Investor who bought Wyoming coal mine sight-unseen for $2M learns it may contain $37BILLION worth of ‘rare earth’ minerals used for semiconductors, missiles and solar cells

- Randall Atkins, 71, bought the Brook Mine 12 years ago, but it wasn’t until years later that researchers discovered the soil contained rare earth elements

- Its rare earths can sell for more than $1 million per tonne

A 71 year old investor who bought an old one Wyoming The coal mine, which has remained invisible for $2 million, has learned it could contain $37 billion worth of “rare earth metals.”

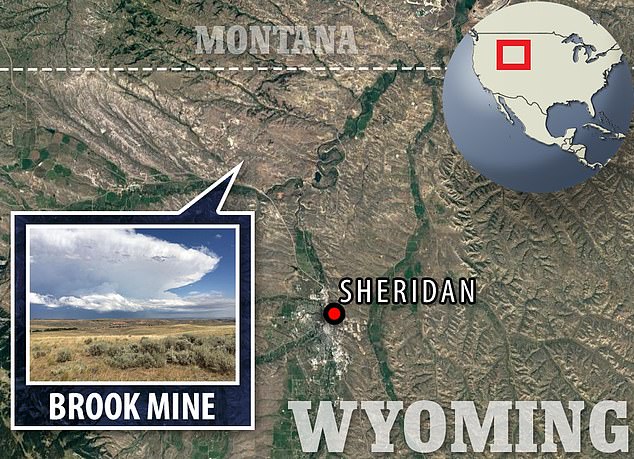

Randall Atkins, the CEO of Ramaco Rescources, bought the Brook Mine in Sheridan 12 years ago, but it wasn’t until years later that researchers checked whether the ground contained elements used for semiconductors, rockets and solar cells.

He was shocked to discover that his mine may contain the largest rare earth deposit in the United States – and that the materials may be worth 18,500 times what he paid for the land. The last American mine containing such rare materials was found in 1952.

Atkins’ 6,000-acre property in the Powder River Basin has tested positive for gallium and germanium, with estimates showing that just a quarter of the parcel could contain 1.1 million tons of oxides.

This is compared to the average annual consumption in the US of 8,300 tons.

Randall Atkins, the CEO of Ramaco Rescources, bought the Brook Mine in Sheridan 12 years ago – but it wasn’t until years later that researchers checked whether the ground contained elements used for semiconductors, rockets and solar cells.

Neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium and terbium have also been found.

Magnets made from neodymium are used in hard drives and cell phones, while praseodymium is used in high-strength alloys in aircraft engines.

Dysprosium is used to make control rods in nuclear reactors, and terbium is used in energy saving light bulbs and mercury lamps.

Its rare earths now sell for more than $1 million per tonne.

Kentucky native Atkins and his team now hope to mine the elements and process them into what’s needed for green energy – including for engines in electric vehicles and offshore wind turbines.

His $620 million company Ramaco Rescources is used to mine metallurgical coal. It was his father, Orin Atkins, who built Ashland Oil into a multinational energy conglomerate.

Before his death, he was embroiled in a slew of federal issues and pleaded guilty to fraud and conspiracy charges.

The younger Atkins told WSJ, “I look back at him with love and admiration. If I could build something that was even remotely as successful as he was during his tenure, I would be very happy.”

His $620 million company Ramaco Rescources is used to mine metallurgical coal. It was his father, Orin Atkins, who built Ashland Oil into a multinational energy conglomerate

Pictured: Ramaco Carbon iCam factory in Sheridan, Wyoming

‘What we do here is fun for the younger people. It is new, groundbreaking science and technology.

“Rare earth deposits open up a completely different horizon for this community.”

Atkins bought his lucrative mine from Brink’s, a company that was withdrawing from the coal business.

His discovery comes at a point that could be crucial for the US. As it stands, China controls most of the world’s rare earth refining and has recently restricted exports of some minerals.

As a result, China has become the dominant producer and price setter in the sector.

China controls 95 percent of the production and supply of rare earth metals, integral to the production of magnets for electric vehicles and wind farms, and this monopoly has allowed China to dictate prices and cause unrest among end users through export controls.

Rare earths, a group of 17 elements, received renewed attention after Beijing last month announced export licensing requirements for some graphite products from December to protect national security, citing national security concerns.