Brits have always loved a fart joke! Henry VIII’s 800-year-old book contains a joke about an animal with ‘astonishing flatulence’

At first glance it seems like a profound moment from medieval history, stunningly captured with the finest pigment and gold leaf.

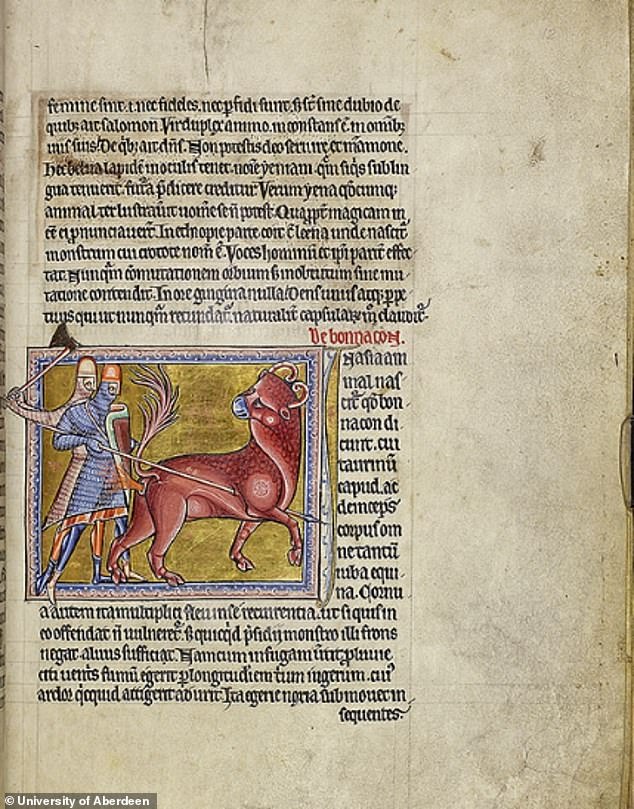

But on closer inspection, this lavish illustration from an 800-year-old book actually shows one of Britain’s first printed fart jokes.

The throwaway scene shows a fictional creature called the Bonnacon unleashing its “secret weapon”: an “amazing” strain of powerful flatulence.

While stabbed with a spear, the evil beast expels acidic gas and feces from its anus as a form of defense against two knights.

The comic drawing can be found in the Aberdeen Bestiary, a medieval manuscript kept at the University of Aberdeen that once belonged to King Henry VIII.

In the illustration, the fictional bonnacon expels acidic feces from his anus as a form of defense against two knights

The image has been rediscovered by satirist and Private Eye editor Ian Hislop in his search for Britain’s earliest jokes for a new podcast.

Hislop contacted Professor Jane Geddes of the University of Aberdeen’s School of Divinity, History, Philosophy and Art History, who is an expert on the Aberdeen bestiary.

‘This image in the Aberdeen bestiary is particularly explicit,’ Professor Geddes told MailOnline.

‘All the other animals in the book really have a certain moral attached to them, so you have to be frugal or hardworking.

‘But the bonnacon has no morals attached to him – he just shits, that’s what he does.

‘It is automatically funny for everyone from the age of four.

“There are certain fundamental things we still find funny and one of them is poop.”

What makes it even funnier, says Professor Geddes, is that the illustration is covered in gold leaf.

“It’s shiny gold, it’s a beautiful miniature painting, and then there’s poop.”

The full page in the Aberdeen Bestiary, a medieval manuscript kept at the University of Aberdeen that once belonged to King Henry VIII

Other illustrations in the book include the deceitful knight stealing a young cub from a mother tiger

Plus, one of the knights just stuck a spear through the beast, so emptying its powerful innards may be his final act of revenge.

Other illustrations in the book include a rogue knight stealing a young cub from a mother tiger.

As he escapes with the cub and is watched by the mother on horseback, the knight throws down a reflective glass ball.

The tigress is deceived by her own image in the glass and thinks it is her stolen cub.

There are also scenes of lions and panthers, elephants, dogs and goats, as well as fictional creatures such as the basil and the scitalis snake.

Bestiaries were illustrated animal books, some real and some mythological, used to convey Christian moral messages.

They were popular in the 12th and 13th centuries, but few were as lavishly produced as the Aberdeen version, which has been in the care of the university for almost four centuries.

Created in England around 1200 and first documented in the Royal Library of Westminster Palace in 1542, the Aberdeen Bestiary is one of the finest surviving examples of a medieval illuminated manuscript.

At some point it ended up in the English library of royal collections, probably selected by Henry VIII’s scouts during the Dissolution of the Monasteries sometime between 1536 and 1541.

The book is known as the Aberdeen Bestiary and was created in 1200. It includes stories about animals to demonstrate the key beliefs of the period

The Aberdeen Bestiary is one of the most luxurious ever produced, probably created for the enjoyment of many. In the photo a Basilisk is being attacked by a weasel

It has been in the care of the University of Aberdeen since 1625, when it was bequeathed to the university’s Marischal College by Thomas Reid, a former regent of the college and the founder of the first public reference library in Scotland.

Only recently did historians find hidden handwritten notes and dirty thumbprints from Tudor times in the margins of the book.

It is thought that the book was probably used for education rather than for the royal elite, according to Professor Geddes.

“Many of the words have little lines on them that could have been a guide to correct pronunciation when the book was read,” she said.

‘This shows that the book was designed for an audience, probably consisting of teachers and students, and that it was used to convey a Christian moral message, both through the Latin words and through striking illustrations.’

The new podcast, ‘Ian Hislop’s Oldest Jokes’, is here available to listen to on BBC Sounds.