Millions of transparent blob-like creatures are washing up on the west coast due to warming oceans…do you know what they are?

Millions of bizarre blob-like creatures have washed up on West Coast beaches in recent years due to warming waters caused by climate change.

The gelatinous, transparent mases are found along the coasts of Northern California and Oregon, and sometimes as far away as Alaska, but typically live in warm seas – and at great depths.

Now scientists from Oregon State University have discovered that these pyrosomes or ‘sea pickles’ are appearing en masse as a result of a major marine heat wave that began in 2013 – marking the first time the animals have been seen in 25 years.

Since the proliferation of pyrosomes in the Pacific Ocean, they have also consumed most of the energy in the sea, reducing the number of salmon and seabirds.

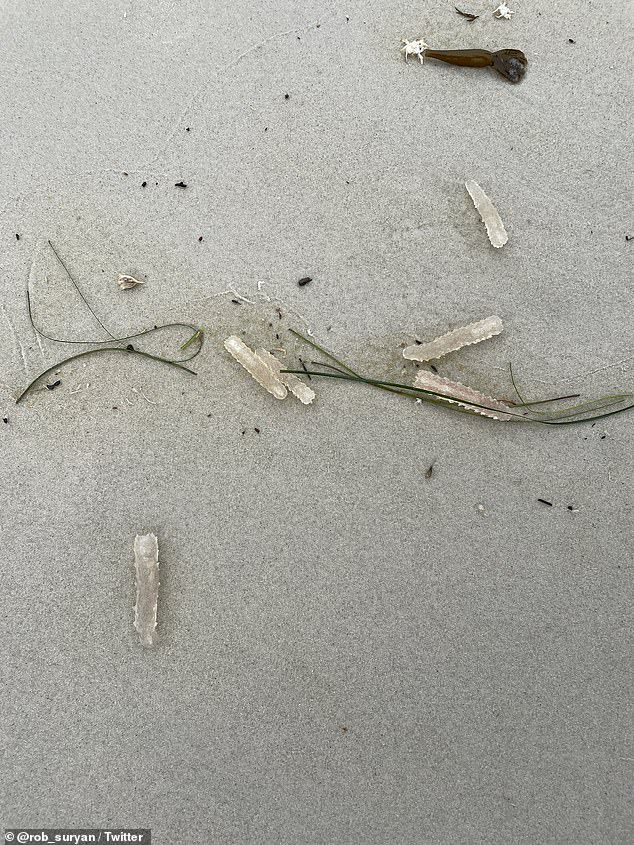

Pyrosomes are a gelatinous, blob-like creature that resembles a pink tube with stiff bumps covering the body

Pyrosomes wash up on the coasts of Oregon and Northern California

Pyrosomes feed on phytoplankton, which form the basis of marine food webs that provide food for a wide range of marine animals, but growing numbers of sea pickles mean there are not enough available.

These creatures can grow from just a few centimeters to up to 20 meters in length and resemble a pink tube with stiff bumps covering the body.

Pyrosomes are colonies of thousands of animals called zooids that form in a hollow tube that can grow large enough for a human to fit through.

The sea creatures have a gene called luciferase that produces light and when it reacts with a luminous chemical, it sends the light up and down the tube, allowing it to see several meters in front of it.

They can also reproduce through asexual reproduction – effectively cloning themselves – or they can reproduce with a sexual partner.

A new study has found that pyrosomes, also called sea pickles, consume most of the energy in the ocean off the west coast of the US

Pyrosomes do not provide an adequate food source for other species because 98 percent of their waste ends up on the seafloor

The researchers looked at data from 80 groups of creatures, three feeding pools, five waste pools and two fisheries collected since 2014.

“Pyrosomes consume animals at the base of the food web and conserve that energy,” said Lisa Crozier, research scientist at NOAA Fisheries Northwest Fisheries Science Center and co-author of the paper.

“They take energy out of the system that predators need,” she added.

Pyrosomes can grow up to 20 meters in length and had not been seen for 25 years before 2014

Pyrosomes are not consumed as often as other creatures, such as jellyfish, and the study suggests that this “may be because they are harder to digest, offer lower energy content, or remain new to the food web so predators have not yet responded.”

According to the study, pyrosomes have long been considered “trophic dead ends” because they cannot serve as an energy source for other species, and how nutritious they are for other creatures that have consumed them in recent years remains unclear.

“That has an impact on the entire ecosystem… the pyrosome consumes energy that would normally have passed through multiple prey before ultimately ending up in a salmon,” study co-author Dylan Gomes said. The Seattle Times.

Pyrosomes are not consumed as often as other creatures, such as jellyfish, and the study suggests that this “may be because they are harder to digest, offer lower energy content, or remain new to the food web so predators have not yet responded.”

The 2013 marine heat wave, known as ‘the Blob’, increased water temperatures, allowing pyrosomes to thrive, while some fisheries closed as salmon, cod and Dungeness crab populations declined.

Scientists have speculated whether rising temperatures could be to blame for animals’ metabolisms increasing in warmer water, causing them to use more energy.

“You can think of it as more being consumed for the same amount of seafood produced,” Gomes said NewScientist.

Gomes said the study does not take into account factors that could affect declining marine life, such as declining oxygen levels caused by warming waters.

However, he added: ‘It is a first attempt to understand how marine heat waves are changing the ecosystems of the northeast Pacific Ocean.’

The team also compared other marine animals to the pyrosomes and found that they benefited most from the ecosystem, while other species such as jellyfish, cod, sardines, sea snails and other creatures missed out, causing their populations to decline.

While other creatures such as salmon pass on their energy source to feed larger animals, the study suggests this is not the case for pyrosomes, where 98 percent of their waste and residue accumulate in the seabed – called detritus pools.