Super fungus infections rise to highest levels ever in parts of US amid fears about deadly strain that’s becoming resistant to drugs

Health officials in Nevada are sounding the alarm about a massive spike in cases of a “super fungus” that is also spreading nationwide.

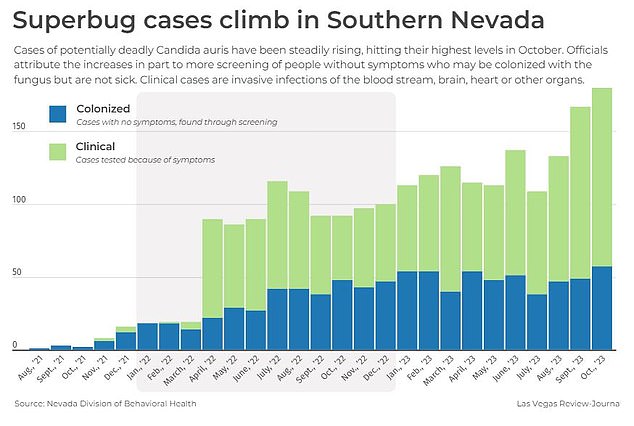

In October alone, nearly 200 people in southern Nevada tested positive for Candida auris, known as C auris, a microscopic strain of yeast that can cause infections in the bloodstream, brain, heart or other organs. That is more than double the number in 2021.

Nevada health officials are calling on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for more resources to address the growing problem — including training staff to recognize the infection.

Meanwhile, there are growing concerns nationally about the rise of C Auris, with cases having more than tripled in recent years.

Nevada had the highest number of cases in the US last year with 384. Next is California with 359 cases and Florida with 349.

Sharon McCreary (left) with her mother Lorrie McCreary (right) at an MLB baseball game in 2017. Lorrie died after contracting Candida auris from a hospital last year

Candida auris, known as C auris, is a microscopic strain of yeast that has become widespread in healthcare in recent years, killing up to a third of people who become infected with it.

C auris emerged more than ten years ago simultaneously in hospitals in India, South Africa and South America. Researchers don’t know why, but speculate that climate change could have played a role.

Fungi typically cannot tolerate the warmer temperatures of the human body, but scientists think C auris may have adapted to survive in a warming environment.

Another theory proposed in 2019 was that C auris may have existed as a plant fungus that had adapted to exist in both salt water and warmer temperatures due to global warming.

The type of plant would have been a saprophyte: a plant that has no chlorophyll and instead gets its food from dead organic matter.

Researchers at the University of Texas speculated that it could then be transmitted by birds from salt marshes around the world to rural areas where birds and people often come into contact.

Most transmission occurs in healthcare facilities, especially among residents of long-term care facilities or among persons with indwelling equipment – such as catheters, tracheostomies or wound drains – or via mechanical ventilators. WHY??

The fungus can enter the bloodstream and spread throughout the body, leading to potentially fatal invasive C auris infections, such as in internal organs. HOW DOES IT INFECT?

The fungus kills more than one in three people with invasive C auris.

Healthy people don’t normally get sick, but among the vulnerable it can be a death sentence.

In October last year, the World Health Organization (WHO) warned that fungal infections were becoming a ‘major threat’ to public health.

Dr. Hanan Balkhy, WHO Deputy Director-General for Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), said: ‘Fungal infections are emerging from the shadows of the bacterial antimicrobial resistance pandemic, growing and becoming increasingly resistant to treatments, becoming a public health problem worldwide . .’

Fears of widespread infections have increased as C auris is becoming drug resistant and there is currently no vaccine to prevent the infection.

In October, there were 57 new clinical cases of the deadly fungus in Southern Nevada that can infect a person’s bloodstream, brain, heart or other organs.

In the same month, about 123 cases of colonization, in which people have the fungus in the folds of their skin, which cannot be seen with the human eye, were also reported. They do not get sick, but can still spread the pathogen.

Since the first local cases were reported in August 2021, there have been nearly 2,300 total cases in Southern Nevada.

Last year, Southern Nevada was hit by the worst outbreak of C auris in the US, with HOW MANY AS A % OF FACTS CASES AMONG THE NATIONS THAT COME FROM THIS ONE SMALL REGION

In March, the American College of Physicians (ACAP) said the emergence and spread of C auris was “concerning.” The number of cases in America more than tripled between 2020 and 2021, from 1,310 in 2020 to 4,041 in 2021. Multidrug-resistant strains also became more common.

There are signs that it is still rising

Sharon McCreary, 61, previously told DailyMail.com that her mother Lorraine, 86, suffered a fatal stroke last summer after contracting the microscopic yeast strain Candida auris.

It is believed that she, like a growing number of Americans every year, contracted the infection in a hospital – where the fungus is becoming increasingly common.

Lorrie, as she was known to friends and family, was admitted in June with pneumonia, not unusual for the later stage of her life.

But just as she began to recover, her condition quickly deteriorated and doctors performed a barrage of tests to find the cause.

She was diagnosed with C auris, which kills up to half of people who become infected with it. Doctors believe she contracted the fungus through oxygen tubes.

It spreads from patient to patient through direct contact or through contaminated surfaces where it can lurk for weeks.

The infection was the start of a fatal chain of events for Lorrie, with the C auris worsening into sepsis and kidney failure, eventually leading to a fatal stroke.

Mrs McCreary told DailyMail.com that her mother Lorrie would not have died in June 2022 if she had not contracted C auris.

Lorrie had high blood pressure and arthritis, but was relatively healthy for her age.

She fell over twice in one day at her home and had to be rescued by the fire brigade.

The next day, Lorrie fell again. Her nurse took her to Baycare St Anthony’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Florida on June 10, 2022.

In the hospital, Lorrie was diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia, had a fever, was dizzy and weak, which caused her to keep falling.

At first things seemed to be going well for Lorrie. After a week, doctors called Mrs. McCreary and said her mother was doing better and that they were moving her to the rehabilitation unit.

But two and a half days later, Mrs McCreary received another call saying doctors had transferred her back to hospital.

The nurse told Mrs. McCreary that her mother had tested positive for C auris, which they discovered during routine blood tests.

Mrs McCreary said: ‘I’d never heard of C auris. I immediately went online to look it up and the Centers for Disease Control has a whole web page about it.

“I read it, looked at my husband and said, ‘This kills 50 percent of the people who get it.’ I just had this fear, and it was a legitimate fear.”

‘My mother just couldn’t get better. It was like a domino effect for her. The Candida auris was preventing her from getting over the other things.”

Lorrie also developed sepsis in the C auris. If the C auris yeast enters the bloodstream, it can cause an infection. The body may respond with sepsis, which can be life-threatening.

Sepsis occurs when chemicals released into the bloodstream to fight an infection cause inflammation throughout the body. This can lead to multiple organ systems being damaged and disabled.

Symptoms of sepsis include difficulty breathing, low blood pressure, increased heart rate, and mental confusion.

HOW IS C AURIS TREATED?

C auris could have jumped on humans during activities such as farming, and eventually in hospitals and health care systems as people migrated to cities.

A research team in India pointed out that C auris originated in a tropical wetland and acquired resistance to fungi after coming into contact with humans.

The first case was reported in 2009 after it was found in the ear discharge of a 70-year-old female patient at the Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital in Japan.

There are approximately 1,500 species of yeast, which are single-celled fungi. They are found worldwide in soil and on plants. Hundreds of varieties are used to make bread, beer and wine, among other things.

Some yeasts are dangerous pathogens to humans and other animals, especially Candida albicans, of which C auris is a type.

Transmission is largely driven by a lack of infection prevention and control practices in hospitals.