We have a touchdown! China makes history by returning first rocky samples from the far side of the moon – which experts say could reveal more about the solar system’s early history

China has made space history again as its lunar lander returns to Earth with the first rock samples from the far side of the moon.

The Chinese lunar probe Chang’e-6 landed in China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region this morning at 06:07 GMT (2:07 PM Beijing time).

Chang’e-6 returned its precious cargo to Earth after a months-long journey to the largely unexplored far side of the moon.

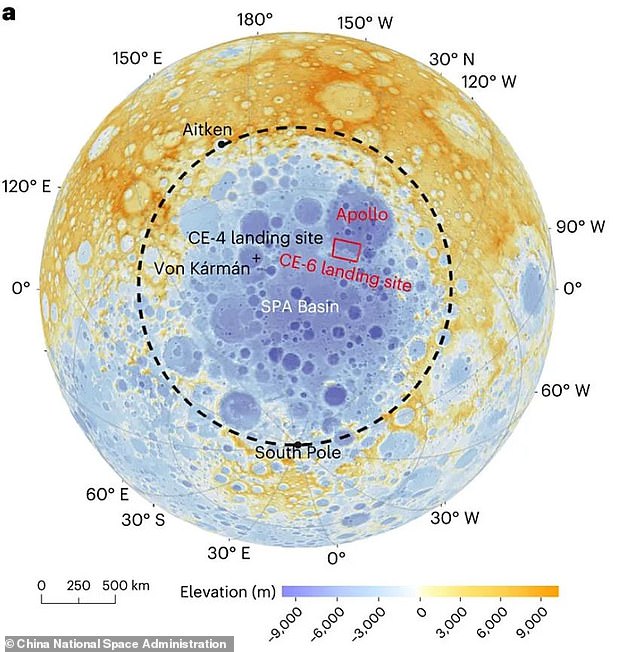

It brought back up to 2 kg of rocky lunar regolith collected by a drill from the moon’s South Pole-Aitken Basin.

Scientists eagerly await the opportunity to study these samples, which could provide crucial clues about the early history of the solar system.

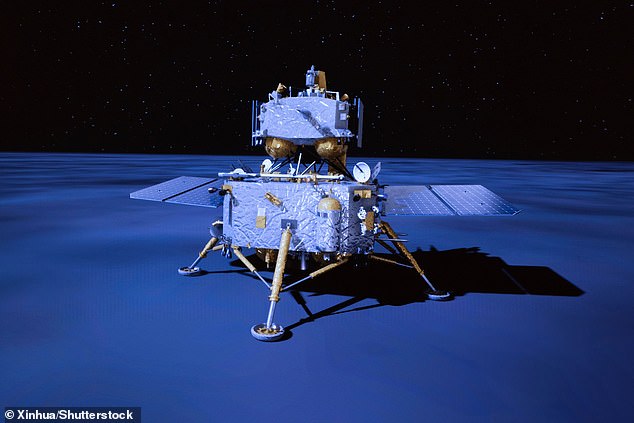

The Chinese lander Chang’e-6 (pictured) has returned to Earth with the first rocky samples from the far side of the moon

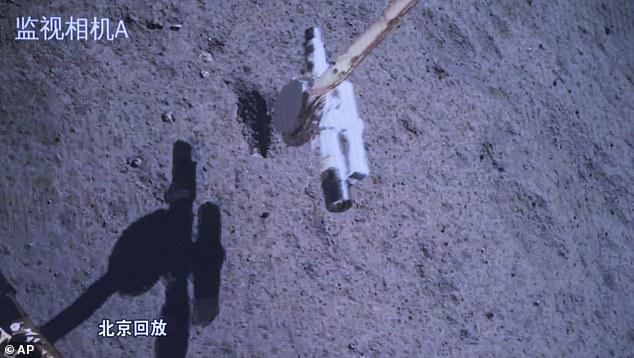

The lander has collected approximately 2 kg of rocks and regoliths from the lunar surface and has now returned them safely to Earth

After the aircraft landed via parachute in Inner Mongolia, a team of scientists reached the module within minutes.

“I hereby declare that the Chang’e 6 lunar exploration mission has been a complete success,” Zhang Kejian, director of the China National Space Administration, said at a televised news conference shortly after landing.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping sent a congratulatory message to the Chang’e team, saying it was a “landmark achievement in our country’s efforts to become a space and technological power.”

According to CCTV, a state broadcaster, the samples will now be airlifted to Beijing for the sample container and its contents to be removed.

Chang’e-6 collected the rocks from the moon’s South Pole-Aitken Basin, a crater believed to have formed more than 4 billion years ago

After collecting the samples, the ascent module (photo) detached from the lander and returned to the moon’s orbit

These samples are of particular scientific interest because they are the first ever collected from the Antarctic-Aitken Basin.

This 1,500-mile-wide (2,500 km) is believed to have formed 4.26 billion years ago.

That makes it hundreds of millions of years earlier than many of the other craters on the moon’s surface that formed during an event called the “late heavy bombardment.”

The samples could reveal more about the very early formation of the moon and possibly also show whether there is enough water at the moon’s south pole to support human colonies.

They “are expected to answer one of the most fundamental scientific questions in lunar science: What geological activity is responsible for the differences between the two sides?” said Zongyu Yue, a geologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Chinese scientists are expected to conduct initial analysis of the samples before sharing data and collaborating with international researchers.

Chang’e-6 consists of four main components: the lander, the return capsule, an orbiter and a small rocket carried to the moon, called an ascendant.

The probe took off from Earth on March 3 aboard a Chinese Long March rocket that carried it into orbit around the moon.

On June 1, the orbiter and lander modules separated and the spacecraft made its perilous descent to the lunar surface.

The samples (pictured during the collection) could provide scientists with insight into the early formation of the solar system

After successfully making a soft landing near the moon’s south pole, the craft used a drill and shovel to collect regolith and rock samples.

These samples were then returned to orbit aboard the riser, which rendezvoused with the orbiter on June 6 and began the journey back to Earth on June 21.

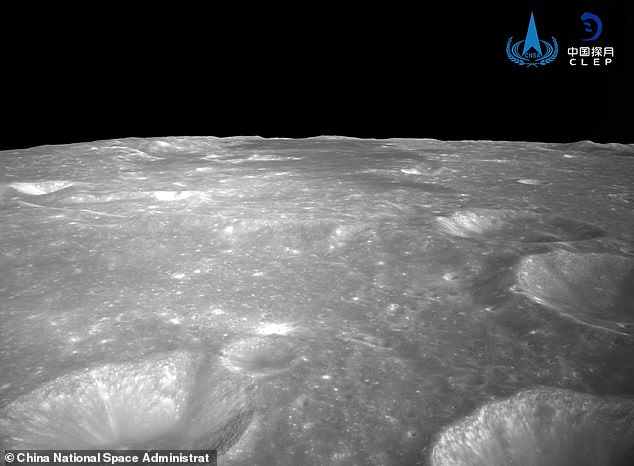

This mission was particularly technically challenging because no radio signal from Earth can directly reach the far side of the moon – a largely unexplored region of the moon.

Because the moon is ‘tidally fixed’ to the Earth, it rotates in exactly the same time as it takes to orbit the Earth.

This causes one side of the moon to permanently face away from the planet, although it is not permanently dark, as the misnomer “dark side of the moon” suggests.

Because the far side of the moon (imaged by Chang’e-6) has no plate tectonics, the ancient craters provide a window into how the planet formed

To reach the other side, signals must be sent via a relay satellite that must be placed in lunar orbit before landing.

Chang’e-6 received its control signals via Queqiao-2, a 1,200 kg relay satellite that was launched into orbit in March to bounce signals back to Earth.

This is the sixth of eight missions in China’s ambitious moon program and the second time the country has placed a lander on the far side of the moon – but this early mission did not return to Earth.

Looking ahead, the country plans to launch Chang’e-7 in 2026 and Chang’e-8 in 2028.

Chang’e-8 will test technologies needed to establish a manned base at the moon’s south pole by 2030.

Because this part of the moon is believed to be rich in frozen water, there is an escalating space race between countries seeking to establish a permanent presence.

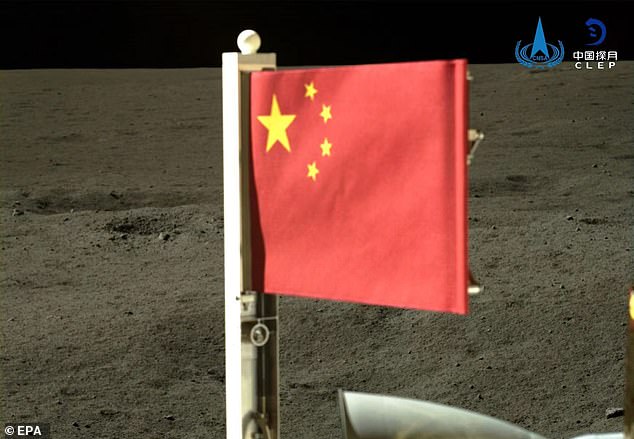

During the mission, Chang’e-6 also flew a Chinese flag made from volcanic basalt rock fibers that could remain on the moon for 10,000 years

Chang’e-6 also highlighted some technologies that could pave the way for its base-building ambition.

Before returning to Earth, the lander waved a Chinese flag made of volcanic basalt rock fibers that could potentially remain on the moon for 10,000 years, according to the Chinese National Space Agency.

These fibers are created by heating and stretching rocks, similar to those on the moon, and are resistant to corrosion and heat.

Professor Zhou Changyi, one of the rover’s designers, told state broadcasters: “In the future, such basalt fibers can also be used on the moon to make other things.”

Unlike the flags placed during the Apollo missions, Chang’e was 6’s A small flag appeared on a retractable arm that deployed from the side of the lunar lander and was not placed on the lunar ground, according to an animation of the mission released by the agency.