‘Vampire viruses’ are discovered in the wild for the first time in the US

- Viruses come into contact with other viruses to replicate in a host

- Scientists have found the first case of viruses clinging to the necks of helpers

- READ MORE: Chinese scientists discover EIGHT never-before-seen viruses

Scientists have observed for the first time ‘vampire viruses’: pathogens that attach to viruses to reproduce themselves.

Researchers have known in theory for decades that some viruses prey on other types of pathogens, unlike most that replicate themselves.

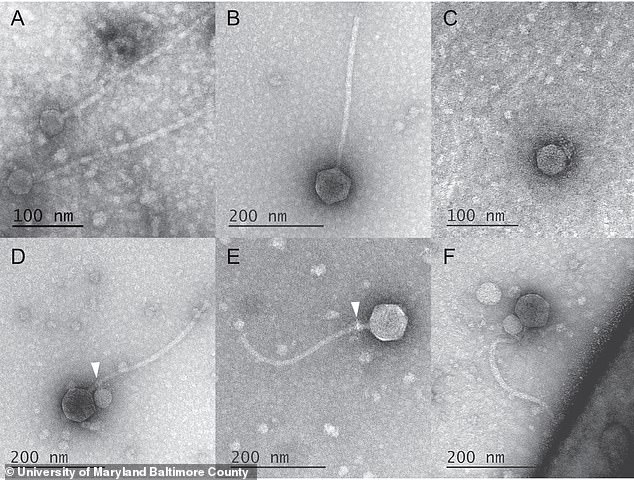

A team of researchers led by the University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC) observed a strain of bacteriophage – a type of virus that infects bacteria – clinging to the ‘neck’ of another virus – the place where the capsid is located at the tail of the virus adds. .

The first case of ‘vampire viruses’ (purple) has been observed by scientists, who discovered that some infectious agents attach themselves to the neck of another (blue) to ensure its life cycle

Biologist and lead author Tagide deCarvalho said: ‘When I saw it I thought, ‘I can’t believe this.’

‘No one has ever seen a bacteriophage – or any other virus for that matter – attach to another virus.’

The viral relationship between two pathogens is called a satellite and a helper.

The satellite is the contagious strand that depends on the helper for support throughout its life cycle.

The team studied a sample of a satellite bacteriophage (a virus that infects bacterial cells), including a species of Streptomyces bacteria (the helper) found in soil.

However, the bacteriophage usually has a gene for integration and does not attach directly to its helper.

The satellite in UMBC’s sample, named MiniFlayer by the students who isolated it, is the first known case of a satellite without a gene for integration.

An experiment showed that 80 percent (40 out of 50) of helpers had a satellite strapped to their necks

Because it cannot integrate into the host cell’s DNA, it must be near its helper (called MindFlayer) every time it enters a host cell if it is to survive.

An experiment showed that 80 percent (40 out of 50) of helpers had a satellite strapped to their necks.

Given that, even though the team didn’t directly prove this statement, “the bonding now made perfect sense,” says Ivan Erill, professor of biological sciences, “because how else are you going to guarantee that you enter the cell at the same time?”

More observations showed that MindFlayer and MiniFlayer have been evolving together for a long time.

“This satellite has been fine-tuning and optimizing its genome to be associated with the helper for at least 100 million years,” Erill said.