England’s measles hotspots revealed in interactive map: Cases double in a year to highest level in 30 years as unvaccinated children are forced to isolate for three weeks

Unvaccinated children in the West Midlands are being forced to isolate for up to three weeks due to the region’s worst measles outbreak since the 1990s.

More than 300 cases have been identified since October, resulting in 50 children being admitted to Birmingham Children’s Hospital for treatment in the last month.

Health chiefs, who have already declared a ‘national incident’, blamed low uptake of the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

They urged parents to check that their children have had both doses of the jab or they risk becoming seriously ill from the virus and passing it on to others.

Children who have not been vaccinated and have been in contact with an infected person are forced to stay at home for up to three weeks to contain the virus.

MailOnline’s interactive map reveals the number of cases detected in each local authority in England, Wales in December.

The latest data from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) shows that there were 1,603 suspected cases of measles in England and Wales in 2023. This figure is more than double the 735 in 2022 and an almost fivefold increase compared to the 360 reported cases. in 2021

More than 300 cases have been identified since October. Fifty children needing treatment for the virus have also been treated at Birmingham Children’s Hospital (pictured) in the past month

In a letter to parents, Birmingham City Council warned that pupils who have not had the vaccine – given to children aged one year, followed by a second dose at three years and four months – will be told to isolate for 21 days if they are exposed to measles.

The warning, which was posted on January 4 as children returned to classrooms, read: ‘Anyone who has not been vaccinated and is exposed to someone with measles may be advised to isolate for three weeks.

This would disrupt their learning or working process and could happen repeatedly.’

The letter, sent by the council’s deputy director of public health, Dr Mary Orhewere, noted that GPs can give out catch-up doses of the MMR jab, which provides lifelong immunity against the three viruses it protects against.

Two doses provide up to 99 percent protection against measles, mumps and rubella, which can lead to meningitis, hearing loss and problems during pregnancy.

In addition, catch-up vaccination clinics for parents, staff and students will be held at schools across the West Midlands.

The three-week isolation advice was first issued by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) in 2019.

But concerns about low uptake and a rise in cases prompted councils, including some in London, to issue a reminder of the policy in recent months.

Under this leadership, children are banned from school and told not to mix with other children and those considered vulnerable – babies, pregnant women and children with suppressed immune systems. But they can still leave their homes for other activities.

Health chiefs say the three-week isolation, while disruptive, prevents measles from spreading among children – which could leave more seriously ill.

Measles is so contagious that nine out of ten children in a classroom without a shot become infected if only one classmate has the virus.

The UKHSA said it is issuing advice on a ‘case by case’ basis, following discussions between council officers and schools.

It said: ‘There have been children who have had to stay out of school because they had been in contact with a person with measles and had not been vaccinated.

“If they have had one dose they can stay at school, but if they have had neither they will be asked to stay away.”

It comes after Dr Naveed Syed, a consultant on communicable disease control at the UKHSA, based in the West Midlands, warned yesterday that he was seeing ‘more cases of measles increasing every day’.

He added: ‘The uptake of MMR in the region is far lower than necessary to protect the population, giving this serious disease an opportunity to gain a foothold in our communities.’

At least 95 percent of the population must be vaccinated to prevent outbreaks, guided by public health.

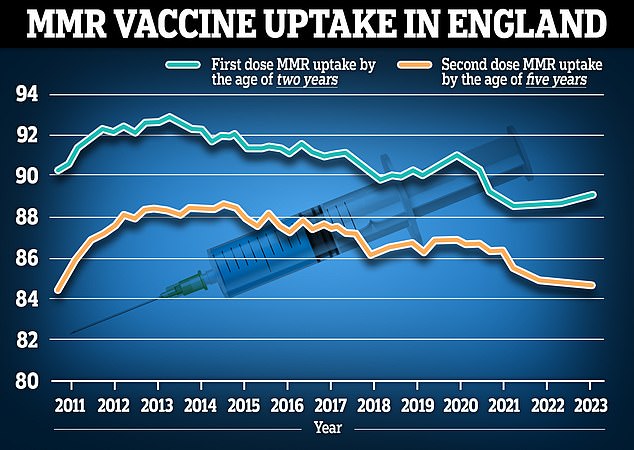

But nationally the percentage of five-year-olds fully vaccinated has fallen to 84.5 percent – the lowest in more than a decade. This trend is partly attributed to the rise of anti-vaxx attitudes.

However, experts have also pointed to the pandemic causing some children to miss out on routine vaccinations, as well as increasing pressure on primary care and a decline in health visitors.

The latest data from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) shows that there were 1,603 suspected cases of measles in England and Wales in 2023.

The figure is more than double the 735 cases reported in 2022 and an almost fivefold increase compared to the 360 cases reported in 2021.

The suspected cases are based on official reports from doctors who diagnose based on clinical symptoms.

Although laboratory tests later do not confirm it is measles, health chiefs warn that levels are clearly rising.

In England, 89.3 percent of two-year-olds received their first dose of the MMR vaccine in the year to March 2023 (blue line), compared to 89.2 percent the year before. Meanwhile, 88.7 percent of two-year-olds had both doses, up from 89 percent a year earlier

The latest NHS Digital also shows that up to four in 10 children in parts of England will not have had both MMR jabs by the time they turn five.

Only 56.3 percent of young people in Hackney, east London, were fully protected against measles, mumps and rubella in 2022/2023.

After Hackney came Camden (63.6 percent) and Enfield (64.8 percent).

Outside London, the lowest uptake rates for both doses among five-year-olds were recorded in Liverpool (73.6 per cent), Manchester (74.5 per cent) and Birmingham (75.1 per cent).

Measles, which usually causes flu-like symptoms and a rash, can cause very serious and even fatal health complications if the disease spreads to the lungs or brain.

One in five children who contract measles needs to go to hospital, while one in fifteen develops serious complications, such as meningitis or sepsis.

Acceptance of the MMR jab collapsed after research by the now discredited doctor Andrew Wakefield, who wrongly linked the jabs to autism.

Uptake of MMR in England was around 91 percent before the publication of Wakefield’s research, but fell to 80 percent in the aftermath.