‘Doomsday Glacier’ in Antarctica is melting ‘much faster’ than previously thought, scientists warn

Antarctica’s ‘Doomsday Glacier’, nicknamed for its ability to raise sea levels by almost two feet, is breaking up ‘much faster’ than previously thought.

Formally known as the Thwaites Glacier, researchers from the University of California (UC) discovered that warm seawater flows miles underground, causing ‘powerful melting’.

The team used satellites and radar technology to monitor changes in surface elevation and found that the water had lifted parts of the glacier about seven miles.

The findings could require a reassessment of global sea level rise projections, as researchers predicted Thwaites could retreat up to three kilometers each year under the influence of warm seawater.

Antarctica’s ‘Doomsday Glacier’, nicknamed for its ability to raise sea levels by nearly two feet, is falling apart ‘much faster’ than previously thought

Co-author Christine Dow, professor in the Faculty of Environment at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada, said in a statement: ‘Thwaites is the most unstable site in Antarctica and contains the equivalent of 60 centimeters [1.9 feet] of sea level rise.

‘The concern is that we are underestimating the rate at which the glacier is changing, which would be devastating to coastal communities around the world.’

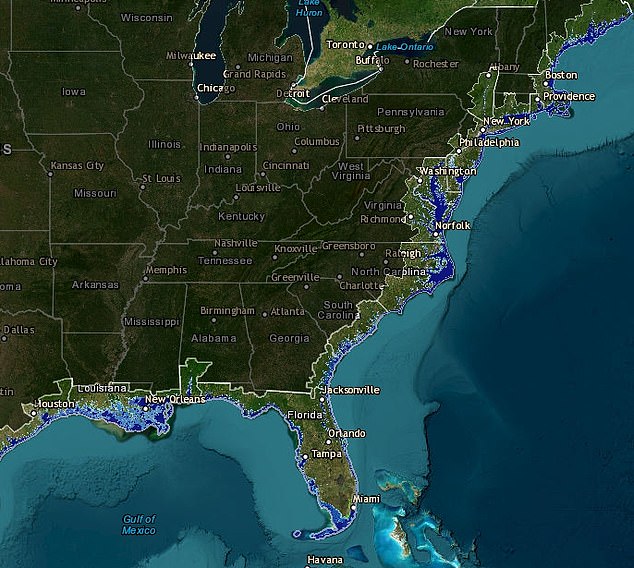

Data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows that a sea level rise of more than 2 feet would inundate many of America’s coastal cities, including Miami, New York City and New Orleans.

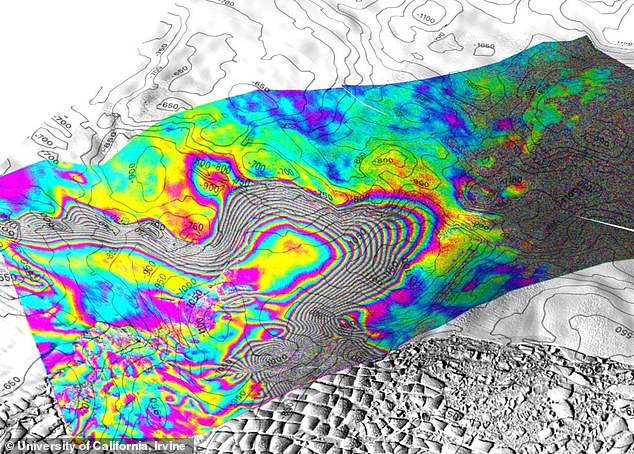

The team used data collected from March to June 2023 by the Finnish commercial satellite mission ICEYE, which showed the rise, fall and flexure of the Thwaites Glacier.

Lead author Eric Rignot, professor of Earth system sciences, said: ‘These ICEYE data provided a long series of daily observations that closely match tidal cycles.

‘In the past, we had sporadically available data, and with only those few observations it was difficult to figure out what was going on.

‘If we have a continuous time series and compare it with the tidal cycle, we see that the seawater comes in at high tide and withdraws and sometimes penetrates further under the glacier and becomes trapped.’

Data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows that a sea level rise of more than two feet would inundate many of America’s coastal cities, including Miami, New York City and New Orleans.

The team used satellites and radar technology to monitor changes in surface elevation and found that the water had lifted parts of the glacier about seven miles. The satellite images (photo) captured the warm seawater flowing under the glacier as an incoming and outgoing tide

The team determined that the seawater entered from the bottom of the ice sheet and combined with fresh water generated by geothermal flux and friction, accumulated and “had to flow somewhere.”

The water is then distributed through natural conduits or collects in cavities, creating enough pressure to raise the ice sheet.

“There are places where the water is almost at the pressure of the overlying ice, so it takes just a little bit more pressure to push the ice up,” Professor Rignot said.

“The water is then compressed enough to lift a column of more than half a mile of ice.”

Researchers have been monitoring the impact of climate change on ocean currents for decades, finding evidence that warmer seawater is being pushed toward the coasts of Antarctica and other polar regions.

West Antarctica, home to the ‘Doomsday Glacier’, has specifically experienced warming over the past fifty years.

Previous studies have shown that higher temperatures warm the oceans, making them less cold and less likely to sink.

Without sinking cold water, ocean currents can slow or stop in one spot, which could explain why warmer seawater isn’t moving quickly through Antarctica.