Crashed and stranded in the Andes for 72 days with no food… so would you have turned cannibal?

SOCIETY OF THE SNOW

by Pablo Vierci (Constable £25, 384pp)

Few news stories have provoked as much and as heated public debate as the events of 1972, which became known as the “Miracle of the Andes.”

The story, now sensitively told by Pablo Vierci in Society Of The Snow (and on which this week’s Netflix film of the same name was based) is almost too terrible to imagine.

On Friday, October 13, a twin-engine Fairchild passenger plane took off from Carrasco International Airport in Montevideo, Uruguay, bound for Santiago.

On board were the Old Christians Rugby Club, alumni of a local Catholic school, along with several family and friends. The boisterous young men were in high spirits as they flew over the peaks of the Andes on their way to a match in Chile. And then they encountered catastrophic turbulence.

The plane crashed into a huge air pocket. It crashed into a rock wall and split in two. Some passengers were ripped from the plane, others were crushed under metal.

Life or death: Netflix drama Society Of The Snow recreates ‘Miracle of the Andes’ crash

The tail shot off in one direction, while the main fuselage holding the passengers “landed hard on the mountain and began zigzagging down the slope,” Vierci writes.

It came to rest – part coffin, part cocoon – on a glacier called the Valley of Tears.

“During the crash, 16 people were killed and 29 survived,” Vierci noted. “Eventually those numbers turned around.”

That anyone got off the mountain alive was indeed a miracle, but a miracle full of horror: for 72 days the stricken passengers survived by eating the bodies of their dead friends. Since then, people have wondered, ‘What would I have done?’

The crash and its horrific aftermath have been recounted in numerous books, most notably Alive by Piers Paul Read.

While Read crafted a story of fortitude, Vierci takes a philosophical stance, analyzing group dynamics and what he calls a “pact of mutual self-surrender”: the passengers’ agreement to donate their bodies for sustenance when they die.

The book, originally published in Spanish in 2008 and now translated to coincide with this week’s Netflix adaptation, oscillates between chapters that follow the drama chronologically and sections with individual statements from survivors.

Two would play a central role in the story: Roberto Canessa, a compassionate young doctor in training, and Nando Parrado, a resourceful 22-year-old business student. Both understood that ‘in the society of the snow the rules were completely different from those of the society of the living’.

The other survivors are photographed cheering at the moment of their rescue

Several factors played in the passengers’ favor: they were young and fit, there were medical students on board, they had religious beliefs and a strong family background. In short, they had the basis for hope.

But their confidence evaporated beneath the grind of subzero temperatures lurking in the wreckage – “we were living in a freezer” – with festering injuries and few signs of rescue.

Crucially, within a few days they realized there was nothing to eat or hunt at that altitude. The only source of food lay in the bodies frozen in the snow.

On the eighth day the first strips of meat were cut. Canessa recalls that the decision was ‘a leap into the void’, but remains no-nonsense about the cannibalism:

‘First we started eating the muscles of the cadavers, later we were forced to follow the organs, until finally we had to crack open the skulls with an ax to get to the brains.’ That would be their diet for two months.

The calamities continued. On the night of October 29, the hull was hit by an avalanche, killing eight people and leaving others trapped under snow for several days.

There were other low points: two expeditions from the glacier ended in failure, and when a radio was found in the wreckage, they learned that the searches had been halted. They were all believed to be dead.

In a last-ditch effort to seek help, Canessa and Parrado trekked over the peaks to Chile for ten days. When they finally encountered a muleteer on the other side of a river, they knew they had been saved.

Survivors: Carlos Paez Rodriguez, Nando Parrado and Roberto Canessa at the closing ceremony of the 80th Venice International Film Festival in September 2023

They threw him a message tied to a rock. It started: ‘I come from a plane that fell in the mountains.’ The rescue helicopters were quickly on their way.

Vierci provides gruesome details: a passenger operates on his own gangrenous leg; a rugby ball becomes a bedpan; human flesh is cooked on a griddle made from the back of an airplane seat.

Then there is the ironic fate of Tito Regules, the only boy who missed the flight. Tito had partied and slept the night before. It saved his life. Twenty-one years later, he fell asleep at the wheel of his car and died in an accident.

Graziela Mariani, who happily sat down to attend her daughter’s wedding, died on the mountain. There was a domino effect of trauma.

When they returned, when the truth came out about what they had eaten to survive, the world gagged. One newspaper published a photo of the fuselage that clearly showed a half-eaten human leg among the rubble. The headline read: ‘May God forgive them!’

But the survivors’ families were resolute in their support. These were not cannibals, they claimed, but simply sons and brothers who had done what was necessary to get home. In endorsing that distinction, Vierci’s book is a triumph of empathy.

Vierci also describes a complicated – but inspiring – ripple effect from the disaster, which continues to this day. Half a century later, there are about a hundred children and grandchildren for these sixteen young men.

And while the book’s back-and-forth structure is frustrating, the approach allows for valuable first-person accounts from all survivors, including those who have not spoken publicly before.

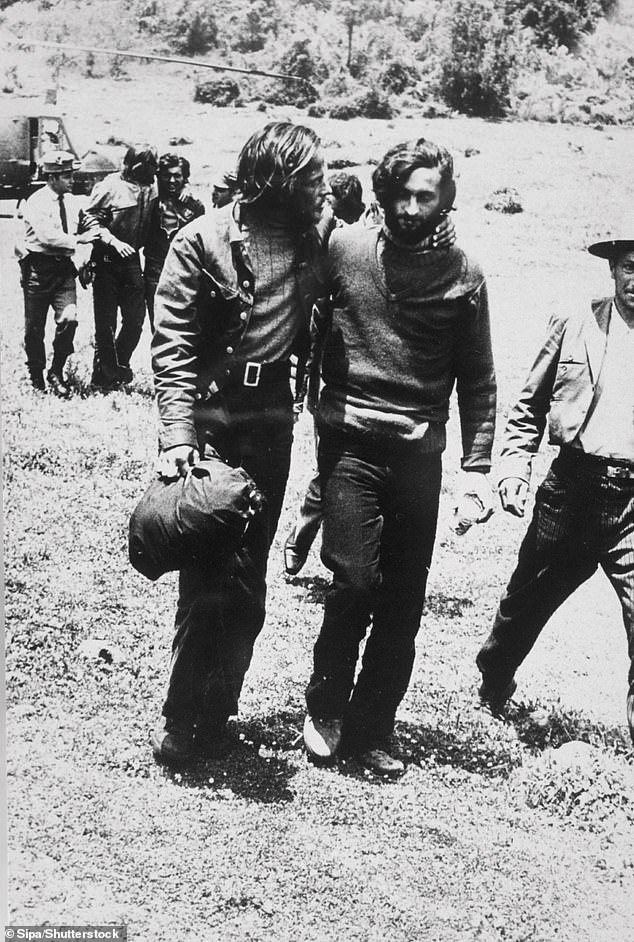

A rescue worker assists one of the survivors. The passengers were stranded in the snow in the Andes for 72 days

Some became successful businessmen, architects and doctors, others struggled to overcome their setbacks.

‘What were we? A group of unhappy young boys,” says Canessa.

‘What are we? A group of grown men looking for a reason for the great tragedy that has happened to us.’

Whether the ‘society’ Vierci describes is a product of retrospective and poetic framing, or an accurate image of a group making collective decisions, is questionable.

What is irrefutable, however, is that he succeeds in evoking readers’ compassion and understanding for those who have endured the intolerable and then moved on with their lives.