Ocean temperatures hit a record high in 2022, data shows

>

Ocean temperatures in 2022 were ‘the hottest in the historical record’, breaking a record already set in 2021, a new study reveals.

An international team of researchers say Earth’s oceans received an additional 10 Zetta joules of heat – or 10 followed by 21 zeroes – last year.

This is enough to boil 700 million 1.5 litre kettles every second for a year, or 100 times the world’s electricity generation in a year.

The experts say the findings show how the world’s oceans have been ‘profoundly affected’ by the emission of greenhouse gases from human activities.

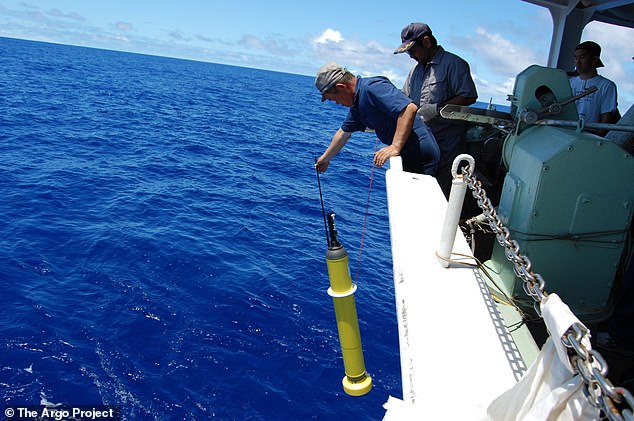

In 2022, Earth’s oceans received an additional 10 Zetta joules of heat – or 10 followed by 21 zeroes, the new study says. Results were based on datasets that compile ocean temperature and salinity using instruments such as Argo profiles (free-drifting robotic floats that move with ocean currents, pictured)

The new study, published on Wednesday, presents oceanic observations from 24 scientists across 16 institutes worldwide.

‘The oceans are absorbing most of the heating from human carbon emissions,’ said study author Professor Michael Mann at the University of Pennsylvania.

‘Until we reach net zero emissions, that heating will continue, and we’ll continue to break ocean heat content records, as we did this year.

‘Better awareness and understanding of the oceans are a basis for the actions to combat climate change.’

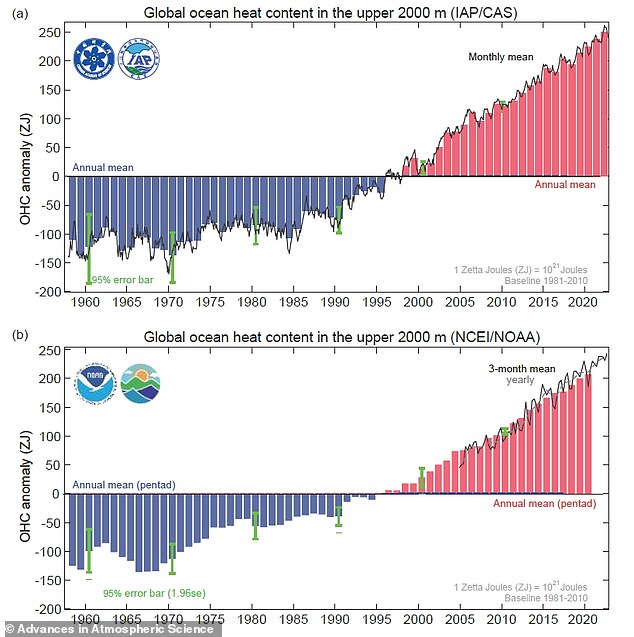

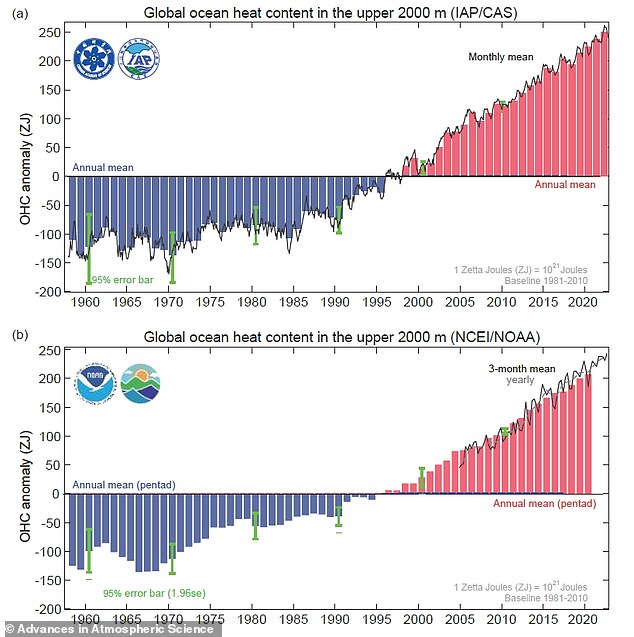

The research team used two international datasets – one from China’s Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP), and the other from US government agency the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) – which both analyse observations of ocean heat content (OHC) and their impact dating from the late 1950s.

OHC is a term for the energy absorbed by the ocean, where it is stored for indefinite time periods as internal energy.

Instruments used to collect OHC data over time include expendable bathythermographs (probes dropped from a ship that measure temperature as they fall through the water) and Argo profiles (free-drifting robotic floats that move with ocean currents).

Graphs show ocean heat content (OHC) from 1958 through 2022 according to datasets from China’s Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP) (a) and the US National Centers for Environmental Information (b)

According to the data, heat contained in the top 2,000 metres (6,560 feet) of the ocean was 10 ZJ.

The average depth of the world’s ocean is about 3,688 metres, so the upper 2,000 metres (6,560 feet) constitutes the majority of the ocean’s depth.

However, the deep ocean, below 2,000 metres, is thought to be impacted by climate change too, so 10ZJ is likely a conservative estimate for the whole of the ocean.

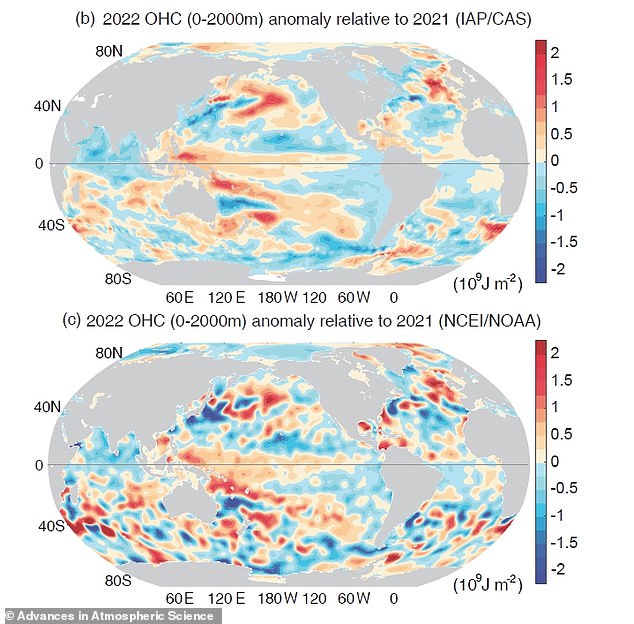

Researchers found four ocean basins in particular (the North Pacific, North Atlantic, the Mediterranean Sea and southern oceans) recorded their highest OHC since the 1950s.

The team also collected data on ocean salinity (how much salt is in the water), which tends to increase due to climate change.

Excess heat causes evaporation, which takes low-salt freshwater from the ocean into the atmosphere – increasing the ocean salinity over time.

What’s more, salinity levels, along with temperature, directly affect seawater density (salty water is denser than freshwater) and therefore the circulation of ocean currents from the tropics to the poles.

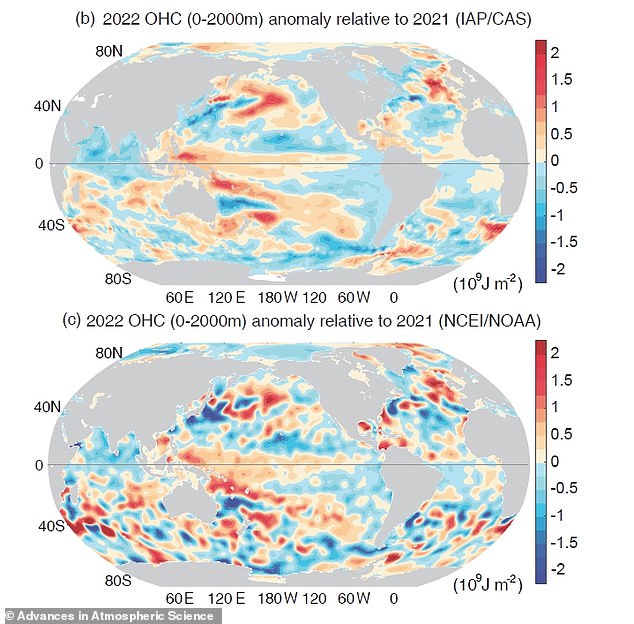

Maps show the difference in annual mean OHC in the upper 2,000m between 2022 and 2021 based on data from the Chinese database (top) and the US database (bottom)

Researchers found the ‘salinity contrast index’ – the difference between the salinity averaged over high-salinity and low-salinity regions – reached its highest level on record in 2022.

‘Global warming continues and is manifested in record ocean heat, and also in continued extremes of salinity,’ said study author Lijing Cheng at the Institute of Atmospheric Physics.

‘The latter highlight that salty areas get saltier, and fresh areas get fresher and so there is a continuing increase in intensity of the hydrological cycle.’

Unfortunately, increases in ocean temperature reduce dissolved oxygen in the ocean because oxygen is less soluble in warmer water.

This affects sea life, particular corals and other temperature-sensitive marine organisms.

The surging temperatures are sparking marine heatwaves, with one notorious example in the North Pacific dubbed ‘The Blob’.

The experts say heat in the world’s oceans have been ‘profoundly affected’ by the emission of greenhouse gasses from human activities (file photo)

The Blob – a mass of warm water in the north Pacific Ocean – has decimated marine life ranging from plankton to whales and killed 100 million cod, scientists believe.

Rising ocean temperatures also increase the quantity of atmospheric moisture, and change the patterns of precipitation and temperature globally, the authors say.

The study, which is titled ‘Another year of record heat for the oceans’, has been published today in Advances in Atmospheric Science.

Read similar stories here…

Last year was Earth’s fifth hottest on record, data shows

Amount of microplastics found on the seafloor has TRIPLED in 20 years

Fish find it harder to identify competitors after mass coral bleaching