Fireproof chemicals in your smartphone could quadruple the risk of dying from cancer, research suggests

Chemicals used to make your smartphone fireproof could pose a greater risk of fatal cancer, a study suggests.

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) have been used since the 1970s for their ability to slow the spread of a fire, potentially saving thousands of lives.

But now, in a study that followed 1,100 American adults for 20 years, researchers have found that those with the highest levels of the chemicals in their blood were four times more likely to die from cancer than those exposed to the lowest amounts.

Thyroid cancer in particular was the most common, with a survival rate of less than four percent if detected in the late stages.

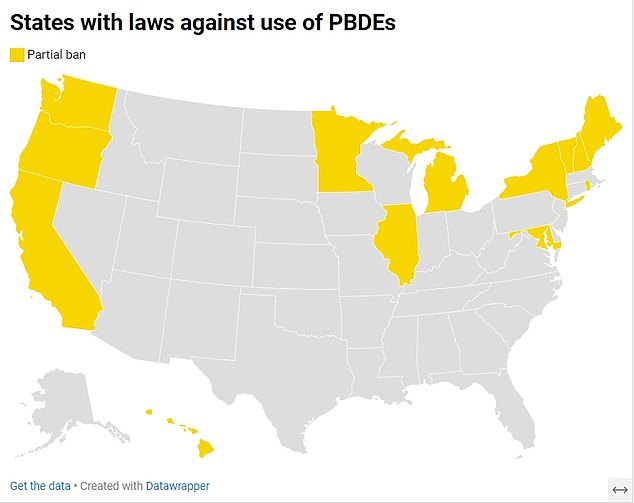

The map above shows states that have implemented bans on certain forms of PBDEs. They are banned in many countries, including the European Union

Scientists in China, who conducted the study, warned that PBDEs can become detached from objects and form dust.

These can then enter humans through inhalation or as contaminants in food, disrupting hormones and damaging genes, increasing the risk of cancer.

a study from 2017 When testing 64 mobile phones and PCs (from manufacturers such as Apple, Samsung and Dell), 60 percent showed PBDEs on their surfaces. Apple says it no longer uses the chemical in its smartphones.

The flame retardant chemical is also found in other items including sofas, chairs, car seats and children’s toys.

Many countries, including those in the European Union, have already banned or drastically restricted the use of these chemicals.

But in the US, only thirteen states – including New York, California and Maine – have introduced a ban. Even then, only certain types of the chemical are restricted.

The scientists wrote in the article: ‘As (endocrine) disrupting chemicals, PBDEs and their metabolites can bind to hormone receptors (i.e. the estrogen receptor)… and subsequently disrupt hormone homeostasis.

‘This plays a role in the development and progression of endocrine tumors such as thyroid cancer.’

The study also found that participants with the highest levels of the toxin in their blood had a 43 percent higher risk of death from all causes, and death from any cause.

But they said this was not a significant link – and that more research was needed.

The researchers said their study was the first to examine the link between PBDE exposure and the risk of death from specific causes, including cancer.

For the study, researchers recruited participants from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in the US, which surveys 5,000 adults and children annually.

Participants were recruited from the survey conducted in 2003 and 2004. They were on average 42 years old and all had blood test results for PBDEs.

They were then followed for 17 years, with data checked for death and cause of death.

During the study period, 199 participants died – or 18 percent of participants.

The team then conducted an analysis that took into account factors such as age, gender, ethnicity and obesity status.

The results revealed a 300 percent increased risk of cancer death among those with the highest levels of the toxin in their blood, compared to those with the lowest risk.

It also showed that those with the highest levels of the chemical had an eight percent lower risk of death from cardiovascular disease compared to those with the highest levels.

The study could only find links, but could not prove that the chemicals had caused the increase in cancer cases.

However, previous studies have also warned about the risks of the chemicals, including that they could cause obesity in children.

The team, which examined thousands of cases, found that the chemicals can affect thyroid hormone levels and cause inflammation in pregnant women, leading to high birth weight and premature birth.