Iceland's volcano finally explodes with a primal roar and a giant fireball after thousands are evacuated from their homes, writes DAVID JONES

One moment the live webcam showed a desolate scene: a rocky snowy landscape against a moonless black sky. Then, with a primal roar that could be heard 40 miles away, a huge orange ball rose on the horizon, like an unearthly midnight sun.

Within seconds it seemed to transform into a series of giant Roman candles spewing glowing sparks high into the darkness.

And as more and more of these enormous columns of flame rose, the southwestern tip of Iceland was dazzled by a belated fireworks display, the awesomeness of which we have rarely seen.

The clocks on the video cameras that had been monitoring the Reykjanes Peninsula since late October, when a wave of underground rumbling warned of an impending volcanic eruption, had settled on 10:17 pm on Monday – and after six weeks of false dawn it was the Land of Fire and Ice lived up to its name.

As I stared into the fissures that had opened in the roads running through the evacuated town of Grindavik in mid-November, I had felt safe enough and could never have imagined the instantaneous force of 1200 degree Celsius magma fountains pouring into crevices below me layers.

Local residents see smoke rising as lava turns the night sky orange after a volcanic eruption on the Reykjanes Peninsula

Emergency workers and scientists in an Icelandic Coast Guard helicopter fly over a volcanic eruption

A volcano spews lava and smoke as it erupts north of Grindavik

An Icelandic Coast Guard helicopter flies over a volcanic eruption on the Reykjanes Peninsula

Watching them blast off at rocket-like speed yesterday, just two miles from where I was reporting that day, made me realize how lucky (and perhaps reckless) I had been.

But not nearly as happy as the 3,400 inhabitants of the fishing port. Just hours before the fireworks started, local police – believing the danger of an eruption had passed – insisted they be allowed to return to their homes for the Christmas holidays.

'The police thought it was safe, but civil protection was not really on the same page. They didn't want people to go back to Grindavik before Christmas,” Lovissa Mjoll Gudmundsdottir, a natural hazards specialist at the Icelandic Meteorological Agency, told me yesterday.

“We were supposed to have a meeting today to discuss it, but that's obviously not going to happen now.”

Last night Grindavik, with its neat wooden chalets and fish processing plants, remained mercifully untouched by the ribbons of golden lava that fanned out like filigree chains from the main fault line, two and a half miles long.

People view the volcano on the Reykjanes Peninsula in southwestern Iceland

A drone photo shows lava spewing from the volcanic eruption site

Lava flows on a hill near Grindavik on Iceland's Reykjanes Peninsula after a volcanic eruption on Monday evening

A drone photo shows lava spewing from the volcanic eruption site

People view the volcano on the Reykjanes Peninsula in southwestern Iceland, which erupted after weeks of intense earthquake activity

A team of scientists work at the edge of a volcanic fissure as lava spews during a volcanic eruption, near the town of Grindavik, on the Reykjanes Peninsula

However, given the unpredictability of volcanic eruptions of this magnitude and magnitude, none of the experts were foolhardy enough to predict with any certainty that the city would be spared.

“The best outcome will be if the eruption is short-lived and the lava flows away,” said Ms Gudmundsdottir, a graduate in volcanology from the University of Bristol. “The worst part is that it takes a long time.”

It could then threaten not only Grindavik but also the nearby geothermal power plant, she said.

Because it powers much of southern Iceland, authorities must hope the lava flow won't topple the protective wall they hastily built around it.

The more immediate danger comes from clouds of sulphurous gas seeping from the fissures, which last night moved closer to Reykjavik, 50 kilometers from the eruption zone, potentially endangering the health of elderly and vulnerable members of the 122,000 population.

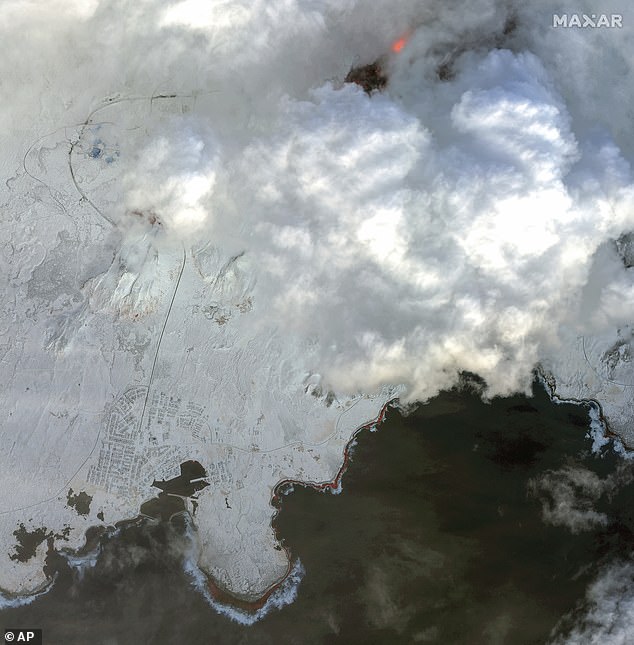

This satellite image from Maxar Technologies shows a close-up color infrared image of volcano and lava in Iceland on Tuesday

A rescuer walks in an area near a volcanic eruption, near the town of Grindavik

People view the volcano on the Reykjanes Peninsula in southwestern Iceland

Scientists from the University of Iceland take measurements and samples while standing on the ridge in front of the active part of the erupting fissure of an active volcano in Iceland

Smoke fills the air during a volcanic eruption, near the town of Grindavik

Members of a rescue team gather in an area close to a volcanic eruption

A team of scientists work at the edge of a volcanic fissure as lava spews out during a volcanic eruption

This satellite image from Maxar Technologies shows a color infrared view of Grindavik and lava from a volcano in Iceland

A rescue worker walks in an area near a volcanic eruption in Iceland on Monday

With Iceland's international airport, Keflavik, only ten miles away, flights were delayed for several hours yesterday, and the misery of British holidaymakers was compounded by an air traffic controllers' strike.

However, it is hoped the disruption will be short-lived as this is a different type of volcano to Eyjolfsdottir, which sent ash clouds across the North Atlantic in 2010, causing flights to be canceled or diverted for weeks.

Similar chaos will only occur if the eruption spreads across the coast and the emissions mix with seawater, experts say.

After causing an initial panic attack, the mesmerizing river of fire that spreads across the peninsula is fast becoming Iceland's biggest tourist attraction, more spectacular even than the Northern Lights and the Blue Lagoon.

Hundreds of tourists ignored official warnings to stay away and headed to the closed area yesterday, climbing hills to find the best vantage points. Hotels expect an influx of visitors in the coming days.

The atmosphere of excitement was captured by American holidaymaker Donald Forrester III. “It's just something out of a movie!” he cooed.

Maybe so, but as they watch the tongues of boiling orange lava lick the edges of their quaint town, the residents of Grindavik will be praying that the plot of this fire-and-brimstone blockbuster has a happy ending.