I am part-Aboriginal. I am unapologetic about using this single word – but someone suddenly decided overnight we’re not allowed to say it

A prominent academic who calls himself “part Aboriginal Australian” insists there is nothing offensive about the word “Aborigine” and he will continue to use it.

Anthony Dillon, a well-known commentator on Indigenous affairs, said no one had been able to explain to him why the term was now considered insensitive.

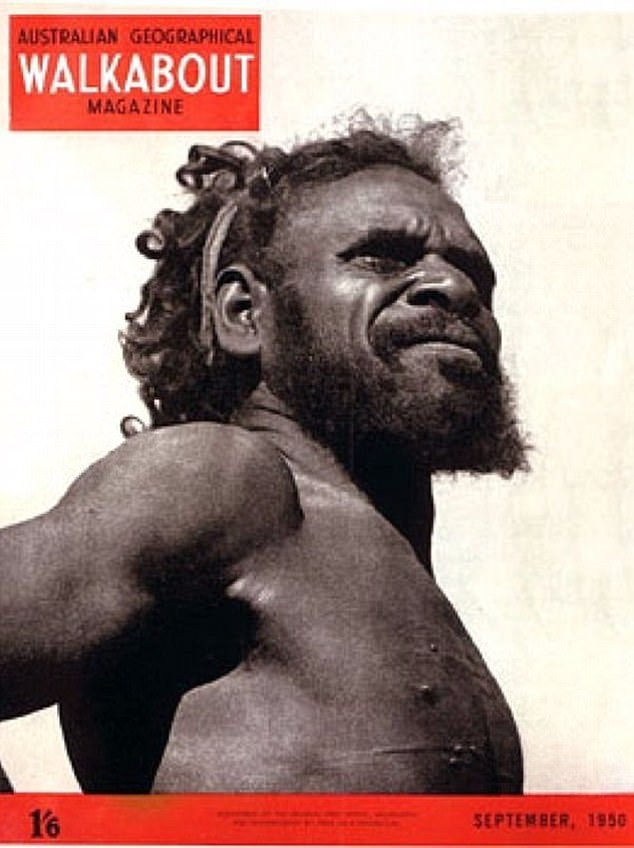

He believed that some Australians who identified as Indigenous might be uncomfortable that ‘Aborigine’ could conjure up an image of someone who was ‘clearly and unmistakably a full-blooded Aboriginal’.

“I don’t have a problem with the word,” Dr Dillon told Daily Mail Australia.

‘Twenty or thirty years ago that was fine, but then from one day to the next someone told you not to use that word. I said why?” and no reason was ever given.

Anthony Dillon, a ‘part Aboriginal Australian’ academic and commentator on indigenous affairs, insists that the word ‘Aborigine’ is not offensive. He is pictured with Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, the federal shadow minister for Indigenous affairs

‘It was similar to the term ‘part Aboriginal’; that was fine for years, but from one day to the next someone said, ‘Oh, that’s offensive.’

“Now I’m open to the reason, but no one has given me a reason yet.”

Human rights organization Amnesty International advises against calling someone an Aboriginal on its website, even if they are Aboriginal.

‘Aboriginal’ is generally perceived as insensitive because it has racist connotations from Australia’s colonial past and lumps people from different backgrounds together,” the report states.

‘If you can, try to use the person’s clan or tribe name. And when you’re talking about both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, it’s best to say ‘Indigenous Australians’ or ‘Indigenous people’.”

Dr. Dillon, an honorary fellow at the Australian Catholic University, said there was nothing offensive about calling someone an Aboriginal.

“I think it was just random,” he said. “Maybe ‘Aboriginal’ also conjures up images like the man on the two-dollar coin, things like that.”

Anthony Dillon believes some Australians who identify as Indigenous may feel that ‘Aborigine’ conjures up an image of someone like Bwoya Jungarai (above), who appears on the $2 coin, and that is not how they see themselves

Gwoya Jungarai, who survived the 1928 Coniston Massacre in Central Australia, is depicted on the coin with a traditional headband, flowing beard and tribal scars on his chest.

The image of Jungarai, or someone like him, may not fit with how the increasing number of light-skinned Australians who identified as Aboriginal saw themselves, Dr Dillon suggested.

Gwoya Jungarai appeared on both a postage stamp and the $2 coin

“We know that over the last 10 to 20 years, more and more people are identifying as Indigenous based on the fact that they have Indigenous ancestry,” he said.

‘I’m not saying they can’t do it. I’m just saying that we don’t need to change the language, or at least we don’t need to be told what language I can and cannot use.”

In the 2021 census, 812,728 Australians identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, up from 649,171 in 2016.

“A person can have one drop of Native ancestry,” Dr. Dillon said. ‘If they want to identify themselves, that’s their business. But I don’t see anything wrong with calling them Aboriginal.’

Dr. Dillon also believed that some people simply enjoyed causing offense.

“Because being offended means you feel important and people like to feel offended,” he said.

Human rights organization Amnesty International advises against calling someone an Aboriginal on its website, even if they are Aboriginal. ‘Invasion Day’ protesters are pictured in Sydney on January 26

‘They like to be gatekeepers. People want to be either the offended or the savior. The thought police.’

Dr. Dillon had no problem with language change and gave the example that he preferred to say ‘someone with diabetes’ rather than ‘a diabetic patient’.

“There’s a reason behind that,” he said. ‘We talk about the person, we don’t define him in terms of the disease he has.

‘But no one has been able to explain to me why the term Aboriginal is not allowed.

“Having said that, I will often say ‘Aboriginal people’ because I don’t go out to deliberately provoke. But I will say ‘Aboriginal’ every now and then and I won’t apologize for it.”

The Macquarie Dictionary defines an Aboriginal as ‘a member of a tribal people, the earliest known inhabitants of Australia’ or ‘a descendant of this people’.

It also warns that the word may be offensive and suggests using other descriptors.

“Some view the nouns Aborigine(s) and Aboriginal(s) as having negative, even derogatory connotations,” says de Macquarie.

Aboriginal people have increasingly identified themselves by language groups, using expressions such as ‘Bundjalung man’ or ‘Noongar woman’. Protesters gather in Melbourne on January 26

‘The use of Aboriginal as an adjective, forming nouns such as Aboriginal people, Aboriginal woman, Aboriginal Australian etc., is preferred by many.

‘The adjective Indigenous can be used to include both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

‘Indigenous Australians from certain regions of Australia are also sometimes referred to by names from indigenous languages.’

Aboriginal people have increasingly identified themselves by language groups, using expressions such as ‘Bundjalung man’ or ‘Noongar woman’.

The Creative Spirits website, which provides research material on Aboriginal culture, recommends using “First Nations people.”

“People have used many terms for the first peoples of Australia,” it says. “The previous terms were blatantly racist and remain offensive.

The Creative Spirits website, which provides research material on Aboriginal culture, recommends using “First Nations people.” Protesters are pictured in Adelaide on January 26

‘Then ‘Indigenous’ was very popular before the more politically correct ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ replaced it.

“But all these terms were coined by non-indigenous people. The new term now emerging in Australia is “First Nations people(s)”.

Creative Sprits says this term is preferable because Aboriginal people lived in Australia before anyone else and formed nations rather than small groups.

“Every nation, like every other nation on this planet, has its own culture, history and language,” it says. ‘The plural, nations, refers to the diversity of all nations in Australia.’

Creative Sprits dislikes “indigenous” because it “generalizes the cultures of the mainland and the cultures of the islanders into one, ignoring the many different cultures that exist.”