12698225 What’s your ‘ageotype’?: Scientists reveal the four ways we age biologically that matter more than how many birthdays we’ve had

Aging is an inevitable part of the human experience, but not all parts of the body age in the same way or at the same rate.

Researchers at Stanford University identified four biological aging patterns, or ageotypes, that explain why certain parts of some people’s bodies change differently than others over time.

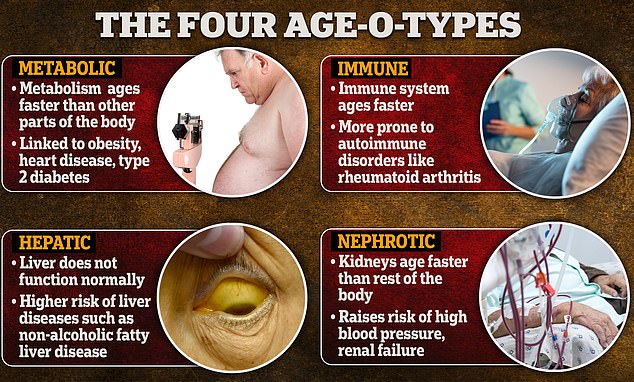

The four types relate to metabolism, the immune system, the liver and the kidneys.

A person may have a chronological age of 40 but an immune system of 45, putting him or her at greater risk of developing an autoimmune disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, while a liver ageotype is likely to have a higher risk of liver diseases such as cirrhosis .

The team of genetics experts wanted to understand why certain people are more susceptible to various aging-related conditions throughout their lives. They say this information could give people a better chance of preventing these health problems as they get older.

To determine the four classes of aging, Stanford researchers took blood, fecal, genetic material, metabolites, protein and lipid samples over the course of two years to see how people’s body systems aged.

Researchers believe that identifying age type will empower people to seek the best preventive health care for them, whether that means increasing exercise to prevent age-related metabolic disorders or limiting alcohol intake to prevent liver diseases.

Researchers at Stanford University sought to determine how individuals age over time at the molecular level in one of the few studies of its kind that followed the same subjects and the ways in which their bodies change over time.

Dr. Michael Snyder, chair of genetics at Stanford University School of Medicine and lead author of the ageotypes report, said: ‘Our study provides a much more comprehensive picture of how we age by studying a wide range of molecules and multiple samples over the years to take. of each participant.

‘We can see clear patterns at the molecular level of how individuals experience aging, and there is quite a bit of difference.’

They were able to identify four key biological pathways that could explain why some parts of people’s bodies deteriorate more quickly than others and how they can take preventative measures earlier in life.

The team followed 43 healthy men and women for two years, ranging in age from 34 to 68 years. Researchers took samples of feces, blood, genetic material, microbes, proteins and other byproducts of metabolic processes over at least five well visits and monitored the levels of biological molecules over time.

By tracking how samples changed over time, the team identified 608 molecules that could be used to predict what might contribute to age-related health problems.

A person whose ageotype is metabolic is more likely as they age to experience health problems that affect their metabolism, a finely tuned system of chemical reactions in the body that turns food into fuel for the body’s many biological processes.

A metabolic ageotype is more likely to have problems controlling blood sugar levels and is more susceptible to heart failure, insulin resistance, obesity, and type 2 diabetes later in life. Someone who is metabolically older may be more likely to become obese later in life, while at the same time he can have the immune system of a much younger, stronger person.

An immune ageotype refers to a person whose immune system ages faster than the rest of the body. Immune ageotypes accumulate more markers of inflammation throughout the body, which is a response to the body’s fight against harmful pathogens and toxins such as free radicals that enter the body.

These people may also be at greater risk for autoimmune diseases caused by the immune system’s overzealous response to the body’s cells, such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, type 1 diabetes, and multiple sclerosis.

A hepatic ageotype is one in which the liver ages faster than the rest of the body. Aging is already associated with deterioration in liver function, including reduced blood flow to the liver.

The liver is an essential organ for filtering and detoxifying blood, processing toxins such as alcohol and drugs, and hundreds of other functions crucial to sustaining life. But with a liver ageotype, their liver function will deteriorate as they age, putting them at greater risk for cirrhosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

The nephrotic ageotype refers to renal function. The kidneys remove waste from the blood to produce urine and balance the body’s fluids, sending the cleansed blood back through the body. Healthy kidneys also help control blood pressure.

The renal ageotypes are at greater risk of kidney disease later in life.

Even though people fall into one of these age-type ranges, that doesn’t mean they don’t see aging in other parts of their bodies as well.

For example, one person in the study showed signs of being a renal ageotype, but showed only minor age-related changes in other pathways. Meanwhile, another person showed signs of rapid aging in the kidney and metabolic pathways, but slower aging in the immune and liver pathways.

The Stanford researchers’ findings, published in the journal Nature Medicine, suggested that as people gain a better understanding of which biological processes are likely to break down first, they will be much more likely to improve their health by losing weight. limiting smoking and alcohol consumption and controlling their high blood pressure and glucose levels.

Dr. Snyder said, “The ageotype is more than a label; it can help individuals identify health risk factors and find the areas where they are most likely to encounter problems later.

‘Most importantly, our research shows that it is possible to change the way you age for the better. We are starting to understand how this happens with behavior, but we will need more participants and more measurements over time to fully shape it.’