Ancient Egyptians Tried to Treat CANCER: ‘Extraordinary’ 4,000-Year-Old Skull Has Cuts That Suggest Doctors Tried to Operate on a Tumor

An ‘extraordinary’ 4,000-year-old Egyptian skull shows signs of attempts to treat cancer.

Lacerations on the skull may indicate that ancient Egyptians tried to operate for excessive tissue growth, scientists say.

An alternative theory is that they were trying to learn more about cancer conditions after the death of a patient.

Evidence in ancient texts shows that the ancient Egyptians were – for their time – ‘exceptionally skilled’ in medicine.

They could identify, describe and treat diseases and traumatic injuries and even place dental fillings.

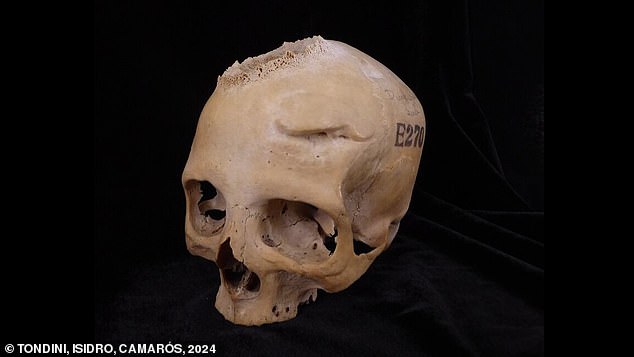

An ‘extraordinary’ 4,000-year-old Egyptian skull shows signs of attempts to treat cancer. Lacerations on the skull may indicate that ancient Egyptians tried to operate for excessive tissue growth, scientists say

Microscopic observation revealed a large lesion on the skull consistent with excessive tissue destruction, a condition known as neoplasm.

They could not treat other conditions, such as cancer.

But a new study published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine strongly suggests they may have tried.

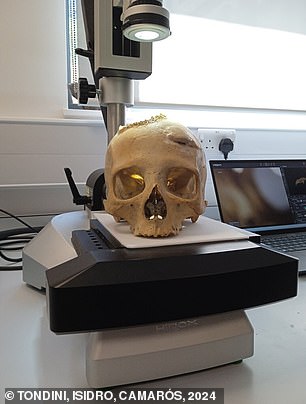

An international team of researchers examined two human skulls, each thousands of years old.

First author Tatiana Tondini, researcher at the University of Tübingen, Germany, said: ‘We see that although the ancient Egyptians were able to deal with complex skull fractures, cancer was still an area of medical knowledge.

‘We wanted to learn about the role of cancer in the past, how widespread this disease was in ancient times, and how ancient societies dealt with this pathology.

‘When we first observed the cut marks under the microscope, we couldn’t believe what was in front of us.’

In the study, an international team of researchers examined two human skulls, each thousands of years old

There were approximately 30 small and round metastatic lesions distributed throughout the skull. But what stunned the researchers was the discovery of cuts around the lesions, likely made with a sharp object such as a metal instrument.

Lead author Prof. Edgard Camarós from the University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, said: ‘This finding is unique evidence of how ancient Egyptian medicine would have attempted to tackle or investigate cancer more than 4,000 years ago.

“This is an extraordinary new perspective in our understanding of the history of medicine.”

The team examined two skulls from the Duckworth Collection at the University of Cambridge.

Skull and mandible 236, dated between 2687 and 2345 BC, belonged to a man aged 30 to 35 years, while skull E270, dated between 663 and 343 BC, belonged to a woman older than 50 years.

Microscopic observation revealed a large lesion on the skull consistent with excessive tissue destruction, a condition known as neoplasm.

There were approximately 30 small and round metastatic lesions distributed throughout the skull.

The researchers say studying skeletal remains poses certain challenges that make definitive statements difficult, especially because remains are often incomplete and there is no known clinical history.

But what stunned the researchers was the discovery of cuts around the lesions, likely made with a sharp object such as a metal instrument.

Co-author Prof. Albert Isidro, a surgical oncologist at Sagrat Cor University Hospital, Spain, said: ‘It appears that the ancient Egyptians performed some kind of surgical procedure related to the presence of cancer cells, proving that the ancient Egyptian medicine also performed experimental treatments. or medical explorations in relation to cancer.’

The researchers said skull E270 also shows a ‘large lesion’ consistent with a cancerous tumor that led to bone destruction

The researchers said that skull E270 also shows a “large lesion” consistent with a cancerous tumor that led to bone destruction.

They said their findings may indicate that while current lifestyles, aging people and environmental carcinogens increase the risk, cancer was also a common disease in the past.

The team also found two healed lesions from traumatic injuries on the E270 skull.

They said one of them appears to be from a “close-range violent event” involving the use of an edged weapon.

The research team believes that the healed lesions may mean that the woman may have received some form of treatment and as a result survived.

It is unusual to see such a wound on a woman, and most violence-related injuries are found in men.

Tondini said: ‘Was this female person involved in any form of warfare?

“If so, we need to reconsider the role of women in the past and how they actively participated in conflicts in ancient times.”

But the researchers say studying skeletal remains poses certain challenges that make definitive statements difficult, especially because remains are often incomplete and no clinical history is known.

Prof Isidro said: ‘In archaeology we work with a fragmented part of the past, which makes an accurate approach difficult.’

Prof Camarós added: ‘This study contributes to a change of perspective and provides an encouraging basis for future research in the field of paleo-oncology.

‘But more studies will be needed to disentangle how ancient societies dealt with cancer.’