You looking at me? Mice can recognise themselves in the mirror – a key indicator of self-awareness, study finds

Spending long hours in front of the mirror may be a sign of vanity in a person.

But for mice, it may be a sign of self-awareness.

Just like humans and chimpanzees, mice can recognize their reflections in a mirror, according to a team from the University of Texas.

The scientists found that mice that were painted with white ink were able to see themselves in the mirror and try to clean themselves.

This means that the mice pass the “mirror test” – a criterion often thought to be a sign of self-awareness or awareness in animals.

The researchers found that mice that had been socialized and accustomed to mirrors were able to pass the “mirror test” – which is often thought of as a sign of self-awareness.

The researchers drew the heads of the mice with white ink to see if they could recognize their reflections in the mirror

In this study, the researchers anesthetized several black mice and painted their heads with different sized spots of white ink.

The mice were then placed in front of a mirror.

The researchers' observations revealed that mice with white markings spent more time grooming in front of a mirror, indicating that they had the ability to recognize themselves.

However, this was only the case under specific circumstances.

The mice only attempted to remove the ink when the stain was fairly large and when it was a different color from their fur, indicating that they were actually seeing something different about their appearance.

They also tried to clean the ink only if they had spent time around mirrors in the past and had been raised around mice that looked like them.

Black mice raised around white mice appeared to lose the ability to recognize their own reflection, suggesting that socialization plays an important role in the development of self-image (stock image).

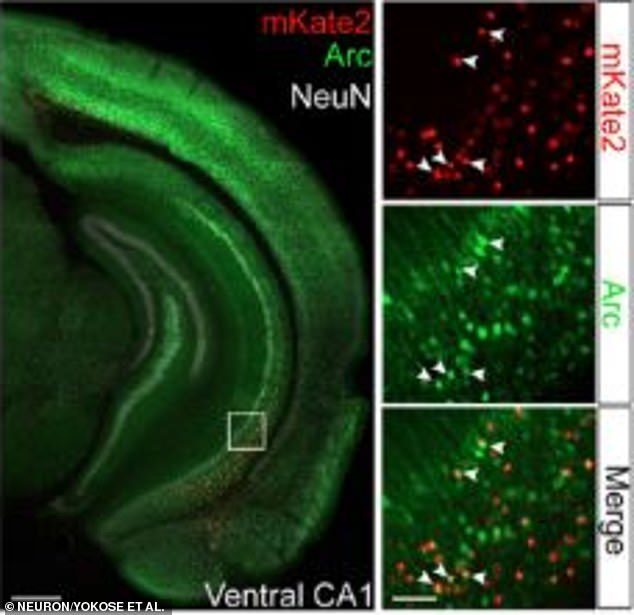

This image shows neurons in the hippocampus that scientists believe play an important role in the development of self-image

For example, only black mice that have grown up around other black mice appear to have the ability to recognize their own reflections.

Black mice that were isolated after weaning or raised in the company of white mice did not attempt to remove the marks from their heads, even when they were the right color and size.

The researchers say this proves that self-recognition and self-awareness must have a social component.

To further understand this effect, the researchers used brain scans to analyze the animals' brains while they looked in the mirror.

The scans revealed that a group of neurons in the hippocampus – a structure deep in the brain – were activated when the mice saw themselves in the mirror, as well as mice that looked similar.

Mice in which this area was deactivated were unable to recognize themselves.

Researchers suggest that without socialization. These neurons fail to develop, resulting in a lack of self-recognition.

Lead researcher Takashi Kitamura, from the University of Texas, said: “To form episodic memory, for example, for the events of our daily lives, brains form and store information about where, what, when and who, the most important element being subjective or situational information.

The authors say this does not prove that mice are self-aware, but it does show that they have the ability to recognize themselves

The mirror has been previously tested It is used to assess consciousness in a number of different animals, including chimpanzees, dolphins and elephants.

However, the researchers are careful to say that this does not prove that mice are self-aware.

Instead, what the data show is that mice have the ability to recognize themselves under certain conditions.

Lead author John Yukos, from the University of Texas, said: “The mice required significant external sensory cues to pass the mirror test, and we have to put a lot of ink on their heads, and then the incoming tactile stimulation enables them to ink in some way.” Animals can detect ink on their heads through the reflection of a mirror.

“Chimpanzees and humans don't need any of these extra incentives.”

This research was published in the journal nervous cells.

(tags for translation) Daily Mail