Healthy cocaine users could still be at serious risk after man, 34, suffered deadly blood clots from occasional drug use

You don’t have to be a cocaine addict to be at risk for serious health problems from using the drug.

A case report of an otherwise healthy patient using a certain amount of cocaine increases a person’s risk for seizures, heart failure, and serious lung damage.

A 34-year-old man arrived at a Wisconsin hospital with breathing problems and a life-threatening blood clot in a case that baffled doctors for days until it turned out the patient was an occasional cocaine user.

The man arrived at the emergency department with severe shortness of breath that had gradually gotten worse over a month, a high heart and breathing rate, high blood pressure and extreme anemia – a condition in which the blood does not contain enough healthy cells.

Scans of his chest and pelvis revealed this was the case severe blood clots in his lungs which had originated in his leg and migrated through his veins.

His was the third known case of severe blood clotting in the lungs due to cocaine use, although he is the first with a case that could not be linked to underlying health problems or a family history of clotting disorders.

Regular cocaine use has been shown to increase blood pressure, putting extra strain on the heart, which then has to work overtime to pump blood. CT scans of his chest revealed a severe pulmonary embolism, the term for a serious blood clot in the pulmonary arteries, as well as fluid buildup in his lungs, indicating pneumonia.

The patient, who was treated at the Mayo Clinic in La Crosse, Wisconsin, came to the hospital with an extremely pale complexion and difficulty breathing.

His temperature was normal, but his heart rate was very high: 115 beats per minute. A frequency above 100 at rest indicates a problem.

His breathing rate of 24 breaths per minute was also higher than the normal range of 12 to 18.

His blood pressure was high: 155/101 mmHg, compared to a healthy blood pressure of 120/80 mmHg, indicating that each heartbeat was putting very high pressure on the walls of his heart, which was working overtime to a dangerous degree.

The man’s hemoglobin level – the main component of red blood cells that carries oxygen throughout the body – was 0.56 grams per deciliter (gm/dL). This is approximately 28 times lower than the normal range of 14 and 17.5 g/dl.

When these levels fall below a healthy range, a condition known as anemia can occur, which causes people to feel fatigued, short of breath, and have an irregular heartbeat.

However, all his abnormal test results were just the beginning of problems for the patient, who is not mentioned in the case report.

Scans of his chest showed a severe pulmonary embolism, the term for a dangerous blood clot in the pulmonary arteries, as well as fluid buildup in his lungs, indicating pneumonia.

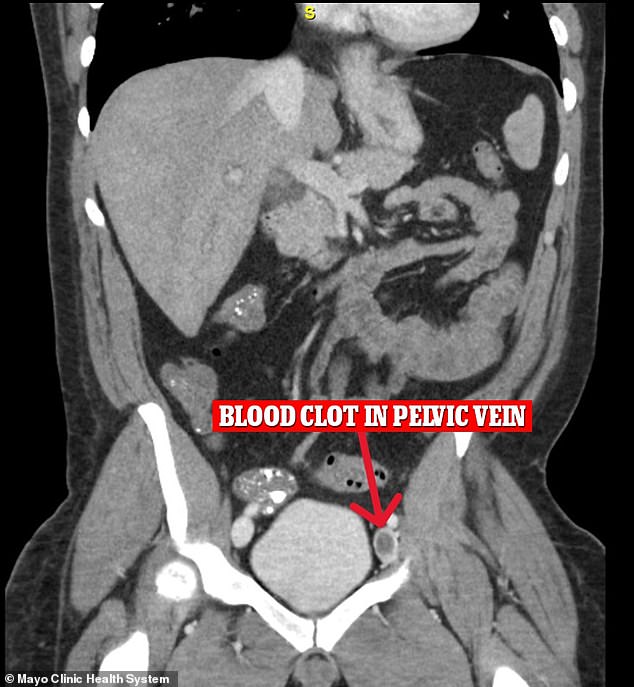

An additional scan of the man’s pelvis revealed that he also had a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), a blood clot that breaks free from a vein in the leg or pelvis and travels through the body to the lungs. DVT is a common cause of pulmonary embolism.

He was quickly transferred to the intensive care unit, where an ultrasound showed that the walls of his heart were enlarged and part of his heart was working harder to pump blood to his lungs because of his clot.

On day five, the man showed high levels of liver enzymes, or proteins that speed up various processes in the body. High levels are usually a warning sign of liver damage due to a lack of blood flow, but doctors said that “his presentation was inconsistent with this diagnosis.”

In addition, an ultrasound and MRI of his liver revealed “unremarkable” findings.

Other tests for autoimmune diseases and infections came back negative, the doctors added.

An additional CT scan of the man’s pelvis also revealed deep vein thrombosis (DVT), a blood clot that has broken free from a deep vein in the leg or pelvis before traveling to the lungs.

Although he initially told doctors that he was not using illegal drugs, on day eight of his hospital stay the man admitted that he had a habit of snorting cocaine once every one to two weeks when his parents were not around.

He had last taken the drug five days before going to the hospital.

His failure to admit he was using cocaine, “especially in the presence of his parents,” posed a significant barrier to doctors trying to diagnose him.

They said: ‘The patient’s reluctance to discuss drug use habits, especially in the presence of his parents, resulted in delayed detection of drug use through self-reported data, rendering urine and blood drug tests ineffective.

‘Moreover, this information was only discovered later; therefore, it was not feasible to check for adulterations in the blood or urine and to determine which tests to use for them.”

The patient eventually improved and he was sent home on antibiotics and supplemental oxygen for three to six months.

Doctors advised him against future cocaine use.

In the US, cocaine led to almost 25,000 deaths in 2021, and those numbers are rising. Nearly more than 19,400 cocaine overdose deaths were recorded in 2020, up from around 15,800 in 2019.

A government survey released in 2021, according to the most recent data, found that approximately 4.8 million Americans aged 12 and older had used cocaine in the previous twelve months.

And approximately 1.4 million Americans suffer from cocaine use disorder.

Researchers say this case report shows that doctors need to create a judgment-free space that encourages their patients to be honest, even about illegal drug use.

Experts claim that no amount of cocaine is safe, even when taken sparingly.

Portuguese and Brazilian doctors reported in 2020 that while chronic cocaine use has been shown to be highly toxic to the brain with a high risk of death, the dangers of ‘recreational’ use, which can lead to addictive behavior, are often overlooked.

Researchers said: ‘This stems in part from the belief that exposure to low doses of cocaine carries no risk of brain damage.

‘A single low dose of cocaine, which did not alter exercise behavior and brain metabolism, has the potential to cause structural neurological damage.

‘There is no safe dose for cocaine exposure. Structural changes in the brain should be taken into account regardless of the dosage used.”

Although a robust body of literature exists on acute high-dose cocaine, as well as cocaine addiction scenarios, an integrated analysis of behavioral, metabolic, and structural brain changes associated with acute low-dose cocaine is lacking.

Regular cocaine use has been shown to increase blood pressure in the lungs, putting extra strain on the heart, which then has to work overtime to pump blood. This could lead to heart failure in the future.

Inhaling cocaine through the nose also causes extensive damage to the mucous membranes and nasal passages, leading to lesions in the upper respiratory tract.

Snorting the drug also worsens asthma and causes spasms in the muscles lining the lungs, potentially leading to respiratory failure.

Cocaine is a Schedule II drug in the US, the same category as meth, oxycodone, Adderall, Ritalin and Vicodin. It is usually smuggled into the country from outside and is derived from the coca plant grown mainly in Colombia, Peru and Bolivia.