Is NHS 111 fuelling dire emergency care crisis?

>

NHS 111 might be exacerbating the dire emergency care situation, paramedics and patients have warned.

Brits have been urged to use the free service this winter in an effort to alleviate the extreme demand on overwhelmed ambulance services and A&Es.

The unprecedented crisis has left ambulances taking longer than ever to respond to 999 calls and caused devastating casualty delays with 1,800 patients a day waiting more than 12 hours to be treated.

But staff and patients believe the 111 service, which acts as a basic triaging system, is unnecessarily sending out ambulances and directing patients to A&E for illnesses that are minor and not in need of urgent care.

The graph shows the number of ambulances sent out by NHS 111 each month (green bars) and the number of calls answered by the service (red line). Staff and patients say the 111 service is unnecessarily sending out ambulances for illnesses that are minor and not in need of urgent care

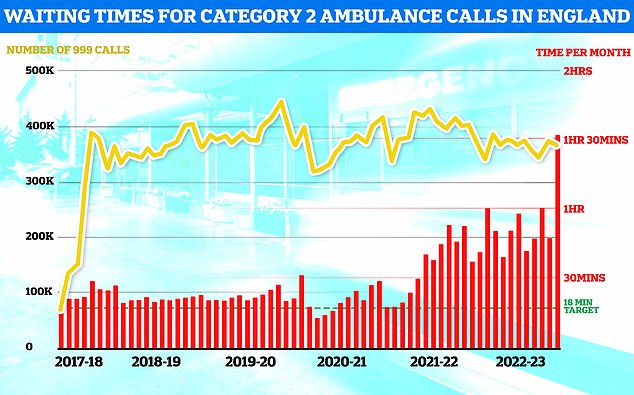

NHS ambulance data for December shows that 999 callers classed as category two — which includes heart attacks, strokes, burns and epilepsy — waited 1 hour, 32 minutes and 54 seconds, on average, for paramedics to arrive (shown in red bar). This is five-times longer than the 18 minute target (shown in green line). This is despite category 2 cases falling slightly to 368,042 (shown in yellow bar)

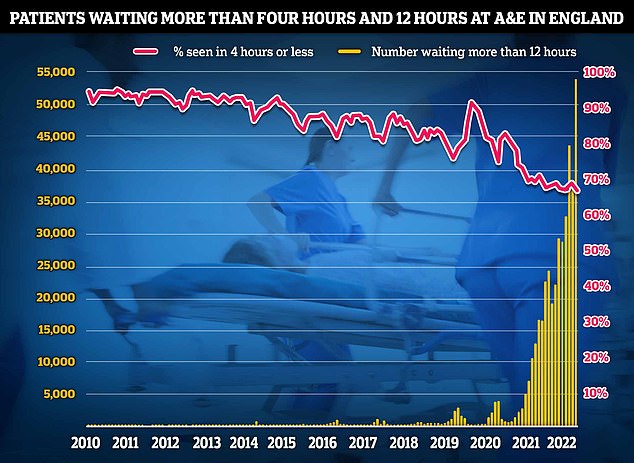

NHS A&E data for December shows that a record 54,532 people seeking emergency care were forced to wait at least 12 hours (yellow bar). Meanwhile, just 65 per cent of A&E attendees were seen within four hours (red line) — the NHS target

When ambulances are sent to non-urgent patients, fewer are available to respond to the most time-sensitive 111 and 999 calls.

It also, as a knock-on effect, clogs up A&E units, if patients are sent straight there.

Dr Adrian Boyle, president of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, previously warned that the 111 service uses algorithms that are ‘too risk averse’ and more likely to advise people to seek NHS care than manage their own illness.

Paramedics have complained that they have been sent to 111 callers with chest pain — a telltale sign of a heart attack which is a category two emergency, meaning 999 crews should arrive within 18 minutes — but in reality just have a nasty cough.

One anonymous Twitter account called simply ‘Frontline NHS Paramedic’ described the system as being ‘highly inappropriate’.

They said: ‘The 111 service needs taking away from being able to code a 999 ambulance.

‘Their triage system does not work at all! It is highly inappropriate!’

Another account, for a podcast called ‘Medic in the Middle’, hosted by paramedic Tom Alderson, said: ‘Patient calls GP practice — the practice advise patient to call 111, 111 send ambulance, ambulance call GP who calls patient.

‘We experience this all too often.’

One emergency medic in the West Midlands, speaking anonymously to MailOnline, said that paramedics find the NHS 111 service ‘tasking’.

They blamed the surge in NHS demand, which is increasing pressure ‘in all areas’.

NHS data shows that around 116,000 111 callers in England were sent ambulances in December — up by a fifth in a month and the highest logged since July.

The figure equates to 7.4 per cent of answered calls being sent an ambulance. It has been trending upwards since August.

However, it is down from the December 2019 peak, when 14.5 per cent of answered calls were sent 999 crews.

And it comes as demand for the service — which also offers advice to patients who complete a questionnaire online — surged, with 1.6m calls answered in December, up from 1.4m one month earlier.

As a whole, it marked the busiest month for the 111 service, which operates 24-hours a day alongside the 999 service, in nearly 18 months.

Andrea Newton, a podcast host in the North West, told MailOnline that her mother had a ‘chesty cough’ last month and was advised by a pharmacist to call 111.

The service recommended an ambulance as she was struggling to catch her breath due to a chronic lung condition. She turned it down, and only ended up requiring antibiotics for a chest infection, rather than emergency care.

Ms Newton said if her mother had followed 111 advice, she could have endured a 56-hour wait in A&E — which her father faced last year — where she would have been ‘cold (and) surrounded by hundreds of sick folk’.

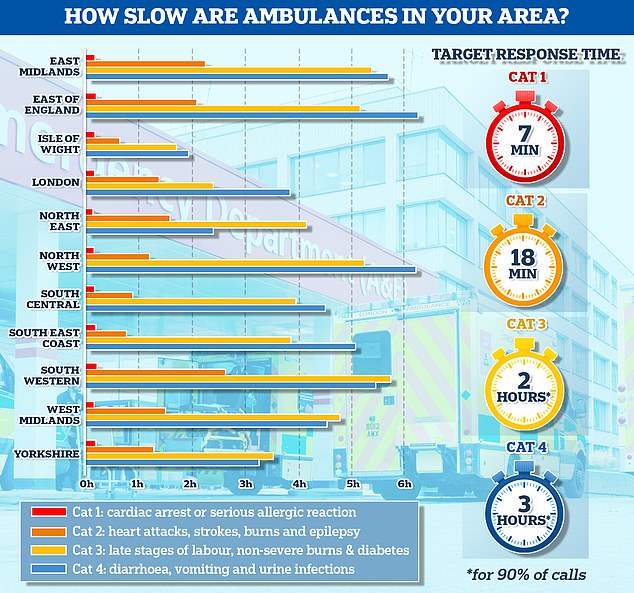

The graph shows the average response times for each category of 999 calls across 11 parts of England. The South West logged the slowest response time for both category one and category two calls, taking 13 minutes and 11 seconds and 2 hours and 29 minutes on average, respectively

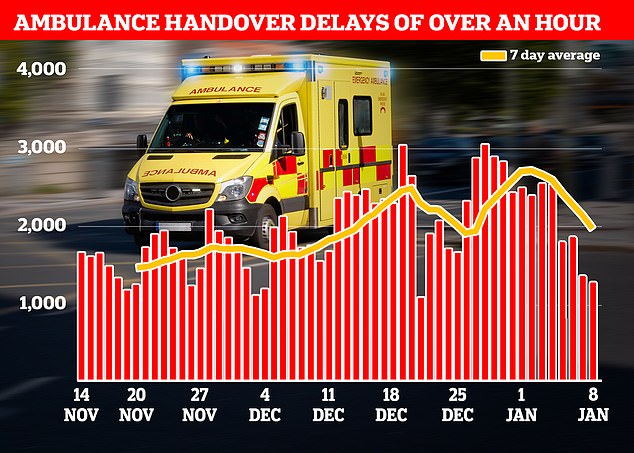

NHS data shows that in the week to January 8, 13,564 ambulances queued for more than one hour outside of hospitals (shown in red bars), down 28 per cent from 18,720 one week earlier

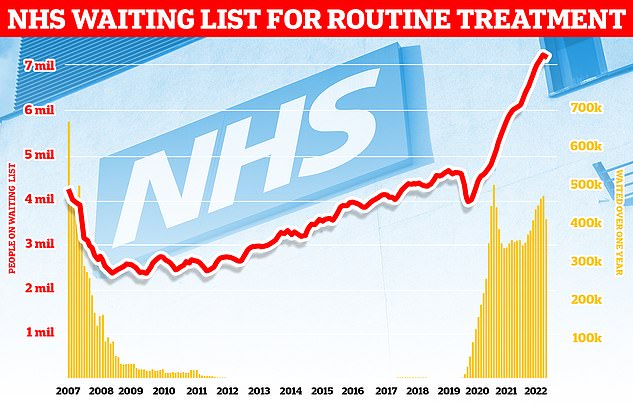

Around 7.2million patients in England were stuck in the backlog in November (red line)— or one in eight people. More than 400,000 have queued for at least one year (yellow bars)

She claimed the NHS advice is ‘mad’ as ‘all roads point to A&E regardless, hence the carnage there’.

Joel Morris, a writer, tweeted that a medical scare in his family over the festive period showed there was ‘clearly a bottleneck’ in getting help.

He said 111 has become the ‘entry point rather than a GP’, which has led call handlers to follow ‘flowcharts that always fail safe and end up with an unnecessary ambulance or A&E visit’.

A 2020 study, published in the Journal of Paramedic Practice, found NHS 111 places a burden on ambulances by generating inappropriate referrals.

These include sending 999 crews to patients who had been suffering chest pain for six months, scratched their knee and someone who had ‘drunk a glass of water too quickly and… was unable to burp’ — none of which are emergencies.

One paramedic told researchers that the ambulance service is ‘bearing the brunt’ of 111 call handlers using them as a ‘fall-back option’.

Call handlers undergo a four-week training course by 111 health advisors, after which they can answer 111 calls, assess patients’ medical needs and direct callers to the most appropriate service — including referring patients to A&E and dispatching ambulances.

A separate report, published in BMJ Open, found ambulance incidents increased by around three per cent the first year that the 111 was trialled.

The study authors said the hike was due to call handlers erring on the side of caution.

111 has previously come under fire for its performance. Latest data shows only one in five calls were picked up within one minute last month, while four in 10 calls were abandoned.

But rather than being overly-cautious, it has also previously been told to change its protocols following deaths when 111 calls were incorrectly considered non-urgent.

However, the NHS insists the decade-old service that was set up to ease pressure on emergency care by assessing symptoms and directing patients to the most suitable service, actually eases pressure on the health service.

Health Secretary Steve Barclay hailed the ‘vital’ NHS 111 service ahead of winter, saying it can ‘offer patients the right care as quickly and conveniently as possible’, which reduces pressure on A&E.

Along with dispatching ambulances and pointing people to A&E, it can also arrange for a nurse to call a patient back, or advise ill Brits to go to a pharmacy.

Latest data, based on patient survey responses between April and September 2022, shows that one in five callers would have contacted A&E or their GP practice if the 111 service had not been available, while one in 10 would have phoned 999.

An NHS spokesperson said: ‘NHS 111 uses a system of triage which has been developed with and agreed by clinicians and royal colleges – it is designed to ensure people get the appropriate care for their situation based on the answers to their questions at the time of their call.

‘As ever, people who need care should continue to come forward, using NHS 111 online in the first instance and 999 if it is life threatening.’

Health chiefs have urged unwell Brits to continue using the NHS as they usually would, despite current pressures.

This includes calling 999 in response to signs of a heart attack, stroke or breathing difficulties, and call 111 if they need medical help straight away.

It comes amid record demand that has seen emergency care performance stoop to record lows.

NHS data showed it took 999 crews nearly 93 minutes, on average, to respond to category 2 calls in England last month. It trumps the worst-ever month for such calls by half-an-hour.

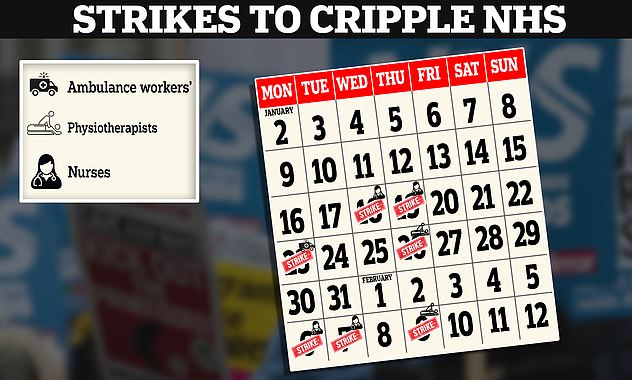

The Royal College of Nursing will hold its strikes over pay on January 18 and 19, as well as February 6 and 7. It joins Unison in five ambulance services on January 23. The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy will also stage strike action on January 26 and February 9

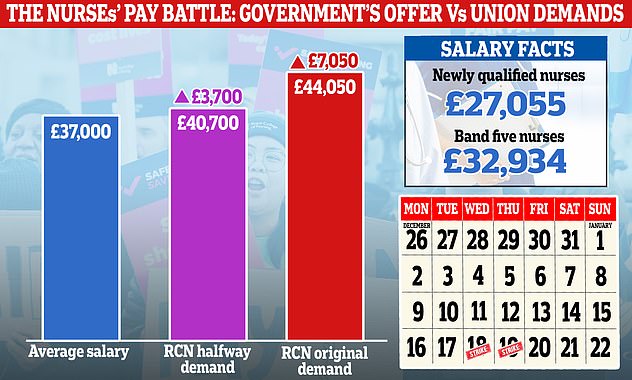

The row is over pay and working conditions, with the RCN demanding a pay rise 5 per cent above RPI inflation — equivalent to a 19 per cent boost (red bar). However, it has consistently indicated that it would accept a lower offer. A 19 per cent rise would see the average nurses’ salary rise from £37,000 to £44,050, while a 10 per cent rise would see it increase to £40,700 (purple bar)

Royal College of Nursing (RCN) General Secretary Pat Cullen, centre, joined members of the RCN on the picket line outside the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle on December 20, 2022

Response times for the most urgent calls — for people with life-threatening illnesses or injuries, such as cardiac arrest sufferers — also soared to a record high of nearly 11 minutes, on average.

A&Es were also battered last month. Nearly 1,800 patients attending casualty had to wait at least 12 hours to be treated each day in December. Only two-thirds were seen within four hours — the worst performance logged in records going back more than a decade.

Health chiefs blame a lack of space in hospitals.

Nine in 10 NHS hospital beds were occupied throughout December, including record numbers taken up by respiratory illnesses amid the ‘twindemic’ of Covid and flu.

And around 14,000 per day in the week to January 8 were taken up patients who were medically fit for discharge — known as bed-blockers.

This gives medics little space to take in fresh patients from A&E or ambulances and has a knock-on effect on paramedic response times.

The figures take into account the situation in emergency care in December, which saw nurses strike for two days and ambulance staff strike for one.

Another strike among ambulance staff took place last week and another is planned for later this month. The effects of this action won’t be made clear until next month’s performance update.

It comes as NHS care is set to be disrupted this week due to the nurses’ strike at 55 NHS trusts in England, which will see the medics work Christmas Day-style rotas in adult A&E and urgent care.

The health service will run a bank holiday-style service in many areas.

But the Royal College of Nursing (RCN), which is coordinating the action, has agreed to staff chemotherapy, emergency cancer services, dialysis, critical care units, neonatal and paediatric intensive care.

Some areas of mental health and learning disability and autism services are also exempt, while trusts will be told they can request staffing for specific clinical needs.

The RCN — which is seeking a inflation-busting 19.2 per cent pay rise for nurses — yesterday confirmed nurses will also strike on February 6 and 7.

But the February action will cover 73 trusts. Some 12 health boards and organisations in Wales will also take part in the two consecutive days of strikes.

Health leaders described the additional strike dates as ‘very worrying’ and warned they will likely have an ‘even greater impact’ than previous walkouts, which were already ‘disruptive’.

The December action saw thousands of hospital appointments and operations cancelled.

The RCN said it will not take action in Northern Ireland next month, while in Scotland strike action remains paused as negotiations continue.

The union said it has repeatedly urged ministers to open talks on NHS pay and discuss the pay award for the current financial year, 2022/23.

Its decision to strike on February 6 is designed to coincide with the 10th anniversary of the Robert Francis inquiry into Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust, which highlighted the impact of nurse shortages on patient care and excess deaths.

The inquiry uncovered the neglect of hundreds of patients at Stafford Hospital between 2005 and 2009, with accounts of some elderly people being left lying in their own urine, unable to eat, drink or take essential medication.

In a letter to the Health Secretary last week, Mr Francis and the Patient Association’s chief executive, Rachel Power, described the current stress on the NHS and excess death levels as ‘Mid Staffs playing out on a national level, if not worse’.

Ambulance staff and physiotherapists are also due to take further industrial action in a row over pay and junior doctors are being balloted on industrial action.

RCN chief executive Pat Cullen said of the latest strike announcement: ‘It is with a heavy heart that nursing staff are striking this week and again in three weeks.

‘Rather than negotiate, (Prime Minister) Rishi Sunak has chosen strike action again.

‘We are doing this in a desperate bid to get him and ministers to rescue the NHS.

‘The only credible solution is to address the tens of thousands of unfilled jobs – patient care is suffering like never before.

‘My olive branch to Government – asking them to meet me halfway and begin negotiations – is still there. They should grab it.’

Last Wednesday, Health Secretary Mr Barclay said he does not ‘think it is right’ to ‘retrospectively’ go back to April when it comes to reviewing the current pay award for NHS staff.

It came after reports he is considering backdating any 2023/24 pay rise, due to be finalised in the spring, to this month in order to boost the current year’s settlement offer.

The RCN has been calling for a pay rise at 5 per cent above inflation, though it has said it will accept a lower offer.

Inflation was running at 7.5 per cent when it submitted the 5 per cent figure to the independent pay review body in March.

But inflation has since soared, with RPI standing at 14 per cent in November.