Scientists warn popular fruit could be wiped out by fungus rapidly-spreading worldwide

Scientists have warned that blueberries could be eradicated, a fungus that is spreading rapidly worldwide.

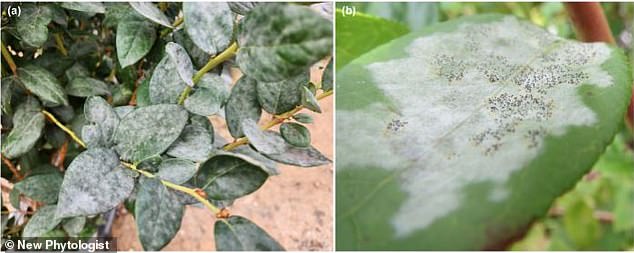

The disease is caused by two different fungal species and appears as a white powdery mildew on plants, reducing crop yields and increasing dependence on fungicides.

The team discovered that Erysiphe vaccinii has spread worldwide over the past twelve years.

One strain made its way to China, the world’s largest producer, Mexico and California, while another ended up in Morocco, Peru and Portugal.

Michael Bradshaw, an assistant professor at North Carolina State, said, “This is a difficult organism to control. If you send plant material into the world, you are probably spreading this fungus.’

The team also found that the fungus found in out-of-order blueberries reproduces exclusively asexually.

Both sexual versions of the fungus are not required for reproduction, while in the US the fungus reproduces sexually and asexually.

The study estimates that the annual blueberry industry should cost between $47 million and $530 million annually, as more than four billion pounds of blueberries are sold annually worldwide.

Scientists have warned that blueberries could be eradicated, a fungus that is spreading rapidly worldwide. The disease is caused by two different fungal species and appears as a white powdery mildew on plants, reducing crop yields and increasing dependence on fungicides.

Map showing the global presence of powdery mildew bacteria, taken from a recent University of North Carolina study showing high concentrations of the fungus in the northeastern regions of the United States

The disease is believed to have originated in the eastern US and has been largely contained there, although small outbreaks appear to have emerged in Southern California.

In addition, the study comes with a warning to the Pacific Northwest, as the rainy climate provides a perfect breeding ground for powdery mildew to infiltrate crops that until now seemed to prevent any disease in that area.

The powdery mildew covers the host plants and functions almost parasitically.

By depleting the plant of nutrients and slowing down the photosynthesis process, the fungus grows while at the same time keeping the host alive.

However, with the discovery comes hope for the ability to more easily identify the spread of the disease and thus slow it down and control it more comfortably.

Because the fungus that causes powdery mildew in blueberries can be difficult to identify, North Carolina state researchers have developed a database that can be used by scientists and farmers alike to report and review previously reported data on the disease.

“This platform allows growers to enter their data and learn what specific species is in their fields,” Bradshaw said.

‘That’s important because understanding the genetics can alert farmers about which strain they have, whether it is resistant to fungicides, how the disease spreads, and also about the virulence of certain strains.’

Powdery mildew E. Vaccinii shown on leaves of blueberry plants

Microscopic photography of isolated parts of the fungus

Although the fungus has been primarily identified in blueberry plants, the species has been found to infect wheat, hops, grape and strawberry plants.

The blueberry plant is native to the Americas and is considered one of the first edible fruit-producing plants discovered by indigenous people after the last ice age.

In addition to picking and eating fresh, Native Americans also incorporated blueberries into a variety of dishes, including soups, stews, preserves, and puddings.

However, the blueberry’s early uses extended far beyond cultural cuisine and culminated in medicinal applications in combination with roots, stems, leaves and flowers.

Known today as the highbush variety, the plant originally ranged from the Arctic plains across what is now the United States, through Mexico and into some parts of South America.

Although this information about the disease has only recently come to light, the samples analyzed in the University of North Carolina study included a specimen collected by the North American Herbarium more than 150 years ago.