Scientists discover over 250 fossilised dinosaur eggs – suggesting they nested together like birds

>

A hatchery containing 256 fossilised dinosaur eggs has been discovered in India, suggesting the beasts nested together, just like modern birds.

Researchers in New Delhi found 92 nesting sites that once belonged to titanosaurs – a family of long-necked dinosaurs that included some of the largest to ever exist.

Covering about 620 miles (1,000 km) from east to west, the dinosaur hatchery is also one of the largest known to man, and reveals new insight into the massive species.

For example, the fact that the clutches are in such close proximity suggests that parents didn’t hang around to watch their newborns hatch, according to the experts.

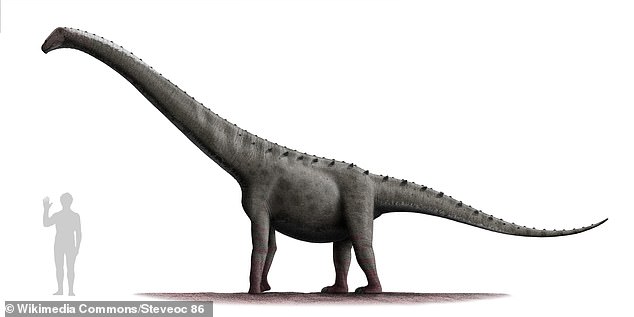

Researchers in New Delhi found 92 nesting sites that once belonged to titanosaurs – a family of long-necked dinosaurs that included some of the largest to ever exist

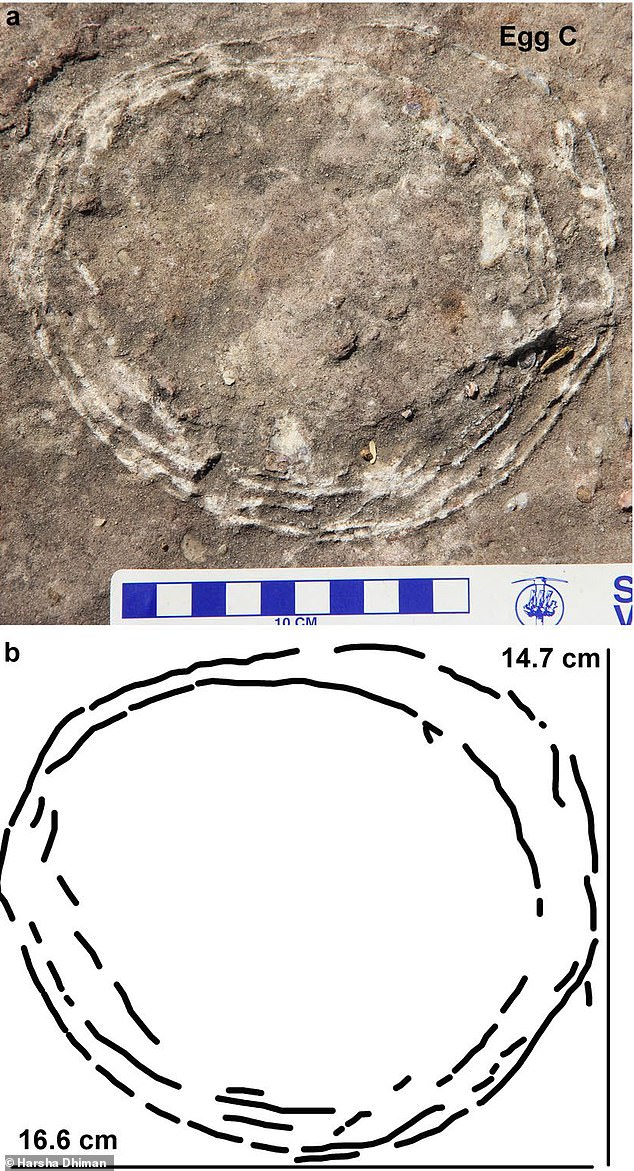

Photos of eggs and egg outlines. A: Completely unhatched egg. B: Outline of an egg thought to be unhatched. C: Compressed egg with hatching window indicated by an arrow, and egg shell fragments indicated with circles. D: Egg. E: Deformed egg showing surfaces slipping past each other

That is because there would be no room for them to do so and, if they did, the palaeontologists would have noticed more fossilised broken eggs.

Additionally, there are not many fossil records of juvenile bones in the region, suggesting the babies left the nest soon after hatching.

The hatchery is part of the Lameta Formation – a geological formation in the Narmada Valley that hosts many fossilised dinosaur eggs and skeletons from the Late Cretaceous Period.

The researchers identified eggs that came from six different titanosaur species – more than has been reported through skeletal fossils in the area so far.

This suggests that the Indian sub-continent saw a greater diversity of dinosaurs than previously thought.

Harsha Dhiman, the study’s lead author, said: ‘Our research has revealed the presence of an extensive hatchery of titanosaur sauropod dinosaurs in the study area and offers new insights into the conditions of nest preservation and reproductive strategies of titanosaur sauropod dinosaurs just before they went extinct.’

Titanosaurs were the last great family of sauropod dinosaurs before the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event, about 65 million years ago.

Sauropods were a dinosaur subgroup characterised by their four legs, long neck and tail, small head and herbivorous diet.

However, the titanosaurs’ bodies were stockier and their limbs produced a wider stance than other sauropods.

Titanosaur fossils have been found on all continents except Antarctica and include some 40 species.

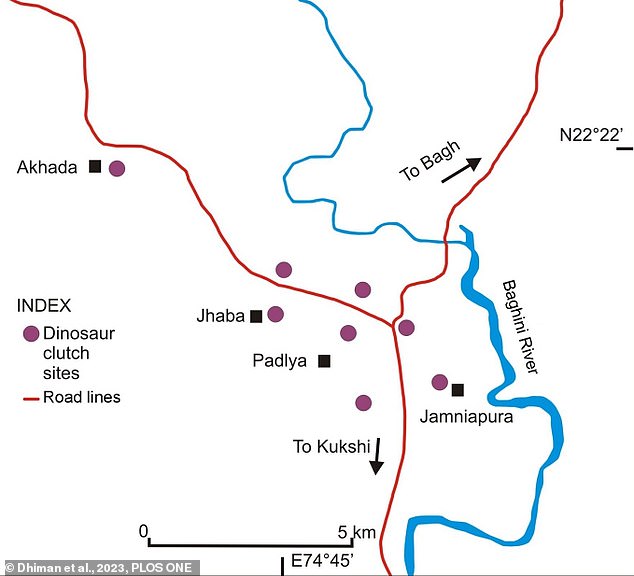

The hatchery is part of the Lameta Formation – a geological formation in the Narmada Valley that hosts many fossilised dinosaur eggs and skeletons from the Late Cretaceous Period. Pictured: Map of the study area displaying the location of investigated dinosaur clutches

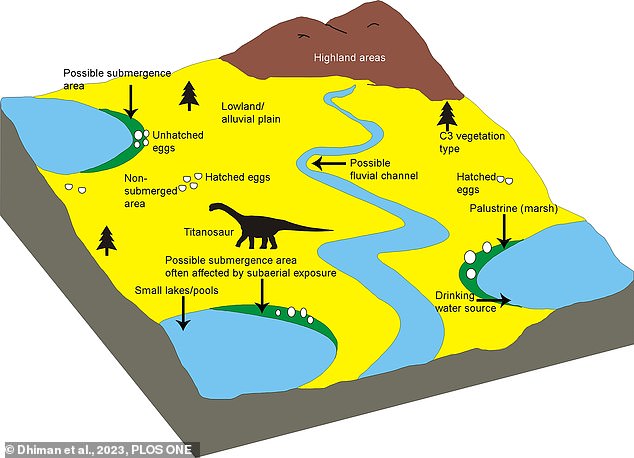

Diagram showing what researchers believe was the hatchery environment. It is thought that some of the egg clutches were laid close to the banks of the lakes and ponds, and these were frequently submerged underwater. This led to them being buried in sediment and prevented them from hatching. Clutches further from the bodies of water could hatch and hence showed more broken eggshells

Titanosaurs were the last great family of sauropod dinosaurs before the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event, about 65 million years ago. Sauropods were a dinosaur subgroup characterised by their four legs, long neck and tail, small head and herbivorous diet

Only a limited amount of information about the reproductive habits of dinosaurs can be gleaned from their remains, as their reproductive organs don’t fossilise.

However, researchers could infer a spectacular amount about titanosaur habits from the hatchery, which has been published today in PLOS One.

Some of the eggs that were discovered tightly packed together had very similar diameters, suggesting they had been buried with their surfaces touching.

The researchers believe that titanosaurs dug shallow pits for their eggs like modern crocodiles do.

They also found the first ever dinosaur ‘egg-in-egg’, indicating a creature had a segmented uterus and laid its eggs sequentially like modern birds.

An egg-in-egg occurs when an egg is pushed back into the mother’s reproductive system and becomes embedded with another newly forming egg.

It suggests that dinosaurs had a reproductive biology more similar to that of birds and crocodiles than turtles and lizards, as previously assumed.

They also found the first ever dinosaur ‘egg-in-egg’ (pictured), indicating they had a segmented uterus and laid their eggs sequentially like modern birds

The discovery of all the clutches in such close proximity also indicates that the titanosaurs formed breeding colonies that came together to nest.

This behaviour is ‘indicated by extensive clutches and morphologically similar eggs’, as well as thestratigraphic position of the Lameta Formation.

The type of rock that held the eggs led the researchers to believe that some of the clutches were laid close to the banks of the lakes and ponds.

These were frequently submerged underwater, leading to them being buried in sediment that prevented them from hatching.

Clutches further from the bodies of water could hatch, and hence these had more fossilised eggshell fragments.

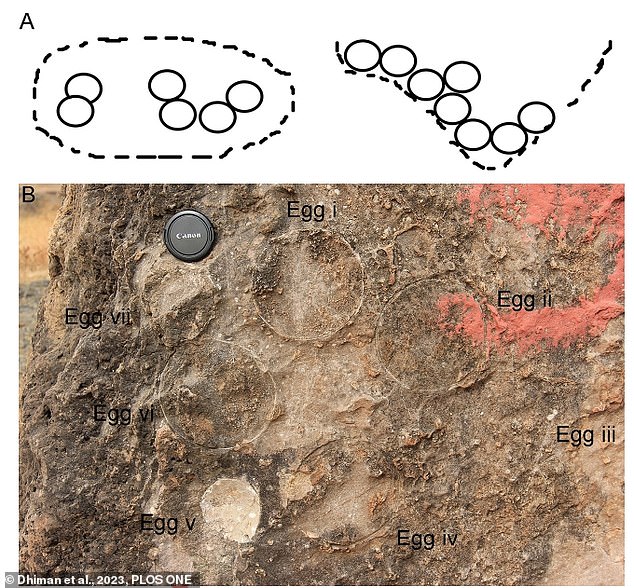

The discovery of all the clutches in such close proximity also indicates that the titanosaurs formed breeding colonies that came together to nest. Pictured: Circular dinosaur egg clutch

The type of rock that held the eggs led the researchers to believe that some of the clutches were laid close to the banks of the lakes and ponds. Pictured: Preserved broken egg fragments