Deep sea expedition uncovers more than 50 never-before-seen species off the coast of Chile – from a ‘flying spaghetti monster’ to a glow-in-the-dark dragonfish

Glow-in-the-dark dragonfish and flying spaghetti monsters might seem better suited to fantasy than science.

But these are just a few of 50 never-before-seen species discovered during an expedition off the coast of Chile.

An international team of scientists has mapped 78,000 square kilometers of seabed along the Salas y Gómez ridge near Rapa Nui, also called Easter Island.

Along this 2,900 km long ocean mountain range, the researchers observed 160 species, almost a third of which were new to science.

Dr. Javier Sellanes from the Universidad Católica del Norte said: ‘The amazing habitats and animal communities we revealed during these two expeditions provide a dramatic example of how little we know about this remote area.’

Researchers have found a ‘Flying Spaghetti Monster’ (pictured) among 160 other species during an expedition along the Salas y Gómez ridge near Rapa Nui

The Bathyphysa siphonophore was named after the Flying Spaghetti Monster (pictured) by the oil rig workers who first found one because of its many tentacles

Salas y Gómez Ridge extends from the island of Rapa Nui in the Pacific Ocean to just off the coast of Chile.

This ridge consists of 110 seamounts: underwater mountains that are particularly rich in marine life.

This area supports several ecosystems, such as glass sponge gardens and deep coral reefs, and also supports the migrations of animals such as whales, sea turtles and sharks.

The forty-day expedition explored ten seamounts and two islands.

The team’s goal was to collect data on the Salas y Gómez Ridge as part of an application for the designation of a protected area on the high seas under the UN High Seas Convention.

This follows the researchers’ previous expedition to the nearby Nazca and Juan Fernandez Ridge, which found more than 100 suspected new species.

The Salas y Gómez Ridge is a 2,900 kilometer long ocean mountain range that extends from Rapa Nui, also called Easter Island, towards the coast of Chile

The researchers mapped 10 of the 110 seamounts: underwater mountains that make up the ridge

Their discoveries revealed a wide range of unique species, such as this diadem sea urchin

Some parts of the ridge that lie within Chile’s territory are already protected, but many of the seamounts are in international waters and are unprotected.

Dr. Sellanes said: ‘These expeditions will help alert decision-makers to the ecological importance of the areas and help strengthen conservation strategies within and beyond jurisdictional waters.’

Species in need of protection include the Bathyphysa siphonophore – a particularly strange creature often called the ‘flying spaghetti monster’ because of its many tentacles.

Siphonophores, an animal family that includes the Portuguese Man O’ War, are gelatinous wanderers made up of thousands of specialized parts.

Although these aliens look like one animal, they are actually colonies of individual organisms that all perform different tasks.

The researchers also found a Galaxy Siphonophore, a relative of the flying spaghetti monster, which uses its web of tentacles to catch fish, plankton and small crustaceans.

Siphonophores like this Galaxy Siphonophore (pictured) are colonies of highly specialized organisms that work together to form huge animals

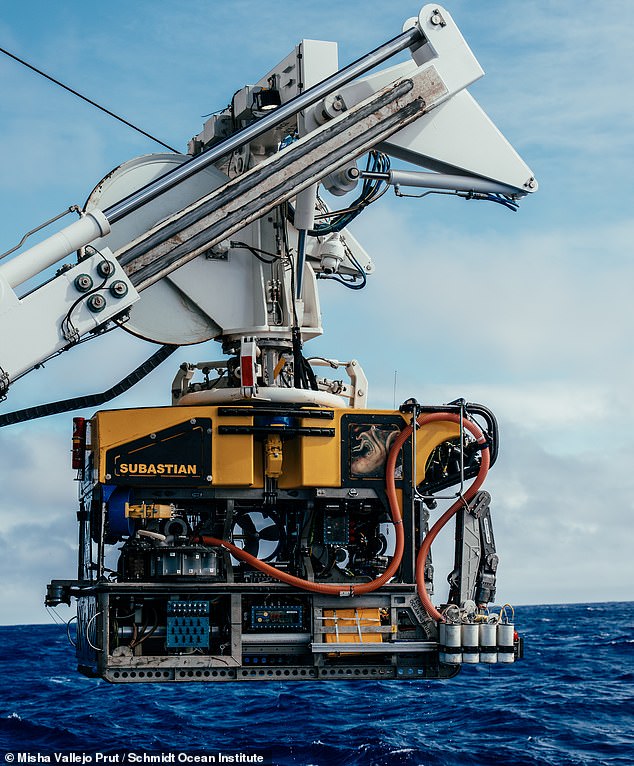

The researchers used a remotely piloted vehicle called SuBastian to study the complex ecosystems in this region of the Pacific Ocean

Another incredible animal found by the researchers was the deep-sea dragonfish.

These undersea apex predators are known for their enormous jaws and fearsome teeth that they use to capture prey.

This particular fish demonstrated this as well a beautiful example of bioluminescence.

At an altitude of about 1500 meters, where the dragonfish have their home, almost no light from the sun can penetrate.

This means that many creatures in the so-called ‘bathypelagic zone’ produce their own light through chemical processes.

Some use this light to communicate and find mates, while others, like the dragonfish, use their lights to lure unsuspecting prey.

Researchers also discovered a glow-in-the-dark deep-sea dragonfish (pictured), a fierce apex predator that lives outside the light of the sun

Many creatures like this corona star starfish make the rock walls of seamounts their home because of the upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water

The scientists found the deepest known photosynthesis-dependent animal, the Leptoseris, better known as a ripple coral (photo)

In addition to these incredible species, the researchers also found large octopuses, stocky lobsters, starfish and even the world’s deepest coral that relies on photosynthesis.

This great diversity of life is made possible by the seamounts themselves, which form islands of biodiversity in the depths of the ocean.

When these underwater mountains are hit by fast currents, they act like a rock in a stream, forcing the water to flow up and around them.

This causes cold, nutrient-rich water from the ocean floor to rise to the surface, causing an explosion of life.

The current also washes sand away from the rock face, creating a surface for stationary creatures such as anemones and coral to anchor themselves to.

The Salas y Gómez Ridge is being considered for the designation of a protected area on the high seas due to its high biodiversity

Some parts of the ridge are protected under Chile’s jurisdiction, but others, such as this coral garden, are in international waters and unprotected

The researchers hope their findings will make a case for protecting the Salas y Gómez Ridge and its wildlife, to ensure creatures like this hydroid are not lost

The researchers say these factors make each of the 110 seamounts a distinct and valuable environment.

Lead scientist Dr. Erin Easton of the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley said, “The observation of diverse ecosystems on individual seamounts highlights the importance of protecting the entire ridge, not just a few seamounts.”

Although consideration is currently being given to making the Salas y Gómez ridge a protected area, this change is not yet enforceable under international law.

Today, 83 countries, including the US, Australia and Britain, have signed the UN High Seas Treaty, but only Chile and Palau have ratified the treaty.

Only after 60 countries have joined them will countries with sufficient scientific data be able to establish marine protected areas in international waters.

The researchers hope their efforts will build a case to protect the ridge if the law is ratified.

Dr. Easton added: ‘These expeditions will help alert decision-makers to the ecological importance of the areas and help strengthen conservation strategies within and beyond jurisdictional waters.’