Exercise in a pill: Scientists develop weight-loss drug that tricks muscles into thinking they’re working hard

It sounds too good to be true, but if a new study proves anything, the future of exercise could involve taking a pill and sitting on the couch.

Researchers from Missouri and Florida have developed an injection that tricks the muscles into thinking they are working harder than they really are and stimulates metabolism.

The new drug – so far only proven in mice – targets proteins in the body’s DNA that turn on genes that determine how the body uses energy, allowing it to burn calories without any physical effort.

Rodents given the drug for a month weighed less than rodents not given the drug, despite eating the same amount of food. They also had lower cholesterol levels and burned more fat at rest.

The drug has not been tested on humans, but trials in mice are encouraging. The researchers in Florida and Missouri plan to reformat the treatment in pill form if human trials are conducted

The experimental treatment is in its early stages and still needs to be tested in other animals and then in humans, which would take years.

The potential breakthrough is known as an “exercise mimetic,” which tricks the muscles into treating increased energy burn as exercise.

The new drug is called SLU-PP-332.

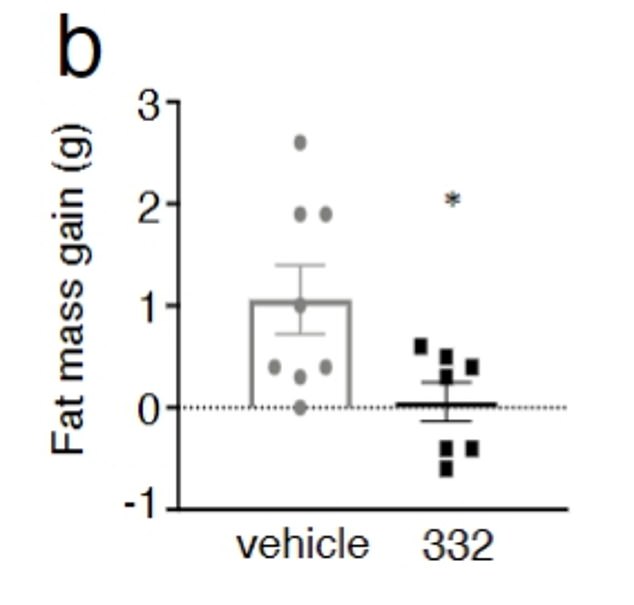

In addition to reducing fat mass even when mice were kept on a high-fat diet, the injectable also prevented mice from gaining additional weight over a 28-day period.

It also helped stabilize blood sugar levels.

Dr. Thomas Burris, professor of pharmacy at the University of Florida, said: ‘If you treat mice with the drug, you can see that their entire body metabolism switches to using fatty acids, which is very similar to what humans use when they are fasting. or sports. And the animals start to lose weight.’

They first tested their drug in a group of mice that became obese because they were fed a high-fat diet. The mice administered SLU-PP-332 for 28 days ultimately weighed 12 percent less than placebo-treated mice.

And during that time they had only gained half a gram of fat mass.

Meanwhile, the mice that received a placebo injection had gained about five grams of fat mass after that one-month period.

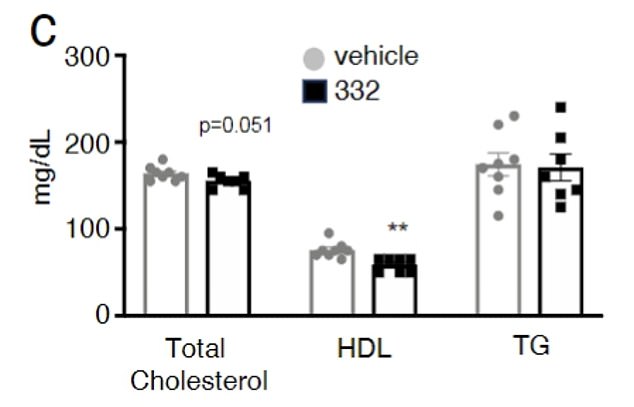

In addition to helping drug-treated mice maintain a lower amount of body fat, researchers also found that they had lower levels of cholesterol and triglycerides, a type of fat cells in the bloodstream that are stored in adipose tissue.

Elevated levels of both are usually indicators of an unhealthy diet consisting of saturated fats and trans fats, as well as sugary foods and drinks. Obesity is strongly associated with both.

Researchers also tested their drug in mice that were initially obese, and not just in mice fed the high-fat diet.

The table shows the results of a 28 day dosing schedule. Mice fed a high-fat diet for a month while receiving the new drug gained less than a gram of fat mass (the information on the right), while untreated mice gained about five grams (shown on the left)

Mice that received the injectable (indicated in dark blue) had lower total cholesterol and lower triglycerides than placebo recipients (in gray). The differences were small, but still statistically significant

Three-month-old obese mice were fed a normal diet and given the drug or a placebo for 12 days.

Those mice showed a reduced amount of body fat, also called adipose tissue, even while still eating the same amount of food.

They also found that the mice’s livers weighed less after treatment.

A heavy liver is an indication that excess fat has settled in the liver cells, which can lead to potentially serious conditions such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, which is estimated to affect about 100 million Americans.

Dr. Burris said, “This compound essentially tells skeletal muscle to make the same changes you see during endurance training.

“They use more energy just by living.”

The drug works by activating estrogen-related receptors on DNA sequences, where they play a crucial role in regulating energy expenditure.

The same team of researchers from the University of Florida, Washington University in St. Louis and St. Louis University had previously shown in a mouse trial that their drug increased endurance in mice, which were able to run 70 percent longer and 45 percent further compared to other mice. for those who received a placebo.

When certain genes need to be turned on, such as genes related to the function of breaking down fatty acids for energy, ERRs bind to DNA. Once these genes are expressed, they increase the body’s ability to burn fat.

This isn’t the first exercise-mimicking drug to be tested, but it follows groundbreaking obesity treatments to hit the market, including Wegovy and Ozempic, which were first developed to treat diabetes.

The next step will be to test the injectable in more animal models before moving on to human subjects. They also plan to transform their drug from an injectable drug to an easy-to-take pill, although that is still a long way off.

The team’s findings have been published in the Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics.