I grew up in Iran, when the Islamists took over we were forbidden from talking about periods and had to use old rags instead of pads or tampons. Here’s how I’m fighting back

An Australian pharmacist who grew up in Iran with limited access to pads and tampons has started her own brand of period products.

Shida Kebriti was born in Iran and had a peaceful upbringing in the ‘rich and wealthy’ country before the revolution in the mid-seventies, when the subject of periods became ‘forbidden’.

The Iranian Revolution of 1978/79, also known as the Islamic Revolution, led to the overthrow of the Western-backed monarchy and the installation of a fundamentalist Islamic regime.

According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, the new government imposed a return to conservative values - abandoning key changes, including the Family Protection Act, which gave women rights in marriage.

Islamic dress codes were enforced and speaking freely about women’s issues such as menstruation, with men in the family, was prohibited. So the girls couldn’t talk about the dwindling availability of period products.

By the time she was in her early teens, Shida said period products were hard to come by and many women would make do with scraps of material when they couldn’t afford pads or tampons.

“Sadly, these women have no choice, they don’t care about what is good or bad. They just find anything they can use,” she told FEMAIL.

“I haven’t been back in a few years, so hopefully things have changed, but I still hear that there are a lot of areas where women won’t have access to tampons and tampons.”

Sydney pharmacist Shida Kebriti (pictured) has launched her own line of period products after growing up in Iran with limited access to pads and tampons during the revolution.

The 45-year-old’s upbringing coupled with her time working in an Indigenous community less than an hour outside of Sydney, where women and girls struggled to find hygiene products, gave her a passion for eradicating period poverty.

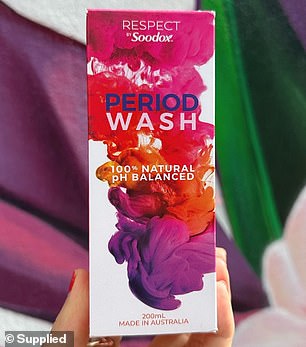

It was developed respect under its pharmaceutical brand Soodox with a line of pads, tampons and period underwear made using eco-friendly materials and free of nasty chemicals, as well as a pH-balanced wash and pain relievers.

Shida explained that since the late seventies when the Iranian revolution began, citizens have had limited access to imported products, including pillows and tampons.

“Foreign products are not available, and the market still relies on supply from local sources. So it’s very limited, but that’s not an unusual thing in the whole Middle East area,” she said.

“Across the Middle East, even in countries that don’t have sanctions, they still have limited access to this type of product.

She said women would find ways to get by without pads and tampons when they weren’t available at the pharmacy.

“A lot of women would use some kind of reusable (handmade) cotton if you had them, but then washing them could be quite difficult if you didn’t have access to washing facilities,” Shida said.

Shida said period products were hard to find and many women would make do with scraps of material when they couldn’t afford pads or tampons.

The problem women had finding suitable feminine hygiene products was made more difficult as menstruation was something no one talked about.

“You don’t talk about it with your father or your brothers, it’s a very, very taboo subject,” she said.

“It’s still a taboo subject, people don’t want to talk about it. Even some parents find it difficult to discuss this with their children.’

When Shida and her family moved to Australia when she was in her mid-teens, she saw an immediate change in attitudes towards periods.

Feminine hygiene products were available in abundance in supermarkets and pharmacies and while the subject was still a taboo, Austrians were not so shy when it came to periods.

However, in her adult life, when she became a pharmacist, Shida discovered that there were places in Australia where menstruating people had as much trouble finding tampons and tampons as women in Iran.

She did some work in an indigenous community in Wyong, which is just under an hour’s drive from Sydney.

“I couldn’t believe that just 45 minutes north of Sydney there are still Aboriginal girls who don’t have access to basic period products and don’t know how to treat it,” Shida said.

“Young girls would use things like socks or parts of a T-shirt as a pillow because they don’t have access to the right products. Sometimes they would be too embarrassed to ask because they couldn’t afford the product.’

Shida said she met many girls and women in the community who missed out on basic education during their periods.

“The concept of menstruation and bleeding was not very well explained to them. There are many reasons why, such as they live in a care home where no one is there to support them,’ she recalls.

“When they get their periods, they are not prepared. In particular, it doesn’t prepare them for the cost involved in getting the products they want.’

Shida said the pads were one of the most stolen items at the Wyong pharmacy where she worked.

“If someone is living in a care home, for example, they may be living on a very limited budget. They will be lucky to get one or two meals a day,” she said.

So for them, do they get the next meal or do they get the pillows. And I think most of the time they probably wanted to eat the next meal.’

Shida discovered there were places in Australia where menstruating people had just as much trouble finding tampons and tampons when she was working in an Indigenous community outside Sydney.

Her strong belief that things like pads and tampons should be globally accessible to all menstruating people led her to create her line.

After working in the pharmaceutical industry for so many years, she became acutely aware of the environmental damage created by the harmful chemicals contained in things like pads and tampons.

“The main factor was that I wanted products that are not plastic and very good for women’s health,” she said.

“A woman can use up to 20,000 pads during her menstrual cycle and that doesn’t even take into account pre- or post-menopausal lines, that’s just on your period.”

Shida said many big-brand period brands contain harmful substances like bleach or pesticides — and those who buy them have no idea.

“We just buy the first product available in a supermarket or pharmacy because that’s what we’re told to do – buy a tampon or a tampon. We don’t think about the product we’re using,” she said.

‘We don’t ask questions, is it good for me? Is it safe? We just buy it without reading the ingredients. Also, many people will make a decision based on price.’

Shida uses Respect by Soodox to educate people with periods about what they are putting into their bodies during that time of the month.

“Many women can have sensitivity in their private area and throughout the vagina in general. There are so many different reasons why. “You could just be allergic to the product you’re using,” she said.

“Generally what happens is we go to the doctor and they prescribe Canesten cream and then you just go through this whole cycle again.”

She created a periodic douche to keep the vagina clean without affecting the pH level and to relieve any irritation that may occur.

Shida is using her Respect by Soodox brand to educate people with periods about what they’re putting in their bodies during that time of the month.

‘When you use a face cream and it gives you an allergic reaction. You stop using. You should do the same thing, but for your private area, that’s why we developed the period wash,” she said.

There are also plastic, pesticide, bleach-free pads and tampons, and reusable underwear.

“Our products are cotton and not grown with pesticides, there is no bleach,” said Shida.

They don’t have chemicals in them, chemicals that are then put into your body, say four or five times a day for a week every month.

Shida wants to encourage menstruating Australians not to be shy when it comes to talking about their periods to break the stigma and help women not only understand their bodies better, but not hesitate to talk or ask for help when something is wrong.

“Everyone faces hormonal changes and everyone reacts differently. You talk to some women and they’ve never experienced any PMS and you talk to some others and they go through it really badly,” she said.

You should discuss this with your parents, partner or friends. They should be aware of your symptoms and how you are affected.’

That way if you are reacting or overreacting or feeling upset, they can support you in the right way. I believe this thread surrounds the conversation around mental health.’

(tagsTranslate)daily mail(s)femail(s)women’s health(s)Australia(s)Iran(s)Sydney