Antarctic sea ice is falling to an ‘alarming low’ for the third year in a row, scientists warn

Antarctica’s sea ice has fallen to an ‘alarming’ low during the Southern Hemisphere summer, scientists have revealed.

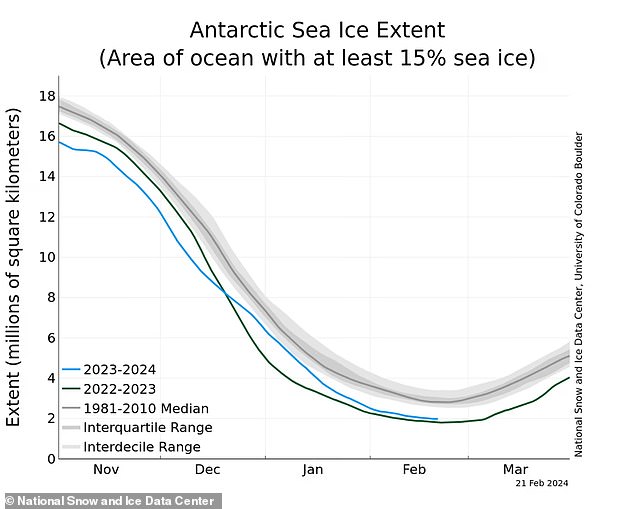

The ice surrounding Earth’s southernmost continent now measures less than 2 million square kilometers, or about the size of Mexico.

According to the US National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), this is the third year in a row that this figure has fallen below this threshold.

Less sea ice can threaten the habitats of penguins, seals and other Antarctic wildlife, and also contributes to global sea level rise.

Unfortunately, this also follows a record low for Antarctic sea ice in winter.

Antarctica’s ‘sea ice extent’ refers to the ice surrounding Antarctica’s coastline. Here the average extent of sea ice for the period 1981 to 2010 is highlighted in orange for this time of year – but in much of this area the ice is now ‘missing’

Sea ice plays an important role in maintaining Earth’s energy balance while helping keep the polar regions cool thanks to its ability to reflect more sunlight back to space. In the photo: sea ice in the water near Cuverville Island in Antarctica

Walt Meier, a senior researcher at NSIDC, said experts “don’t yet know the full reason” why sea ice is now at record lows, although “global warming could certainly be a factor.”

‘It appears that warm ocean temperatures are important, but other factors may also be at play, including wind patterns,’ he told MailOnline.

‘We only have 45 years of high-quality data, which may still not capture all the variability in Antarctic sea ice.

‘However, since 2016, Antarctic sea ice has largely been much lower than normal, sometimes reaching record depths.’

Professor Martin Siegert, a glaciologist at the University of Exeter, agreed that “we don’t know for sure” what causes it.

“It would be good to have a definitive answer, but it doesn’t really matter,” he told MailOnline.

“We certainly can’t afford to attribute this to variability as an excuse not to stop burning fossil fuels – that would be insane.”

Antarctica’s sea ice is critical because the ice reflects light from the sun, keeping the polar regions cool.

Without this ice cover, dark parts of the ocean are instead exposed, which absorb sunlight instead of reflecting it, which in turn warms the region and further accelerates ice loss.

Climate scientists continuously monitor the extent of sea ice through the seasons and compare its extent to the same months of previous years to see how it changes. Data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center recently showed that sea ice extent is lower than average since records began, regardless of time of year

According to NSIDC, the five-day average of sea ice cover fell to 768,343 square miles (1.99 million square kilometers) on February 18.

It then dropped further to 764,482 square miles (1.98 million square kilometers) on February 21.

This is still not as severe as the record-breaking minimum ice area of 683,400 (1.77 million square kilometers) set in February 2023.

However, looking at the broader picture, the three lowest years on record, according to scientists, have been the last three years.

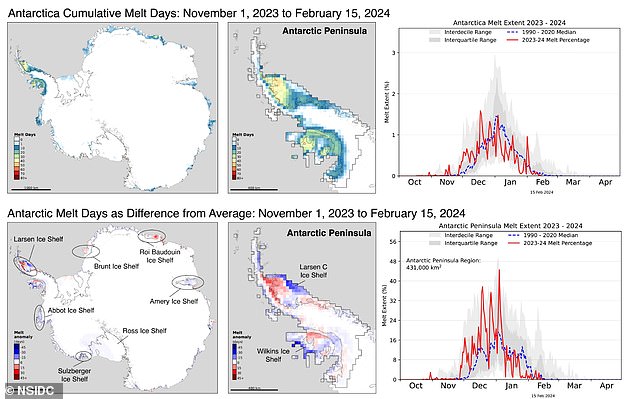

Ice sheet surface melt on the Antarctic Peninsula dropped abruptly in mid-January and remained low through February 15

Because it is summer in the Southern Hemisphere, most of the ice in Antarctica is currently estimated to be only 1 to 2 meters thick.

Dr. Ariaan Purich, a climate scientist at Monash University in Australia, thinks the ice is thinner than normal since it reformed after winter.

“It seems plausible, and thinner sea ice could melt faster,” Dr. Purich said the guard.

Antarctica’s ‘sea ice extent’ refers to the ice that surrounds Antarctica’s coastline, and does not include the ice that covers the landmass itself.

Due to colder temperatures, sea ice reaches its maximum extent in the Southern Hemisphere winter (July to September).

But temperatures rise gradually and reach a minimum during the Southern Hemisphere summer (December to February).

As in the Arctic, the ocean surface around Antarctica freezes in winter and melts back each summer. Antarctic sea ice (photo) usually reaches its annual maximum extent in mid to late September (winter) and reaches its annual minimum in late February or early March (summer)

Climate scientists continuously monitor the extent of sea ice throughout the seasons and compare its extent to the same months of previous years to see how it changes

So while there is a large variation in ice extent depending on the time of year, it is lower than the average since records began, regardless of season.

Last year, during the austral winter, NSIDC reported that sea ice levels in Antarctica were at a “staggering” all-time low for the time of year of less than 17 million square kilometers.

This is 580,000 square miles (1.5 million square kilometers) less than the September average – and equivalent to five times the size of the British Isles.

Ice melt in parts of Antarctica – including the Antarctic Peninsula – was also above average between mid-January and mid-February

In a recent blog post, NSIDC also said that weather conditions remained warm in central West Antarctica from January 15 to February 15, where air temperatures were 4°F (2°C) above the 1991 to 2020 average.

Meanwhile, ice on the Antarctic Peninsula – the part of the continent that sticks out like a tail – dropped abruptly in mid-January and remained low through February 15.

The rapid warming has already led to a significant southward shift and contraction in the distribution of Antarctic krill – a keystone species, campaigners say.

A recent Greenpeace expedition to Antarctica also confirmed that gentoo penguins are breeding further south due to the climate crisis.