet experienced a ‘runaway greenhouse effect’: a dramatic increase in temperature.

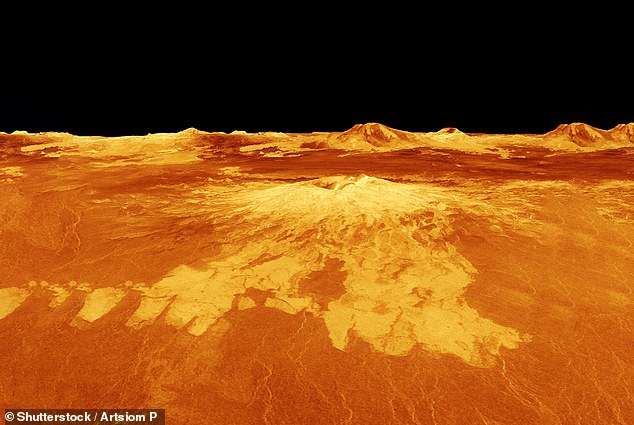

Venus is known as Earth’s “evil twin” because it is also rocky and about the same size, but its average surface temperature is a scorching 870°F (465°C). The image shows the surface of Venus as interpreted by the Magellan spacecraft.

In 2020, scientists discovered traces of phosphine gas in the planet’s clouds, which they said could have come from microbes.

Professor Greaves and his colleagues observed Venus at the time using both the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile.

They discovered a so-called ‘spectral signature’ unique to phosphine and estimate that the gas is present in Venus’ clouds at an abundance of about 20 parts per billion.

However, other scientists claimed they could not find the same signal, and members of Greaves’ team admitted a calibration error had been made and downgraded the strength of their claims.

Now, using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, Dr. Clements has again been able to find phosphine and he suspects that it is destroyed by sunlight during the day.

Photograph of the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii (center). On the left is the Caltech Submillimeter Observatory, and on the right is the Smithsonian Submillimeter Array.

“The UV radiation in sunlight breaks down the molecule, which could explain why some observations have found phosphine and others have not,” Dr. Clements said.

Dr Robert Massey, deputy executive director of the Royal Astronomical Society who was not involved in the research, called the findings “very exciting”.

‘But it must be stressed that the results are only preliminary and more research is needed to learn more about the presence of these two potential biomarkers in the clouds of Venus,’ he told MailOnline.

‘Still, it’s fascinating to think that these detections could indicate possible signs of life or unknown chemical processes.

“It will be interesting to see what further research reveals in the coming months and years.”