Recently discovered ‘hook-headed’ creature is brutally killing animals on scenic California island

A recently discovered ‘hookhead’ parasite is brutally killing a near-threatened species on a picturesque island off the coast of California.

The Pachysentis canicola parasite was first discovered on San Miguel Island in Santa Barbara County after researchers found native animals dead or severely emaciated in 2012.

The deadly parasite lives in the intestines of its host and erodes and inflames the inside of the host until it is removed or the animal dies.

The nightmare animal now threatens a volatile population of native island foxes, which were only recently delisted from the US Endangered Species Act in 2016.

With the help of researchers, the San Miguel Island fox made a slow but successful recovery after a steep population decline in the early 2000s.

Despite the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service removing predators and other invasive species from the 9,325-acre island, researchers have again noticed a sharp decline in the fox population.

And there are clear, disturbing signs of what is to blame.

A large number of foxes that scientists examined or monitored after the discovery of Pachysentis canicola carried the parasite and showed poor body condition and low weight.

Such discoveries have “raised alarm bells about this new parasite,” said Oscar Alejandro Aleuy, a professor of biology at Florida Atlantic University. The Animal Protection Association.

A recently discovered hook-headed creature is brutally killing a near-threatened species on a picturesque island off the coast of California. Pictured: A close-up of the head of the Pachysentis canicola parasite, showing the hooks

The ‘hookhead’ parasite Pachysentis canicola was first discovered on San Miguel Island in Santa Barbara County (pictured) after researchers found native animals dead or severely emaciated in 2012.

The deadly parasite, which lives in the intestines of its host and erodes and inflames the host’s insides until its removal or death of the animal, is now threatening a volatile population of native island foxes that have only recently been delisted from the American Endangered Species Act. Pictured: The San Miguel Fox, scientifically known as Urocyon littoralis littoralis

Researchers also attribute the decline to a “severe drought” that may have exacerbated the damage caused by the parasites.

“It seems like the perfect storm,” Alejandro Aleuy said. ‘You have an island full of foxes, a severe drought and a new disease-causing parasite emerging. That could have led to a dramatic decline in foxes.”

‘It is very difficult to separate the environment and the parasite from the fox population. These are all underlying mechanisms that we need to investigate further.’

Aleuy suspects that researchers accidentally imported infected animals during the fox breeding program.

However, there is a remote possibility that the harmful parasite has always been on the island, but went unnoticed until recently.

“We can’t be 100 percent sure it’s invasive, but it’s very likely,” Alejandro Aleuy said.

So far, Pachysentis canicola has only been found on San Miguel Island and has yet to ‘cross over’ to any of the fox subspecies on the other Channel Islands – including the Santa Catalina Island fox, which remains on the U.S. list Endangered Species Act state.

Researchers, including Alejandro Aleuy, believe there are intermediate parasite hosts, but they have not yet identified which species they might be.

“Such knowledge will be important to understand how the parasite completes its life cycle on the islands,” he said.

Alejandro Aleuy also claimed that the native fox species had previously reached its ‘carrying capacity’ on the island, which may have contributed to the population decline.

“The problem is we don’t really know what the carrying capacity of the island is,” he said.

A large number of foxes that scientists examined or monitored after the discovery of Pachysentis canicola in 2012 carried the parasite and showed poor body condition and low weight. Pictured: The total number of adult parasites found in a heavily infected fox

Researchers also attribute the decline to a “severe drought” that may have exacerbated the damage caused by the parasites. In the photo: the Salinas River flowing in winter on San Miguel Island

Researchers plan to continue monitoring and further investigating the life cycle of the near-threatened animals, so wildlife managers can hopefully figure out what’s going on with more certainty.

The shocking discovery comes just days after a fly that lays flesh-eating larvae was discovered in Mexico and could pose a threat to people and wildlife in Texas.

The Texas Department of Parks and Wildlife has since issued an urgent warning to residents of the south to be on the lookout for the New World screwworm, whose Latin name, hominivorax, means “man-eater.”

On November 22, a cow with the larvae was found during an inspection check in Chiapas, near the Mexico-Guatemala border.

“As a protective measure, animal health officials are asking those along the southern border with Texas to monitor wildlife, livestock and pets for clinical signs [the insect] and immediately report potential cases,” the TPWD said in a statement.

According to the agency, the screwworm migrates ‘gradually’ north and mainly infects livestock.

However, it can affect people and wildlife, including deer and birds, TPWD said.

The parasite has not been seen in the US since 1966, after an extensive federal and state sterilization process succeeded in eradicating the fly from the United States.

Experts are concerned that it could have a devastating effect on the US economy if it reaches the US.

“It can have a huge impact, especially an economic impact, because it reduces the health and welfare of our livestock,” Jennifer Koziol, an associate professor at the Texas Tech School of Veterinary Medicine, told me. Drovers.

“We’re thinking about the loss of animal use, and certainly the wildlife populations that could be decimated by this disease.”

The Texas Department of Parks and Wildlife has issued an urgent warning to southern residents to be on the lookout for the carnivorous New World Screwworm, whose Latin name, hominivorax, means “man-eater.”

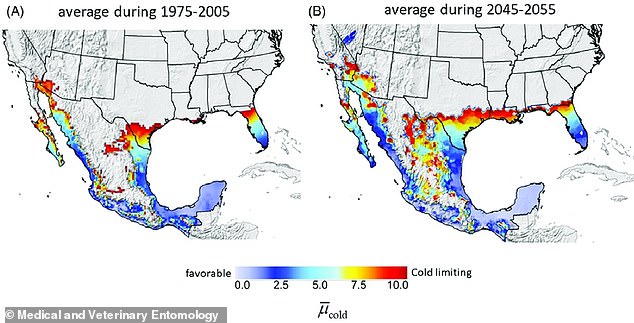

A map showing where the screwworm is currently located and how deeply it is expected to invade the United States by 2055

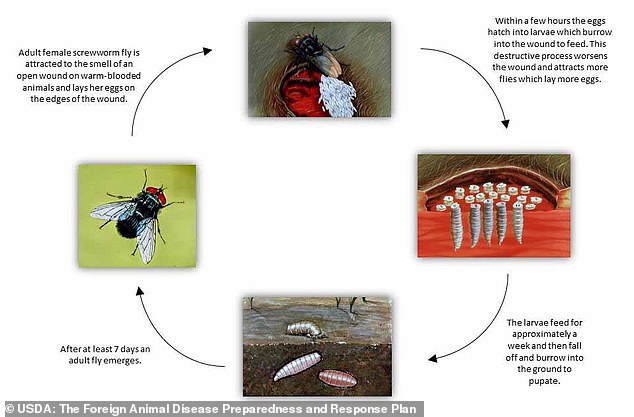

The screwworm begins its reign of terror with a female fly laying eggs in an open wound or openings. These eggs then hatch into dangerous larvae that burrow into wounds like screws

The screwworm begins its reign of terror when the female fly lays her eggs in an open wound or openings.

The female flies are attracted to the open wounds and orifices by the odors they emit. They can be as small as a tick bite, a nose or eye opening, a newborn baby’s belly button or genitals, the TPWD said.

These eggs then hatch into dangerous larvae that burrow into the wound like screws, according to the agency.

Female flies can lay up to 200 to 300 eggs at a time and up to 3,000 during her lifetime. KHO 11. Infections may also be visible on the skin.

Infections can be fatal and are often serious. The New York Times reported in 1977 that one infection could “kill a full-grown bull in ten days.”

The government agency recommends covering all open wounds, especially if traveling in affected areas such as Central or South America. It is also recommended to wear insect repellent when hunting, hiking or bird watching.