Nine million voted ‘No’ to the Voice. Now its most high-profile architect Thomas Mayo reveals what he REALLY thinks of them – and his message for every Australian

The public face of the ‘Yes’ campaign has called on Australians who voted ‘No’ in the Indigenous Voice to Parliament to push for better outcomes for Aboriginal people – even if they don’t want an advisory body added to the constitution .

Thomas Mayo, the most prominent leader of the Yes23 campaign after Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, told Daily Mail Australia he accepted the referendum defeat and understood that most Australians do not want constitutional change.

However, this is not the end of the story: he still believes that the majority of his fellow Australians want to improve the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

“I accept that a majority of Australians voted ‘no’, but that does not mean we will stop trying to improve the opportunities for our children to inherit a country reconciled with equal outcomes for Indigenous people, ‘ he said.

“I want those who voted No (and) who still want to close the gap for Indigenous people to reject the idea that No means ‘no progress.’

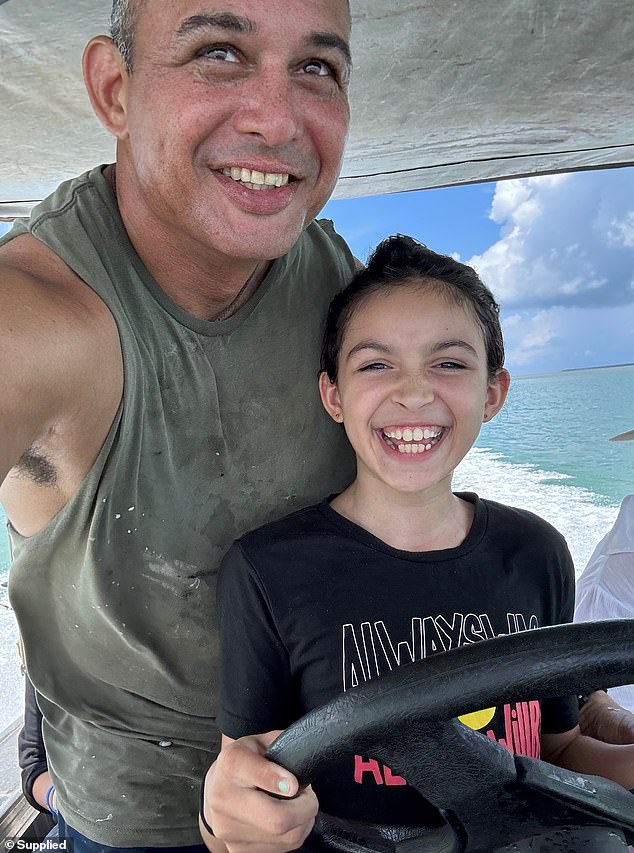

Thomas Mayo (pictured fishing in Darwin) has reflected on the defeat of the Voice referendum

“This is too important to worry about what happened in the referendum; we have to move forward.’

Mr Mayo stressed the importance of pushing for “better policies and legislation to close the gap” between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, adding that he still believes most ‘No’ voters do care about First Nations people care – even as they recoil at the idea of changing the Constitution.

“I don’t think the people who voted no on this issue don’t want progress, the vast majority of them,” he said.

“(We must) stop playing political games with the lives of indigenous people and just get on with the urgent work.”

Mr Mayo now believes it is crucial that the two sides in the bitter Voice debate talk to each other.

“I think a lot of No people are still interested in seeing improvement,” he said.

‘I think they have learned a lot from the referendum and are poorly informed.

After spending just 25 days at home last year, Mr Mayo is taking the opportunity to enjoy some family time (pictured with 12-year-old Ruby)

“I hope they keep looking and find out the truth behind these things: We don’t get free cars and we don’t get to hear all these things that people hear.

“We did not intend to take people’s backyards or farms, and the words for the constitutional amendment would not do that.”

Mr Mayo has called for the establishment of an Indigenous advisory body to the federal parliament, despite losing the referendum.

According to him, this is not a ‘requirement’, but simply ‘common sense’.

Before the referendum, a legally enshrined Vote was even proposed by the No campaign.

“At every opportunity, they (non-voters) should expect politicians to listen to indigenous communities about the solutions,” he said.

‘This is important. It remains common sense that they should do that.’

He said both major political parties have supported a legislative Voice for about a decade, despite the coalition opposing the Voice referendum.

‘Both have supported legislating the means to work with indigenous peoples, on the basis that there is general agreement that listening to the people about whom they make decisions is the best way to get things right ‘, he said.

Mr Mayo noted that a landmark that led to the referendum was the 2015 Kirribilli Declaration, made by 40 indigenous leaders – including No campaigner Nyunggai Warren Mundine – after they met with then Liberal Prime Minister Tony Abbott.

While he accepts that there will be no constitutionally anchored advisory body, one of Mr Mayo’s great regrets about the referendum is the fact that Australia is still has not joined the many countries that recognize indigenous peoples in their founding documents.

“We have lost that unique opportunity to take that step and catch up with the rest of the world,” he said.

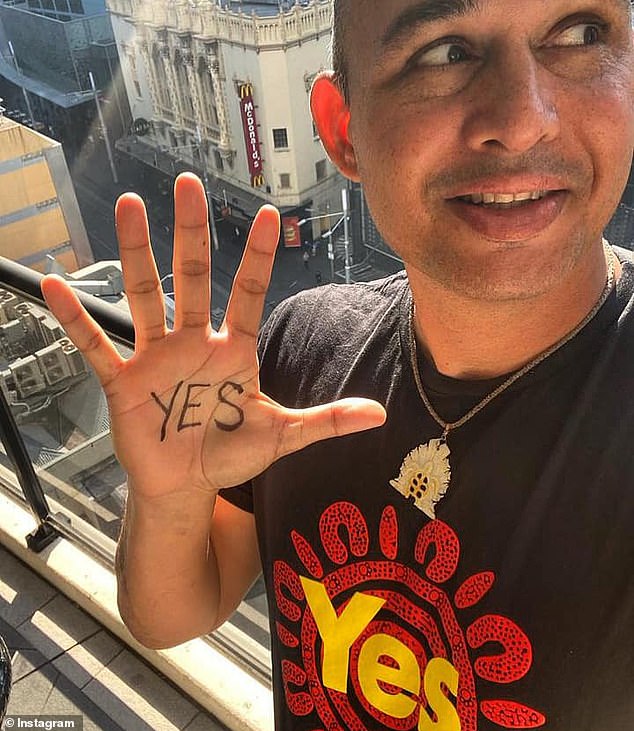

Mr Mayo (pictured centre) stands behind Prime Minister Anthony Albanese at a press conference in Canberra last year

On a personal level, Mr Mayo said he had no regrets about his role in the campaign, which saw him go from a little-known Northern Territory official at the Maritime Union of Australia to a household name..

‘I don’t regret it because it was a collective decision of ours to take that forward from the Uluru Statement (from the heart) and it was a rare opportunity that there was a government and a Prime Minister who listened to that request of a majority of indigenous people,” he said.

“I don’t regret it either, because I know that from the figures of the remote voting booths, where mainly indigenous people live and vote, there was a majority ‘Yes’.”

‘It was something the indigenous people wanted. It was something that would have been good for the indigenous people, and we had to try because this is an urgent matter.”

While he admitted that “there are always things” that could have been better during the campaign, he declined to perform a post-mortem on why the Yes case was rejected by more than 60 percent of Australians on October 14.

He said there had been many personal attacks against him, but he didn’t let them get under his skin.

“In the end, I knew what I did was the right thing to do and it was fair,” he said.

“I understood that people were trying to provoke a response from me that would be damaging to the campaign, which was ultimately just about giving people an advisory voice that would not have taken anything away from an Australian.

“That’s the one thing that kept me going every day. They couldn’t touch me because I knew what their strategy was, which was to try to get me to stop advocating. Intimidate.

‘I saw it happen not only to myself, but also to many, especially indigenous people, who spoke out in support of the referendum. That kept me going, because I knew it was right.

The Kaurareg Aboriginal and Kalkalgal, Erubamle Torres Strait Islander man has been granted extended leave from his union job and plans to spend the time writing a book about the road ahead for Indigenous issues at his home in Darwin.

Mayo spent almost 25 days on the road last year campaigning for Indigenous Voice

He will also be catching up on time with his family, after spending just 25 days at home last year while campaigning relentlessly for The Voice.

Mr Mayo has five children, three older and two aged 10 and 12.

“The young people missed me,” Mr. Mayo said.

Mr Mayo said although it was very humid in Darwin waiting for the wet season, this was his favorite part of the year.

He recently described taking a fishing trip with his 12-year-old daughter Ruby and son Will in a December article for the Saturday Paper.

“On a construction day like this there is barely a breath of wind,” he wrote.

‘The sea surface lies like foil on a baking tray in the oven. Among them are crocodiles, sharks and jellyfish.

‘The clouds provide no relief from the sun’s heat, and neither does the small canvas awning on the boat. The humidity makes the air feel like hot soup.’

‘Despite all the uncomfortable heat, this was what I longed for as I traveled around the country during the long and intense referendum campaign.’